What’s Louis Molina’s job? City Hall won’t say

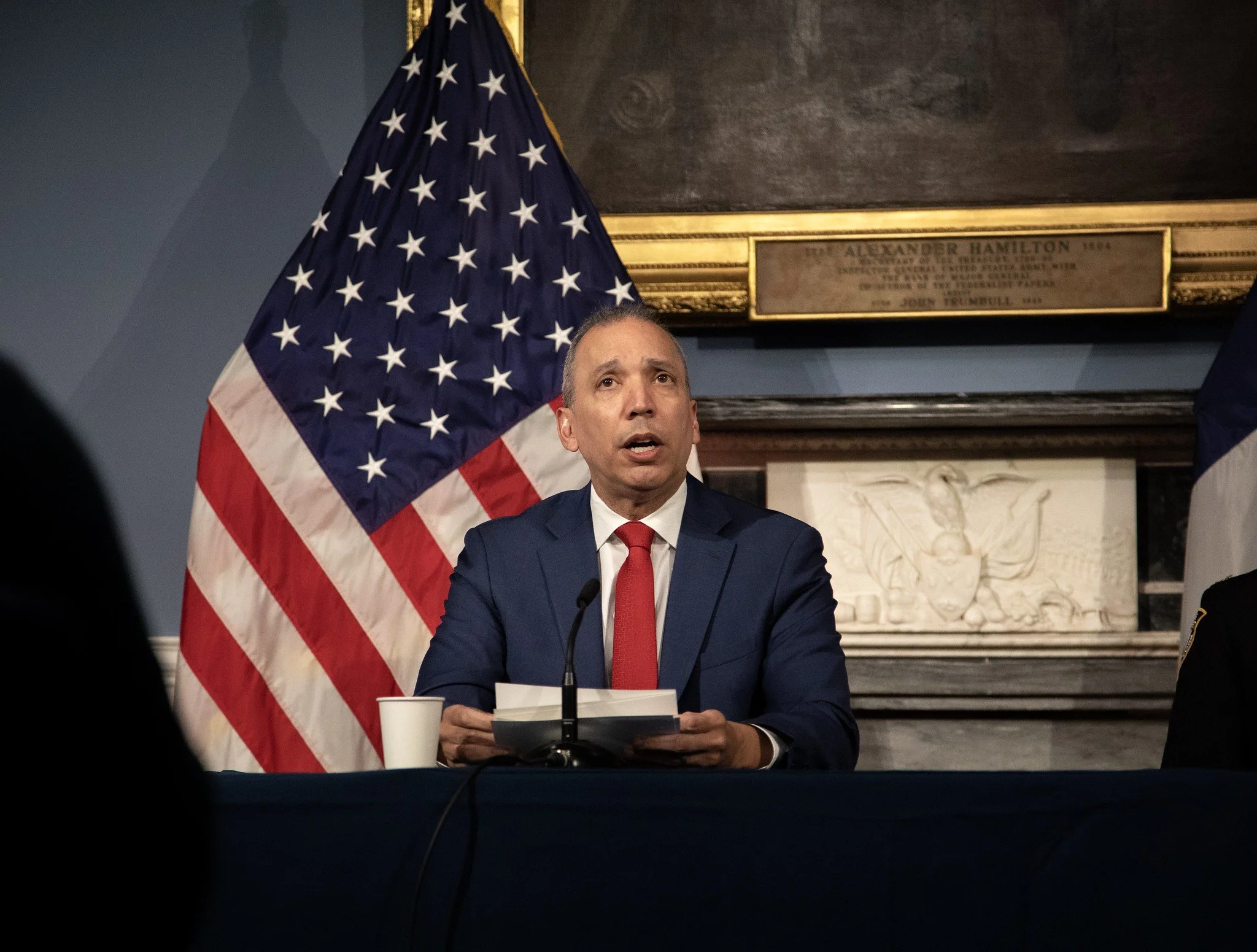

/Louis Molina made one of his first public appearances as assistant deputy mayor for public safety on Dec. 22 at a press briefing alongside members of the NYPD. What exactly his new role entails is unclear. Photo by Violet Mendelsund/Mayoral Photography Office

By Jacob Kaye

For just shy of two years, Louis Molina ran the city’s Department of Correction.

As the troubled agency’s commissioner, Molina was in charge of leading the DOC’s dwindling ranks of correctional officers, managing its growing population of detained New Yorkers and running its jails on Rikers Island, where over two dozen people died in the past two years.

Despite bringing the city closer than it’s ever been to having its jail complex stripped away from it and handed to a court-appointed authority, Molina was promoted to a new position in City Hall by Mayor Eric Adams late last year.

Now, what exactly it is that his job entails isn’t so clear.

