A century of violence, chaos and death: Inside the troubled history of Rikers Island

/For nearly 100 years, violence, chaos and death have defined the jails on Rikers Island. Some say that could change with the appointment of a federal receiver. But anyone running the jail complex will have a lot of history to contend with. Eagle file photo by Jacob Kaye

As a federal judge considers taking Rikers Island out of the city’s control and handing it to a court-appointed receiver, the Eagle is looking back at the history of the city’s troubled jail complex – which we have covered extensively since our founding in 2018 – in an effort to understand how the city arrived at this critical moment. While this story mostly covers the lead up to the call for receivership, part two of the story mostly turns ahead to what the future of the jails on Rikers may look like.

By Jacob Kaye

For nearly 100 years, New York City has been housing its detainees in jail cells on Rikers Island. And for all of that time, the jail complex has been known almost exclusively as a place of violence, chaos and death.

That has certainly been the case for the past decade, when conditions in the jails have been under the watch of a judge who will soon decide if the city should be allowed to remain in control of Rikers, or if the federal government should take it over.

Dating back to 2014, over 100 people have died on the island while in the city’s custody. Over that same period, Rikers Island has seen tens of thousands of assaults, fights and beatings by officers.

The jail facilities on Rikers, many of which are infested with bugs and vermin, have long deteriorated to the point where their crumbling parts are used as weapons. Morale among officers has fallen precipitously in the past decade, as well – in 2021, officers effectively were in open revolt of the agency that employed them, going AWOL in large numbers for the better part of a year.

Rikers has also been a constant source of litigation and costly taxpayer-funded settlements. The Depatment of Correction has been sued for failing to provide medical care to detainees, for allowing brutal fights to unfold with guards’ permission, for dozens of wrongful deaths and for their failure to prevent over 700 instances of sexual abuse over the past several decades. In 2022 alone, the city paid out $37 million in cases brought by detainees alleging abuse by guards.

But perhaps no lawsuit stands to have more of an impact on Rikers than a civil rights case known as Nunez v. the City of New York.

The original lawsuit, which was filed in 2011, began with a single claim by then-detainee Mark Nunez, who said that a group of correctional officers unjustly beat him and his fellow detainees in March 2010. A year later, the case grew to a class action lawsuit that aimed to “end the pattern and practice of unnecessary and excessive force inflicted upon inmates of New York City jails by Department of Correction uniformed staff.”

The scope of the case grew even larger when, in 2015, the city entered into a consent judgment ordering them to protect the constitutional rights of their detainees. The consent judgment would further expand over the years as crises after crises cropped up in the jails.

While some years proved safer than others on Rikers Island, violence continued relatively unabated over the next decade.

In 2023, the Legal Aid Society, which represents the class of detainees in the case, officially asked federal Judge Laura Swain to hold the city in contempt for failing to meet the requirements of the judgment. The levels of violence, disorder and, crucially, use of force incidents were higher in recent years than they were the year the judgment was entered, the Legal Aid Society claimed.

In 2024, Swain agreed, ruling the day before Thanksgiving that “the current rates of use of force, stabbings and slashings, fights, assaults on staff, and in-custody deaths remain extraordinarily high, and there has been no substantial reduction in the risk of harm currently facing those who live and work in the Rikers Island jails.”

As a result, the judge said that she was “inclined” to take control of the jail complex away from the city and hand it over to a court-appointed third party, known as a federal receiver.

The dramatic measure could be the only way to finally turn the tide on the 100-year history of violence in the city’s jails, supporters of receivership say. A receiver would likely be granted the power to cut through the city’s red tape and make major changes to the management of the jails currently unavailable to the Department of Correction’s commissioner. A receiver also would answer directly to a judge, unlike the DOC, which currently answers to a mayor who has, year after year, fought against attempts to reform the jails.

But even if a receiver represents a unique opportunity to fix Rikers, they will still have the heavy weight of the jail’s history to contend with.

Nearly all of the troubles seen on Rikers in recent years are not new. Reflections of those crises have already played out at some point in the city’s not-so-distant past – and few were permanently rectified.

Beyond the fights, suicides, gang violence, drugs and aggression from officers, the city has previously attempted – and failed – to shutter Rikers in favor of smaller, borough-based jails, just as they have been attempting – and failing – to do over the past decade. And that previous closure attempt also happened to coincide with a major ruling from a judge, who ordered the city to clean up conditions in the jails, just as a different judge has been doing for the past decade.

