With receivership looming, what could the future of Rikers look like?

/The jail complex on Rikers Island, which could soon be taken out of the city’s control and handed over to a court-appointed receiver. AP file photo by Seth Wenig

As a federal judge considers taking Rikers Island out of the city’s control and handing it to a court-appointed receiver, the Eagle is looking back at the history of the city’s troubled jail complex – which we have covered extensively since our founding in 2018 – in an effort to understand how the city arrived at this critical moment. On Friday, the Eagle looked at the lead up to the call for receivership. Today, we dive deeper into the fight to put Rikers into a receivership and what that may mean for the future of the city’s notorious jail complex.

By Jacob Kaye

Mayor Eric Adams likes to say he’s been to Rikers Island more than any other mayor in the history of the city.

It’s an unverified claim, and Adams has never given any evidence to support it – but it could very well be true.

Not only did Adams begin his career in public service as a police officer, a job that would likely put him in Rikers’ orbit, but he’s also spent much of his time in elected office focusing on law and order policies. During his mayoral tenure, he’s appeared to be particularly interested in the workings of the city’s public safety apparatus, including its jails.

Over the years, he’s made trips to Rikers Island on holidays, visiting the women’s jail facility on Thanksgiving and meeting with a group of born-again detainees on Good Friday. He brought Rev. Al Sharpton along with him during that Good Friday trip and got baptized by the minister inside the walls of the jail.

Adams has often pointed to his alleged unique familiarity with Rikers as one of the main reasons he believes the city should remain in control of the crumbling jail complex, a question federal Judge Laura Swain is expected to rule on in the coming months.

“I don't believe that Rikers is beyond repair and we want the job of repairing Rikers,” Adams said in November 2023, days after the Legal Aid Society officially asked Swain in a legal filing to strip the city of its control over Rikers and hand it over to a court-appointed authority known as a federal receiver. “We want that job.”

Despite Adams’ confidence, the city, by many measures, has been unable to repair Rikers at any point during its violent history, which spans nearly a century. Nor has it been able to truly address the horrid conditions that led to the 2015 consent judgment in the civil rights case known as Nunez v. the City of New York.

Adams is only the latest elected official to enter City Hall with a promise to fix the jail complex on Rikers Island. He may also be the last mayor for some time who actually has the power to do so.

‘Unacceptable and contemptuous’

For most of 2023, the writing was on the wall for Louis Molina.

The then-Department of Correction Commissioner had clashed not only with Swain’s court appointed federal monitor, Steve J. Martin, and with the judge herself, but he had also appeared to make enemies out of the Board of Correction, the City Council and scores of advocates who felt Molina was taking Rikers in the wrong direction.

His tenure was marked by one controversy after another.

Over two dozen people died on Rikers under Molina’s watch, a death toll that hadn’t been seen in a decade. He also sparked controversy on numerous occasions for proposing policies that appeared to roll back transparency in the already-secluded jails, including an effort to ban BOC staff from viewing live Rikers video feeds remotely.

Molina also weakened the office charged with internal investigations when he pushed out the deputy commissioner in charge of looking into the nearly 9,000 backlogged claims of unnecessary use of force incidents within the jails. He also eliminated programming meant to keep detainees out of trouble and attempted to severely roll back the amount of time those incarcerated on Rikers could spend out of their cells.

But none of his controversies appeared as impactful as the ones that unfolded over the course of 2023, his second year leading Rikers. That year, he withheld information about nearly half a dozen incidents – two of which resulted in detainees dying – from the monitor. He also opened up a secure housing unit meant to hold detainees accused of habitually committing arson without first telling the monitor, as required by the consent judgment.

“The court has repeatedly ordered the city to consult with the monitor,” Swain told Molina during a December 2023 court hearing. “Because the court has offered the department a number of opportunities to improve its cooperation with the monitoring team, [the opening of the unit] is unacceptable and, in a word, contemptuous.”

The debacle served as a seemingly fitting close to Molina’s nearly two-year tenure as commissioner, which officially came to an end the week before the hearing. Adams had “promoted” Molina to serve as the city’s first-ever assistant deputy mayor for public safety in November. Though the mayor insisted that Molina’s move had nothing to do with his performance at the DOC, the timing was suspicious.

