DOC boss denies knowing about Rikers’ ‘worst-kept secret’

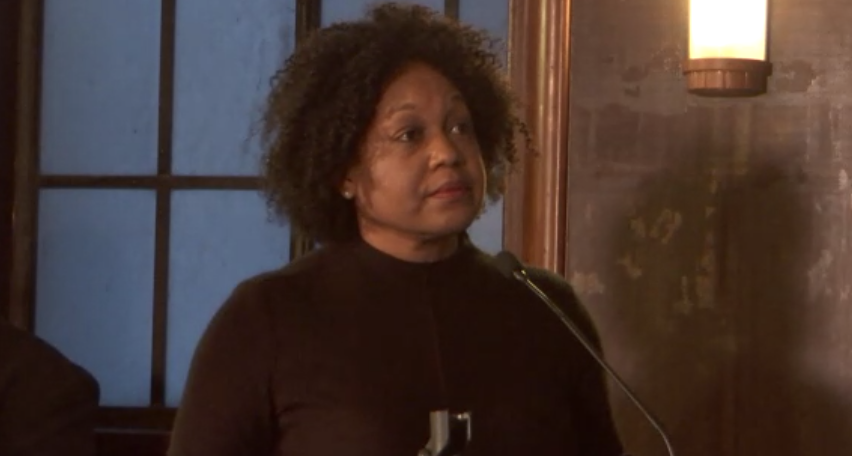

/Department of Correction Commissioner Lynelle Maginley-Liddie claimed on Tuesday that she had no knowledge of the practice of deadlocking, or holding mentally ill detainees in cells without access to medical care for days or weeks at a time. Screenshot via BOC

By Jacob Kaye

The head of the city’s Department of Correction had little to say Tuesday when asked about allegations that officers have been regularly locking up detainees with mental health issues for days or weeks at a time in solitary confinement, blocking their access to medication and attention from doctors.

Appearing before the Board of Correction on Tuesday during the citizen watchdog panel’s monthly meeting, Department of Correction Commissioner Lynelle Maginley-Liddie was relatively mum when questioned about “deadlocking” detaintees, which first came to light when a whistleblower detailed the concerning practice before the BOC last month.

Deadlocking, as described by former Rikers Island social worker Justyna Rzewinski during the BOC’s October meeting, is an allegedly well-established practice in the city’s jails where officers indiscriminately lock up mentally ill detainees, cutting them off from health care, services and other people in DOC custody. The practice appears to be in violation of the BOC’s rules that govern the rights of detainees on Rikers Island, a jail complex where half of the incarcerated population has been diagnosed with a mental illness.

Rzewinski, who worked for nine months as a social worker with Correctional Health Services in the troubled jails, said she left the job after nine months because of the “extremely traumatic” experience of witnessing the alleged practice. She had first joined CHS in December 2023, the same month Maginley-Liddie was appointed to lead the struggling agency.

While Maginley-Liddie didn’t outright deny the practice exists on Rikers Island on Tuesday, she claimed that she had no knowledge that deadlocking was being used by officers as a form of punishment against detainees already being held in mental health units.

“I was not aware of the practice happening,” Maginley-Liddie said. “If it does occur, it will be investigated and people will be held accountable for that.”

But according to the commissioner, the DOC is not conducting an investigation into the allegations, which prompted widespread condemnation from the BOC, criminal justice advocates and lawmakers.

Instead, Maginley-Liddie said she referred the allegations to the Department of Investigation, which sometimes takes years to issue its findings on any given investigation.

But several attorneys testifying on Tuesday told the BOC that the practice is still very much in use.

“This is an ongoing issue, it’s still happening and it’s extremely widespread,” said Dorothy Weldon, a special litigation attorney with the New York County Defender Services.

Weldon said that after the public defense firm learned about the practice last month, they began asking their incarcerated clients whether or not they had experienced being deadlocked.

“Every day we are learning something new and horrifying about this practice,” she said, calling deadlocking the “worst-kept secret on Rikers.”

“I’m flabbergasted that the commissioner could not be aware of these things going on,” Weldon added.

Michael Klinger, an attorney with Brooklyn Defender Services, said that his firm had also confirmed the indiscriminate use of deadlocking on Rikers.

Klinger alleged that entire housing units had been deadlocked at one time and that detainees had to yell out of windows to neighboring housing units in order to alert others that someone was in need of medical attention.

In another case, Klinger claimed that one of BDS’ clients was locked in a cell with no running water for a week. Without running water, the toilet would not flush. The feces in the room attracted insects, which soon swarmed the cell.

The account appeared to mirror an incident Rzewinski told the BOC last month.

“Many would smear feces all over themselves and their cells,” Rzewinski said. “They would sit in their cells almost catatonic, with flies and maggots and feces all over.”

“This is how these individuals woke up, went to sleep and ate the meals that were delivered to them through a slot three times a day,” she added.

Klinger said that while some correctional officers had told him that deadlocking was used by officers who had “gone rogue,” it also appeared to be used by officers throughout the jail complex.

Last month, Rzewinski told the BOC that there was no guidance for deadlocking, and that officers would sometimes lock up detainees for looking at them in a way they felt was inappropriate.

The former Rikers worker recounted one incident in which a detainee with serious mental health issues and a medical condition that required daily medication was deadlocked.

The detainee was initially brought to Rzewinski’s unit after being deadlocked in a different facility. The former social worker said that when he arrived, the detainee was “non-functioning,” and spent all day screaming, banging, smearing feces around the cell and tearing up his mattress.

Rzewinski said the detainee, while not deadlocked, showed some “odd behavior, like standing by my door and staring at me.” She said however that the behavior, which lasted throughout the week, did not make her fear for her safety because she “knew he was severely mentally ill and was extremely shell shocked.”

When she returned to Rikers on a Monday after not working over the weekend, she had learned that the detainee had been deadlocked after an officer said he “looked at her inappropriately and made her feel uncomfortable.”

“There were no allegations of touching or physical contact or threats,” Rzewinski said. “She just thought that he was weird and she wanted him to be locked in.”

Not long after, the detainee was eventually put back on medication and again became communicative, Rezewinski decided to resign.

“He blamed himself for being locked in… [but] I assured him that it wasn't his fault,” she said. “As I spoke to him, I kept thinking about what had been done to him, and how this healthy version of him was who he should have been all along. After ending the session, I went into my office and cried.”

“That was the moment that reaffirmed that leaving was the right decision for me,” she added.

On Tuesday, the BOC passed a resolution condemning the practice. The resolution also called on the DOC to regularly report “each instance of individualized involuntary lock-ins.”