Should the extraordinary measure of stripping the city of its ownership of Rikers Island be taken in the coming months, a receiver would not only be tasked with managing the specific crises that have vexed the DOC in recent years, but also with meaningfully addressing the cruelty that has defined Rikers for nearly a century.

A repeating, violent history

New York City purchased Rikers Island in the 1880s from the descendants of Abraham Rycken, a Dutch settler who took possession of the island in 1664 and for whom the island is now named.

But before the city decided to build jails on Rikers, it turned the island into a dumping ground.

Trash, ash and manure were piled high on Rikers Island for decades, expanding the footprint of the island from 100 acres to over 400 acres. The landfill attracted rats, which flourished on the island until the city attempted to kill them with poison gas.

The heaps of landfill eventually grew so tall that Rikers, which, in some places, floats only 300 feet from Queens’ shoreline, became an embarrassment for some city leaders, including Robert Moses, who feared the garbage-filled island would alarm tourists coming to Queens for the 1939 World’s Fair.

While deciding to send the trash to Staten Island, the city chose to replace the refuse on Rikers with jails.

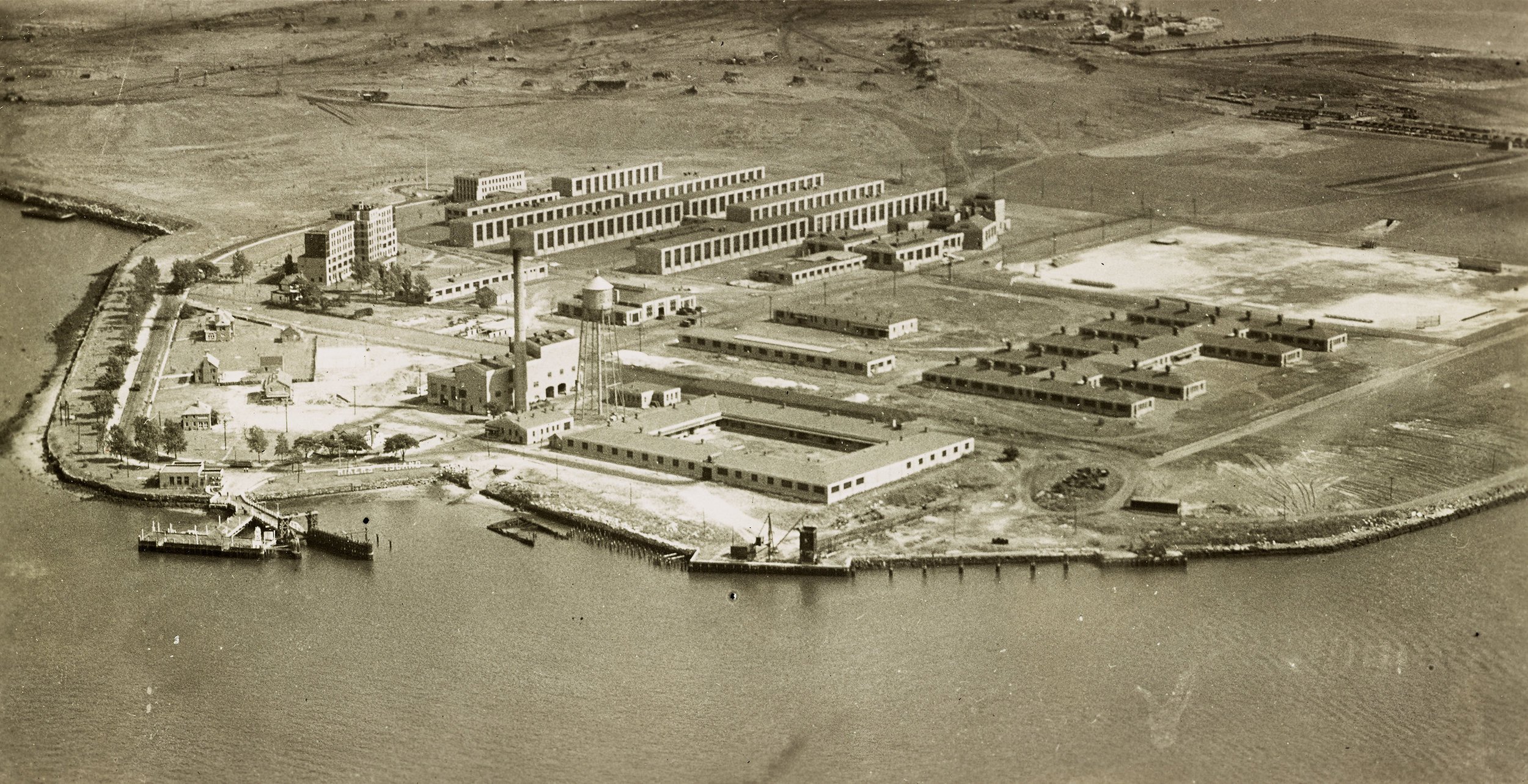

An aerial view of unfinished Rikers Island penitentiary buildings in 1936. Photo via Department of Corrections/NYC Municipal Archives Collection

The first jail on Rikers opened in 1935. The new facility was designed to replace the city’s main jail complex on Blackwell Island, which is now known as Roosevelt Island.

Much like Rikers today, New York City’s first jails on Blackwell Island were notorious for their horrifying conditions. The city not only housed its detainees there, but also those with intellectual disabilities and mental health issues. The scandalous treatment of the island’s inhabitants were exposed in the late 1800s by then-budding investigative reporter Nellie Bly, who went undercover by getting admitted to the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell Island. Bly, who is now regarded as a pioneer of investigative journalism, went on to publish a number of stories about the poor treatment of patients on the island. The exposés sparked a number of reforms and generally contributed to a changing attitude about the conditions on the island. Soon after, the city would begin to move toward shutting the island down entirely.

But the city’s new jails on Rikers Island would not end up being much of an improvement.

During the island’s construction in 1932, a steamboat taking workers to and from Rikers exploded in the East River, killing 72 people. The accident was a sign of troubling times to come.