City Hall has yet to publicly define Molina’s new role as assistant deputy mayor for public safety, a position the mayor’s office says falls directly under the management of Deputy Mayor for Public Safety Phil Banks. Though there are deputy mayors and assistant deputy commissioners, Molina appears to be the first-ever assistant deputy mayor.

Molina’s public profile since transitioning to the new gig – a transition that was delayed without explanation by around a month – has been minimal, with Molina only appearing at a handful of events and missing from others one might expect him to attend.

His position does not appear on the most recent mayor’s office organizational chart issued at some point in December – Molina’s move to assistant deputy mayor was made official on Dec. 8.

Numerous spokespeople for the mayor’s office have repeatedly ignored questions from the Eagle regarding Molina’s duties in his new job, including which city agencies fall under his purview or how much control or influence he has over the Department of Correction, which is now run by Commissioner Lynelle Maginley-Liddie.

The answers to those questions could have major implications on the future of the DOC and Rikers Island, which city law currently mandates be closed by August 2027.

Under Molina’s leadership, the department’s relationships with oversight authorities, including the Board of Correction and the City Council, as well as with the federal monitor charged with tracking conditions at Rikers Island on behalf of a federal judge weighing whether or not to strip control over the jail complex away from the city, have largely deteriorated.

During the two years Molina was responsible for the city’s jail complex, nearly all efforts to close its doors came to a halt. The lack of movement on the plan to close Rikers ultimately forced the City Council in October to reappoint the commission that crafted the original plan and ask them to create an updated one given “the context of the changed realities of a post-COVID New York City and the law mandating closure by 2027.”

Molina’s management of the DOC also angered criminal justice advocates, who now fear that his approach to public safety, one that they disapprove of, will be implemented not just within the DOC, but in every other public safety agency in the city.

“I think it's fair to say that since Molina was commissioner, he worked hard to stifle transparency at DOC and hide the abuses as well,” said Darren Mack, the co-director of Freedom Agenda. “There’s a great concern about how he would apply that approach to other law enforcement agencies in the role of assistant deputy mayor for public safety.”

What is Molina in charge of?

The power Molina has over the DOC or any other city agencies as assistant deputy mayor is unclear.

According to a press release from the mayor’s office announcing Molina’s appointment to the new position, the former commissioner works directly under Banks, who has the DOC, Department of Probation, Fire Department, the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, the Office of Municipal Services Assessment and New York City Emergency Management in his portfolio as deputy mayor.

But Molina’s influence over the city’s public safety efforts could extend well beyond Banks’ agencies.

The only description of Molina’s new job included in the release was a single sentence that read: “As assistant deputy mayor, Molina will be tasked with coordinating with all city agencies on public safety matters to ensure they align with Mayor Adams’ vision to keep every New Yorker safe.”

Whatever work Molina has been doing in the month since he was officially appointed appears to mostly be behind the scenes.

One of his only public appearances came on Dec. 22 – the Friday just before the Christmas holiday – when he led the administration’s semi-regular public safety briefing. Molina essentially served as the briefing’s host, touting the NYPD’s work monitoring protests, explaining their efforts to police quality-of-life issues and exploring some of the technology being utilized by the NYPD, including drones. Multiple reporters were denied the opportunity to ask Molina questions during the briefing by a mayoral spokesperson who claimed that neither the assistant deputy mayor nor the three officials with the NYPD sharing the dais with him would answer “off-topic” questions.

Then-Department of Correction Commission Louis Molina tours Rikers Island alongside Mayor Eric Adams, who recently promoted Molina to serve as the first-ever assistant deputy mayor for public safety. File photo by Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

Molina has also been absent from several other public safety-related events hosted by the mayor’s office in recent weeks.

He was not at the mayor and NYPD’s annual briefing ahead of the city’s New Year’s Eve celebration in Times Square, nor was he at a public safety announcement concerning the city’s new approach to enforcing laws in the city’s nightlife establishments.

Molina was also missing from the well-attended announcement of the appointment of Maginley-Liddie, who was named DOC commissioner on Dec. 8. Also missing from the announcement was Banks, who is widely rumored to be considering stepping down from his post within the administration.

Though Banks has aggressively denied that he’s on his way out of the door, Molina appears to be first in line to assume the deputy mayor position if it’s vacated.

Hank Sheinkopf, a political strategist, said that it’s a possibility that Molina’s promotion to assistant deputy mayor may be in service of a further promotion down the line.

“It would not be surprising for Molina to have more authority over a criminal justice system that’s in desperate need of repair,” he said.

‘A slap in the face’

Molina’s potential further elevation in the mayor’s administration would likely anger advocates, who were already vexed by Molina’s promotion to assistant deputy mayor.

“The mayor's decision to promote Molina was a slap in the face to the grieving families of the 28 people who lost their lives [in DOC custody] under this administration and to all those people who have been harmed and suffered during his tenure,” Mack said.