It also didn’t appear to help with the city’s defense against receivership, as it may have been intended to.

Shortly after his promotion was announced, Swain said the move “raise[d] profound questions that demand answers about the management of the department.”

That’s when Adams decided to appoint Lynelle Maginley-Liddie to serve as the DOC’s next commissioner.

Department of Correction Commissioner Lynelle Manginley-Liddie. Photo via DOC

Maginley-Liddie, who remains the DOC’s top official, appeared to check a number of important boxes for the mayor. As an agency attorney, she had spent years working closely with the monitor and his team and was intimately familiar with the consent judgment at the heart of the Nunez case. She also presented herself as more reform-minded than her predecessor, pleasing Swain, the monitor, advocates and lawmakers in the City Council. Having spent several years serving as a deputy commissioner, Maginley-Liddie also was welcomed by correctional officers and their union, whom she had already developed a relationship with.

“In her work at the department, the monitoring team has found the commissioner to be transparent and forthright,” Martin said in a court filing after Maginley-Liddie’s appointment in December 2023.

Riding a wave of good will, Maginley-Liddie got to work. She reversed several controversial policies put in place by Molina and attempted to mend relationships with the DOC’s oversight groups.

Under Maginley-Liddie, the DOC would again notify reporters of detainee deaths. She also asked a number of nonprofits to return to Rikers to offer social services programming, which Molina had abruptly ended.

But while some progress was being made on Rikers, other indicators of violence remained stubbornly stagnant. And some got worse.

Use of force incidents remained relatively unchanged during Maginley-Liddie’s first year as commissioner, according to DOC data, but assaults on staff nearly doubled during the commissioner’s first six months in office and detainee fights increased by around 13 percent during her first year at the DOC’s helm.

“The risk of harm in the jails remains very high, often punctuated by acute spikes in violence that further intensify the concern about safety for people in custody and staff,” the monitor wrote in his most recent update on the conditions in Rikers.

There were also several troubling reports about the treatment of detainees that sparked alarm during Maginley-Liddie’s first year in office. In July, a 23-year-old detainee named Charizma Jones died of organ failure in a hospital not long after DOC officers had locked her in an isolated cell and allegedly refused doctors to treat her for two straight days. Then in October, a whistleblower told the BOC that officers were effectively putting detainees with mental illnesses in solitary confinement and blocking their access to medical care on a regular basis. Described as Rikers’ “worst-kept secret” by a public defender during a BOC hearing in the fall, the practice had alluded Maginley-Liddie, the commissioner claimed.

But whether or not Maginley-Liddie’s tenure as commissioner has thus far been a success is irrelevant, the Legal Aid Society has argued.

In their receivership filing, the Legal Aid Society said the DOC’s dysfunction, which has led to unconstitutional conditions on Rikers, was not borne from any one commissioner or mayor, but from the constant change in leadership at the top of the agency.

Since the start of the consent judgment, five different people have served as DOC commissioner and seven have served since the Nunez class action lawsuit was first filed. None were able to reverse the “deeply entrenched culture of dysfunction that has persisted across decades and many administrations,” the Legal Aid Society claimed.

In November, when Swain found the city in contempt of 18 provisions of the consent judgment, the judge said she agreed.

“The glacial pace of reform can be explained by an unfortunate cycle demonstrated by DOC leadership, which has changed materially a number of times over the life of the court’s orders, wherein initiatives are created, changed in some material way or abandoned, and then restarted,” she said in her order.

As a result, Swain said she was “inclined to impose a receivership.”

What might a receivership look like?

Putting a jail into a federal receivership is not unheard of, but it’s certainly rare.

A receivership is perhaps the most drastic order a judge can make, save for ordering an institution’s closure. It’s often seen as a last ditch effort to put a stop to harm caused by a government against those in its care.

Judges have ordered state and federal jails into receiverships about a dozen times in the country’s history, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Alabama’s entire prison system was taken over by a receiver in the 1970s and the medical operations of Washington, D.C.’s jails were handed over to a receiver in the 1990s. While the receiver’s powers in both cases varied, both Alabama’s prisons and D.C.’s jails saw improvements at the end of their respective receivers’ terms.