When the new facilities were eventually completed several years later, they were found to have been shoddily built. A report by the city’s Commission on Accounts found that some of the buildings had cracks, according to the city’s Department of Records and Information Services. The poor construction was likely a result of corruption – Rikers’ architects had been awarded a no-bid contract and dolled out construction rights in a way that violated the city’s contracting process.

Over the next several decades, the population on Rikers grew and so too did the need for new jail facilities. While riots, fights, deaths and scandal became regular occurrences on the island through the years, they appeared to reach a peak as the 1970s began. At the start of the decade, the population on Rikers was nearly double what the island was designed to hold.

The overcrowding led to a detainee riot and a work stoppage by correctional officers, according to the Department of Records and Information Services.

Also around that time, a federal judge found conditions at Rikers to be unconstitutional and ordered the DOC to reduce the jail’s population and make Rikers’ facilities more habitable for those locked up there.

That’s when the city first decided it may be time to scrap the jail project on Rikers altogether.

During Mayor Ed Koch’s first years in office, the city issued a report detailing the “decrepit condition [on Rikers] which creates a potentially dangerous environment for both staff and inmates,” according to the Department of Records and Information Services. Noting how costly it would be to fix the existing buildings on Rikers, city officials instead proposed selling the land to the state and building eight small jails in Queens, Brooklyn, the Bronx and Manhattan.

The plan was controversial and eventually fell apart by the early 1980s, when the Office of Budget Review issued a report claiming that building the new jails would be significantly more expensive than originally proposed. As he ran for his second mayoral term, Koch dropped the idea altogether and not only allowed Rikers to stay open, but facilitated its growth.

The crisis on Rikers Island reached one of its many peaks during the early years of Ed Koch’s first term. Photo via Mayor Koch Collection/NYC Municipal Archives

Thousands of beds were added to the jail complex over the next several decades as the crack epidemic and the War on Drugs fueled high rates of incarceration. Several multi-day riots broke out during the 1980s as beatings by officers, gang fights and a lack of order and discipline among staff came to rule the island.

By 1990, around 20,000 New Yorkers were being held on Rikers.

That’s around the time that Darren Mack, who now serves as the co-director of the criminal justice advocacy group Freedom Agenda, was arrested and sent to the jail as a teenager.

“There was always a constant threat of being harmed by people who were detained or by staff,” Mack told the Eagle. “Staff, particularly, because they kind of control Rikers Island through the constant threat of violence.”