During Molina’s first year in office, 19 people in DOC custody died, marking a 10-year high. The following year, nine people died.

From the month he took office until the month he left, Rikers’ average daily population rose by nearly 1,000. Use of force incidents spiked during his first year before beginning to lessen – despite the decrease, use of force indents were far more common in 2023 than they were in the years before the pandemic. Fights between detainees and stabbings and slashings also occurred far more frequently under Molina than they did pre-pandemic. Under Molina’s leadership, the number of detainees not taken to medical appointments also rose, prompting legal action.

The City Council, several judges, the Board of Correction and others that oversee the DOC frequently disapproved of Molina’s running of the jails.

Throughout much of Molina’s tenure as DOC head, Steve J. Martin, the federal monitor appointed by federal Judge Laura Swain to track conditions in the jail as part of the ongoing civil rights lawsuit known as Nunez v. the City of New York, said that detainees and staff alike were at “grave risk of harm on a daily basis.”

In an October report issued nearly two years into Molina’s time as commissioner, Martin said that “the jails remain dangerous and unsafe, characterized by a pervasive, imminent risk of harm to both people in custody and staff,” a description of Rikers the monitor evoked on several occasions.

Beyond Martin’s criticism of Molina’s management of the city’s jails, the monitor also took issue with the former commissioner’s commitment to implementing reforms ordered by the court.

In a handful of reports filed in federal court in 2023, Martin described several incidents in which Molina allegedly attempted to interfere with Martin and his team’s work on Rikers.

In May, the monitor said that Molina and other top officials at DOC failed to properly report five serious incidents, two of which were fatal.

“One concerning trend has emerged where the department is no longer operating in a transparent manner,” Martin said in the report, adding that at times, he felt the department had been operating in an “obstructive manner.”

Not long after the report was issued, Swain, who had resisted calls for receivership proceedings the year prior, told the Legal Aid Society that they could begin the early stages of calling for Rikers to be taken from the city and handed over to a court-appointed authority.

“My confidence in the commitment of the city leadership to be all in on recognizing the need in working with the monitoring structure that the court has imposed in good faith and candor has been shaken by the incidents of the past few weeks,” Swain said at the time.

Then, in November, Martin said that the monitoring team had learned through an anonymous source that DOC leadership had quietly opened up a restrictive housing unit for detainees accused of committing arson. The monitor alleged that because the DOC hadn’t consulted the monitoring team about the opening of the housing unit – which was shut down almost immediately after Martin had learned about it – they should be found in contempt of court.

Swain agreed, calling the DOC’s opening of the unit “unacceptable and, in a word, contemptuous.”

During the hearing, Swain gave Molina, who appeared virtually and was only days removed from transitioning to assistant deputy mayor, an opportunity to speak. Though he said he hadn’t planned on giving any remarks, he defended his tenure as commissioner and claimed that he was “very, very transparent on a whole host of issues.”

After finding the DOC in contempt, Swain said that one of her only reasons for having faith that conditions might improve in the notorious jail complex was that a new commissioner had been appointed.

Whatever authority Molina has retained over the DOC in his new position was not discussed at the hearing.

Some members of the city’s Board of Correction, the DOC’s civilian oversight body, would also likely be displeased if Molina’s control over the agency continued to grow.

Molina largely bucked the board’s authority during his two years in office, attending only 10 of the 16 public hearings the board held during his tenure.

On some occasions, Molina would miss meetings without a detailed or preemptive explanation. At the meetings he did attend, he often clashed with at least several members of the board.

Similar clashes occurred in the City Council during oversight hearings led by Criminal Justice Committee Chair Carlina Rivera, who declined to speak with the Eagle for this story.

Speaking with the Eagle in July, Rivera criticized Molina and the mayor for their efforts to make the agency less transparent. Largely, she appeared disappointed in the then-commissioner’s reign leading the DOC.

“We want nothing more than the Department of Correction to be able to manage the jail system in a compassionate and competent way, but it hasn't happened for a long time,” Rivera told the Eagle. “The fact that we are getting to this point where the commissioner who was once praised is now seen as really kind of letting things get out of control, I mean, that's really serious.”

Not all who worked with Molina were opposed to his promotion. Benny Boscio, the president of the Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association, mostly got along with Molina during his tenure as commissioner and said in a statement that he supports Molina’s elevation to City Hall.

“Former Commissioner Molina entered our agency during one of the worse crises in the history of the department, facing many challenges,” Boscio said. “We didn’t always agree on everything but appreciated his willingness to listen to our perspective from the boots on the ground and always had an open door policy. We look fowrwad to working with him in his new capacity as assistant deputy mayor for public safety.”

This story was updated at 6:21 p.m. on Thursday, Jan. 4 with a statement from COBA President Benny Boscio.