But receiverships are not permanent or perfect solutions – several decades after Alabama’s receiver completed their work, the U.S. Justice Department sued the state for unconstitutional treatment of men in its prison system.

What a receiver could look like in New York City – should Swain order one – is still very much up in the air.

For the past several months, the city has been meeting with the Legal Aid Society, the monitoring team and prosecutors with the Justice Department to negotiate the structure of a receivership.

The starting point for those conversations likely was based on the Legal Aid Society’s description of a receiver, which it detailed in its initial contempt filing.

Broadly speaking, a Rikers receiver would be charged with the “responsibility and authority to take all necessary steps to promptly achieve substantial compliance” with the consent judgment, the public defense firm said.

“The receiver shall provide leadership and executive management with the goal of developing and implementing a sustainable system that protects the constitutional rights of incarcerated people,” the filing read.

Under the Legal Aid Society’s proposed structure, the powers of a receiver would be vast.

Generally, they would have the “power to control, oversee, supervise, and direct all administrative, personnel, financial, accounting, contracting, legal, and other operational functions of DOC to the extent necessary to fulfill the mandate.” In many ways, they would supplant the commissioner, who would have their powers suspended and be required to work closely with the receiver.

A receiver would have the ability to enact new policies, hire and fire all staff and contractors, negotiate new contracts with labor unions and have unfettered access to all DOC records, facilities and incarcerated people.

Should the Legal Aid Society’s structure be enacted by Swain, the receiver would serve until the judge believes the city is in substantial compliance with the consent judgment. Given the knottiness of the crises that have plagued Rikers for decades, that could potentially mean the receiver would need years or decades to complete the job.

Norman Siegel, a lauded civil rights attorney who has publicly shared his interest in the receivership job, said that while he certainly believes tackling Rikers’ myriad issues would be a challenge, it would be possible.

