‘Dysfunction remains the reality’: Legal Aid makes final arguments for federal takeover of Rikers

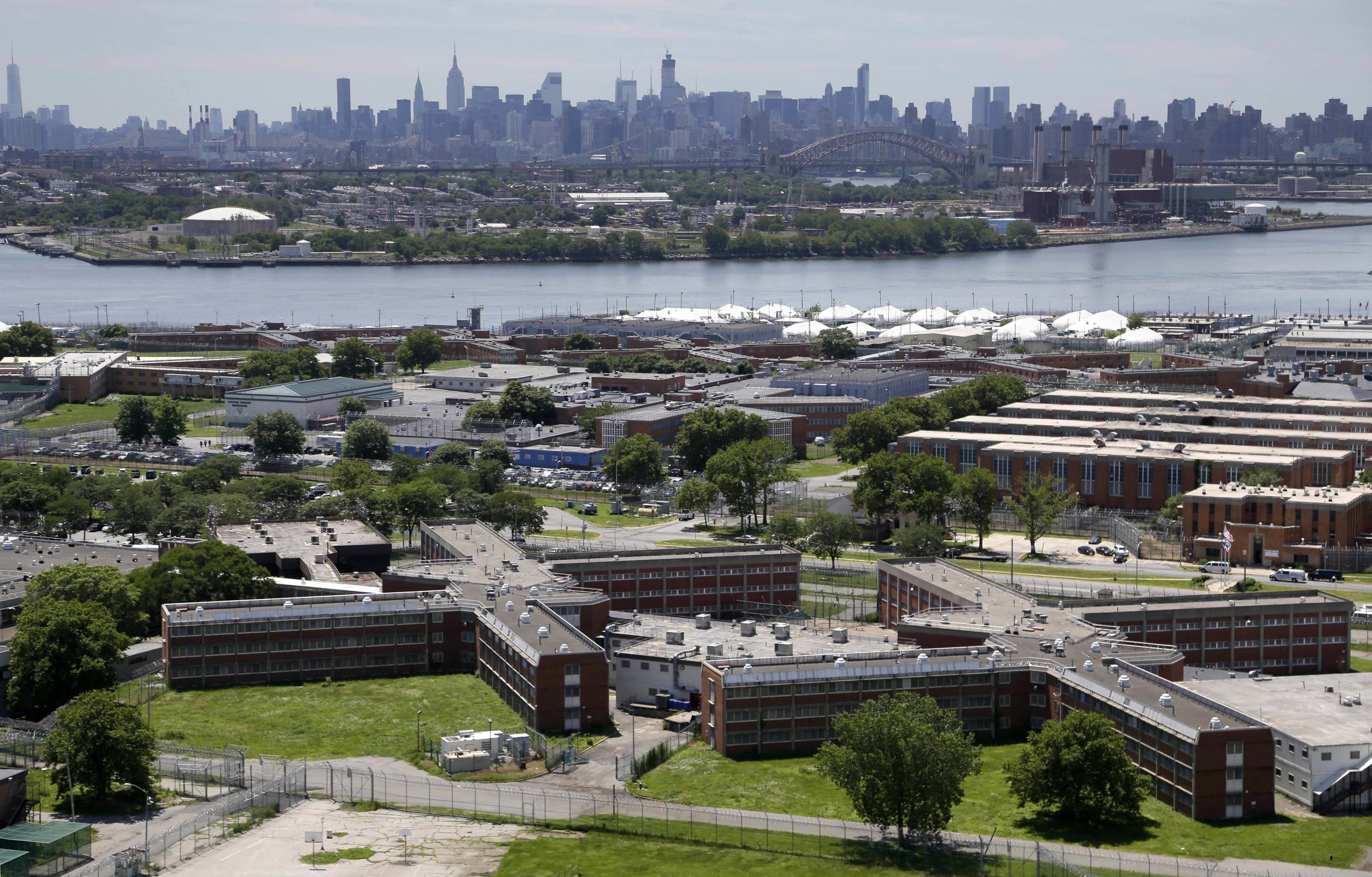

/The Legal Aid Society made its final arguments calling for a judge to install a federal receiver on Rikers Island, claiming the city has failed to correct violent conditions there in violation of a 2015 consent judgment. AP file photo by Seth Wenig

By Jacob Kaye

Despite the city’s instance that if given more time it can turn around its troubled jail complex on Rikers Island, the Legal Aid Society said in a Thursday court filing that enough was enough, and reiterated its call for a federal judge to strip control of the jail from the city and hand it over to a court-appointed authority.

In the latest filing in the ongoing civil rights case known as Nunez v. the City of New York, the Legal Aid Society said that little has changed in the half year since it first called on federal Judge Laura Swain to place Rikers into what is known as a federal recievership.

The Legal Aid Society said that the “devastating status quo,” which includes high rates of violence between officers and detainees, violence between incarcerated New Yorkers and dozens of deaths, has remained over the past eight years, despite countless promises to change made by the city’s Department of Correction – not to mention, a 2015 consent decree requiring the city correct dangerous conditions at its jails.

"[The city] ask this court to again trust their plans and promises instead of their actual track record,” the public defense firm said in their filing. “Promises abound. Dysfunction remains the reality."

Most damning, Legal Aid claimed, was that officers have continued to use violent and unnecessary force against detainees, the central issue to the original lawsuit and consent decree. In fact, the attorneys, who represent a class of incarcerated New Yorkers in the lawsuit, say the DOC’s use of force issues have only gotten worse at various points over the past near-decade.