At one point during his time on Rikers, Mack said he was being held in solitary confinement when a detainee in the cell next to his attempted to hang himself. Guards flooded the detainee’s cell, cut him down and began to beat him, Mack said.

“Something was happening every day,” he said.

Violence on Rikers continued through the aughts, when at least 260 people died while being held in the jails.

The deaths continued as the city entered the 2010s. At least a dozen people died each year on Rikers during the first four years of the decade.

But as the decade developed, so too did two events that each would hold the potential to change Rikers forever.

In 2014, New Yorkers elected Bill de Blasio to serve as their next mayor. Under de Blasio, the city would pass a law ordering the closure of Rikers by 2027. While the city is currently wildly off track to close the jail complex by its deadline, it also has never been closer to seeing the island’s use as a penal colony come to an end.

But before the closure plan came the Nunez lawsuit and the consent judgment borne from it, which now threatens to, at least temporarily, end the city’s control over Rikers.

‘A glacial pace’

Mark Nunez was a teenager when, in 2011, he sued the DOC, claiming that a captain had brutally beaten him for no reason the day before he was sent off to serve his sentence in a state prison.

In the complaint, Nunez described an isolated incident. It began when an officer noticed that food from the night before had been left out in a pantry. The officer, upset by the mess, ordered the detainees in the area, including Nunez, back into their cells. Nunez told the officer he thought it was unfair that he and his fellow detainees should be locked in their cells because of a mess left behind by someone else. That’s when the officer called in other officers, who soon showed up in riot gear, according to the filing.

Nunez said he was maced, punched and beaten with a radio by one of the officers because of his soft refusal to go back into his cell.

In all, the filing was no more than a couple hundred words long. But the teenager’s account rang true for thousands of others who spent time incarcerated on Rikers and soon was brought as a class action lawsuit. At the time, it was the fifth class action suit alleging a “pattern of brutality in New York City’s jails” dating back to 1990.

After dozens of hearings in the case, the city reached a deal with the Legal Aid Society, federal prosecutors and attorneys at Emery Celli Brinckerhoff & Abady, LLP to enter into a consent judgment touching on a range of issues within the jails.

Though the 76-page order, which included over 300 provisions, centered around use of force incidents, it also required the DOC to address staff discipline, training, video surveillance, officer recruitment, the safety of teenage detainees, detainee discipline and more.

The agreement also resulted in the appointment of longtime corrections administrator Steve J. Martin to serve as the court’s monitor tasked with tracking the city’s compliance with the judgment.

In his first-ever report, Martin noted that “[h]istory has proven that the road to sustainable reform is seldom swift or painless; it must be traversed in an incremental, wellreasoned, and methodical manner.” He seemed mostly hopeful that improved conditions on Rikers were possible, telling the judge “the department has committed to meet the challenges necessary to reform the overall management of the New York City jails.”

That optimism would not last.

Around eight years after his first report, Martin’s 18th and most recent report carried more of a frustrated tone about the speed at which reform on Rikers had been pursued.

“The department remains mired in dysfunction as it attempts to address a variety of polycentric problems where each element is intertwined with others,” Martin wrote in November 2024. “Without both commitment and competence among all members of the department’s staff, the reform effort will continue to advance at a glacial pace.”

Though there were several years where Martin appeared encouraged by the city’s efforts to implement changes on Rikers, there were few times over the years where Martin found the city even remotely close to being in compliance with the consent judgment.

“The department continues to struggle with many of the problematic, excessive, and unnecessary uses of force that gave rise to the consent judgment,” he said after the first year of monitoring.

“Despite the department’s efforts this monitoring period to achieve compliance, the department has not yet made significant progress toward the primary goal of reducing the use of unnecessary and excessive force,” Martin said after the second year.

By 2019, the use of force rates had grown higher than they were the year the consent judgment went into effect. That same year, a trans woman named Layleen Polanco died while in solitary confinement on Rikers, sparking not only a new push to ban the practice classified as torture by the U.N. but also a push to close Rikers down and replace it with more “humane” jails.

Nonetheless, the city’s criminal justice system appeared to be heading in a direction toward reform. Statewide, new bail and discovery reform laws were soon to go into effect with the hope that fewer people would be sent to jail pre-trial and that those who do would see their cases resolved sooner. Crime also fell to a historic low in 2019. As did the population on Rikers Island, which hit 5,400 detainees in February 2020, which, at the time, was the smallest population on Rikers in decades.