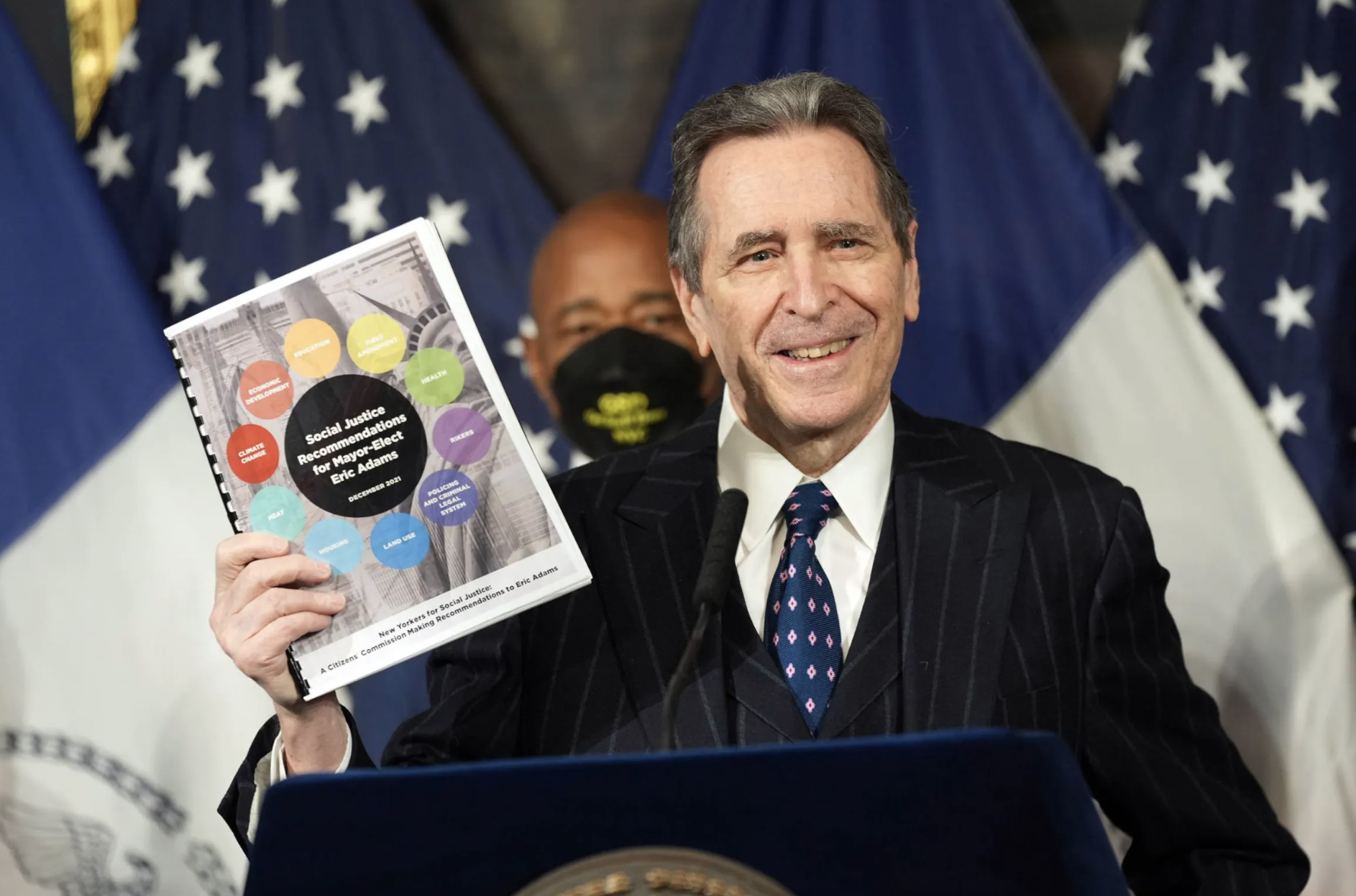

Civil rights attorney Norman Siegel, who is interested in becoming Rikers’ receiver, should federal Judge Laura Swain order one. File photo by Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office

While Siegel told the Eagle that he had ideas about how to lower the use of force rates in the jails, make conditions safer for younger detainees and hold alleged abusive staff accountable, he said that ultimately, the only way to “ameliorate” violence on Rikers is to generate real buy-in from everyone involved.

Siegel said the receiver should set up an office on the island and be available to detainees, officers, staff, the monitor and others 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Everyone involved has to know the receiver is “serious about it and persistent in trying to find out what’s the truth,” he said.

“I think it's contagious,” Siegel said. “Once they start to see that people are serious about this, the best in people comes up.”

But others aren’t so convinced.

Darren Mack, the co-director of the criminal justice advocacy group Freedom Agenda, said he believes Rikers Island is beyond repair. The only thing left to do, he said, is shut it down for good, as the city is currently mandated to do by 2027.

“I think there could be some potentially helpful impacts of a receivership,” Mack said. “But Rikers is like rabies – once you get it, it’s done.”

“Anybody that goes there, works there, is detained there – they don't come out the same,” he added. “There's no solution except for closing Rikers Island.”

However, it’s unclear how a receiver may impact the city’s plan to close Rikers Island.

Under Mayor Eric Adams, the city has fallen extremely behind schedule on the plan, missing several key benchmarks and pushing the completion date of the four borough-based jails set to replace Rikers well past the jail’s closure deadline.

The Legal Aid Society made no mention of the closure plan in its contempt motion or in its outline for receivership. Though the monitor has mentioned the plan in some of his reports, the court has yet to contend with how the two massive measures may play out simultaneously.

Adams, who has slowly worked his way up to full opposition of Rikers’ closure over the years, has turned to Swain in the past to circumvent city laws regarding criminal justice reforms related to Rikers. Earlier this year, he asked Swain to weigh in on a City Council law banning solitary confinement in the city’s jails. The mayor, who cited the Nunez case in an executive order suspending the law, claimed that putting the ban in place would violate numerous aspects of the consent judgment.

The law remains suspended and the monitor, who has been studying the law since the start of 2024, is expected to issue a report on his findings by the end of January.

The city, the Legal Aid Society, federal prosecutors and the monitor are set to appear before Swain on Jan. 24 to discuss what powers and responsibilities a potential receiver may have.

It’s unclear whether or not Swain will issue her ruling on the Legal Aid Society’s request to implement a receiver then, but if she does it will likely be months or more before a receiver is installed and asked to fix the violent mess on Rikers that so many have attempted – and failed – to fix before.