“Eight years of federal court monitoring of a consent decree and seven remedial orders have not abated the violence and harm inflicted on people held in New York City jails, including routine blows to the head and beatings while in restraints,” the Legal Aid Society said in a statement in regard to their latest filing.

“The current commissioner agrees that the violence is ‘unacceptable,’ but the city has not demonstrated it has the will or capacity to change its course and implement the reforms needed to protect our clients’ safety and their constitutional rights,” they added. “Once again, the city asks that we ignore its disastrous record and rely on another set of promises that history tells us will overwhelmingly fall short.”

The Legal Aid Society’s recent filing will likely be the last in a series of filings made in the case before Swain is expected to make a decision on whether or not to install a receiver over the city’s jails.

Though the public defender organization first asked Swain to begin receivership proceedings in 2022, the federal judge ordered the DOC to instead craft an “action plan” alongside the federal monitoring team led by Steve J. Martin, who has been deputized to serve as the judge’s eyes and ears inside the jail complex for the past eight years.

However, after several allegations from Martin, the Legal Aid Society and federal prosecutors that the action plan was not being followed, Swain granted the public defenders’ request to formally call for receivership.

The public defender organization made its first official arguments for the extreme judicial action in November.

The over 100-page filing attempted to lay out the case for receivership, arguing that the DOC had “overwhelmingly” not complied with the heart of the 2015 consent judgment. Use of force incidents have continued, and the DOC hasn’t done much to hold staff accountable when they cross the line, the filing argued. The Legal Aid Society also argued that the DOC has generally failed to keep detainees safe on Rikers Island and that “the risk of severe harm in the jails is as imminent, if not more imminent, in the present moment as it was when the consent judgment was entered.”

The city’s attorneys responded in May, arguing a receiver wasn’t necessary to improve conditions on Rikers Island, where over two dozen detainees have died in the past two years.

Much of the city’s argument against federal receivership rested on the shoulders of Lynelle Maginley-Liddie, the commissioner of the Department of Correction appointed to the role by Mayor Eric Adams in mid-December. Maginley-Liddie replaced former DOC Commissioner Louis Molina, whose relationship with the monitor had grown so sour that Martin said he wasn’t sure if the jails could be made safer under Molina’s leadership. Swain had only allowed the Legal Aid Society to move forward with its receivership request after a series of incidents in which Martin alleged that Molina had bucked the monitor’s authority.

Maginley-Liddie’s appointment to the role was seen by many as an attempt to stave off receivership. At nearly each step in her career within the DOC, the licensed attorney had worked on ensuring the department was in compliance with the consent judgment. She also appeared to be more committed to reform than her predecessor, a cause for celebration among the monitoring team.

Though the city claims that the appointment of Lynelle Maginley-Liddie as Department of Correction commissioner in December is reason for them to remain in control of Rikers Island, the Legal Aid Society reiterated in a court filing on Thursday that they believe the violence in the jail is bigger than any one commissioner. File photo via NYC mayor’s office

“The monitor and the monitoring team have worked with Commissioner Maginley-Liddie for many years and have developed a good working relationship with her during this time,” the monitor said in a December report. “In her work at the department, the monitoring team has found the commissioner to be transparent and forthright.”

But in their filing on Thursday, the Legal Aid Society said that “the appointment of a new commissioner is neither sufficient to address the city’s systemic violations of this court’s orders, nor an adequate substitute for the appointment of an independent receiver.”

The praise showered on Maginley-Liddie following her appointment was not notable, the public defenders said.

“Indeed, every commissioner appointed during the life of the consent judgment was similarly lauded at the start of his or her term,” they said in the filing.

“The city offers no reason why the most recent commissioner’s experience with DOC or commitment to collaboration will succeed in bringing DOC into compliance where past commissioners with similar credentials have failed,” the Legal Aid Society added.

Federal prosecutors in U.S. Attorney Damian Williams’ office, who have joined the call for receivership, said in a separate filing on Thursday that they agree with the Legal Aid Society’s assessment of the new commissioner.

“To be clear, the government has no reason to doubt Commissioner Maginley-Liddie’s commitment to the reform effort and appreciates her recent efforts to consult and collaborate with the monitoring team,” prosecutors said. “Nor does the government question the soundness of some of the plans and initiatives announced under her leadership.”

“However, her appointment and these recent steps do not change the fact that the city and the Department have institutionally failed to exercise reasonable diligence to comply with the Nunez Orders for years,” they added. “The voluminous evidence before the court, including the Monitor’s most recent exhaustive report, support a finding of contempt.”

What comes next?

The Legal Aid Society, federal prosecutors, the federal monitor and the city are currently scheduled to submit a joint status report on the state of the jails on July 2.

The filing is scheduled to come a week before the next scheduled court appearance in the case, during which Swain could rule on whether or not a receiver should be appointed.

Should Swain order a federal takeover of the jail complex, it’s not likely the receiver would begin their work any time soon.

It would likely take anywhere from several months to a year to define the role of a receiver.

The scope of a receiver’s powers, should one be implemented, could be relatively vast.

A receiver would likely have the power to hire and fire DOC personnel related to the implementation of the consent judgment. They would also likely not be required to operate within the bounds of the labor agreement currently in place between the city and the correctional officers’ union and would have the ability to negotiate a new contract with the union.

The DOC commissioner would likely still have some control over Rikers Island but would have the “powers granted to the receiver…suspended for the duration of the receivership,” according to the proposed receivership plan from the Legal Aid Society. However, the commissioner would be expected to “work closely with the receiver to facilitate the receiver’s ability to perform their duties.”