Then, the pandemic struck.

Surrounded by corrections officers, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio holds a news conference on Rikers Island in New York, Thursday, March 12, 2015. AP file photo by Seth Wenig

Like everywhere else in New York City, life on Rikers came to a halt during the earliest months of the pandemic. Programming designed to keep detainees engaged and out of trouble was put on hiatus, as was the jail’s laundry service, barber shop and law library. Detainees on Rikers, a vast majority of whom are being held pre-trial, saw their cases come to a standstill as courts throughout the city slowed their operations down significantly.

Officers also quickly became ill and began to miss work in large numbers. With tensions growing on Rikers, some officers began to skip out on their jobs, not even bothering to tell their supervisors they wouldn’t be making it in for a shift. With fewer officers around to escort detainees from one place to another on Rikers, those incarcerated there became even more stagnant. At one point during the pandemic a group of detainees went on a multi-day hunger strike in protest of the worsening conditions.

Deaths on Rikers also again began to rise.

In August 2021, then-DOC Commissioner Vincent Schiraldi called reporters to his office on Rikers in an effort to beg officers to return to their posts. That month, nearly 100 officers per day had been going AWOL.

But before he could make his plea, he had to first make an announcement – a man had died on Rikers that morning, bringing the DOC’s deaths in custody that year to nine. Seven others would die before the end of year and 19 more would die in 2023, marking a 10-year high.

While Martin acknowledged toward the end of 2020 that the DOC had “established a record of non-compliance in the most fundamental goals of the consent judgment,” his true admonishment of the city wouldn’t come until the election of Mayor Eric Adams and the installation of his first DOC commissioner, Louis Molina.

Though Martin initially expressed optimism about Molina’s willingness to work with the monitor and his team, their relationship quickly soured as conditions on Rikers continued to deteriorate.

But still, after Molina’s first year at the helm, Martin blamed Rikers’ dark history more than he did Molina for the jail’s troubles.

“The perfect storm presented by the COVID pandemic, the ensuing staffing crisis, and a revolving door of leadership – three different commissioners in nine months, May 2021 to January 2022 – threatened to collapse a system that was already reeling from a poor foundation weakened by decades of neglect and both internal and external mismanagement,” Martin said in April 2023. “Thus, the department has been trapped in a state of persistent dysfunction, where even the first step to improve practice has been undercut by the absence of elementary skills and basic correctional practices and systems.”

But as 2023 continued, Molina, who had worked with the monitor in 2016 as the DOC’s chief internal monitor, would begin to cut off communication with Martin, angering the monitor and Swain, who had already been asked the year before by the Legal Aid Society to order a receivership over Rikers.

In May 2023, the monitor said in a court filing that Molina and the DOC had failed to report five serious incidents, several of which resulted in the death of detainees. After the monitor learned of the incidents, Molina allegedly begged him not to tell the judge what had happened so as not to “fuel the flames of those who believe that we cannot govern ourselves.”

Swain went on to call Molina’s attempts to influence the monitor’s reporting “disturbing.”

“These actions are, simply put, unacceptable,” Swain said.

The incidents marked the beginning of the end of Molina’s time as commissioner. A month after the monitor’s report, Swain said she would allow the Legal Aid Society to again request the appointment of a receiver.

In November 2023, the public defense firm officially called on Swain to order a federal takeover of Rikers.

The Legal Aid Society’s argument for contempt and the appointment of a receiver was relatively simple.

Nearly a decade after the consent judgment first went into effect, the DOC had been unable – and, in some cases, unwilling – to make the jails safer. A number of metrics, including use of force incidents, had not just been stagnant over the years, but had worsened.

“The levels of violence and brutality in the city jails that exist today were unimaginable when the consent judgment was entered in 2015, and the city has demonstrated through eight years of recalcitrance and defiance of court orders that it cannot and will not reform its unconstitutional practices,” Mary Lynne Werlwas, the director of the Prisoners’ Rights Project at The Legal Aid Society, said after the public defense firm filed its contempt motion.

There was no monetary punishment or order from a judge that would get the city to finally turn around conditions on Rikers, the Legal Aid Society argued. The only thing left to do would be to forcibly take the jail complex away from the city, and bring someone new in to take it over.