Queens criminal court will have just one Black man on the bench after state cuts judges

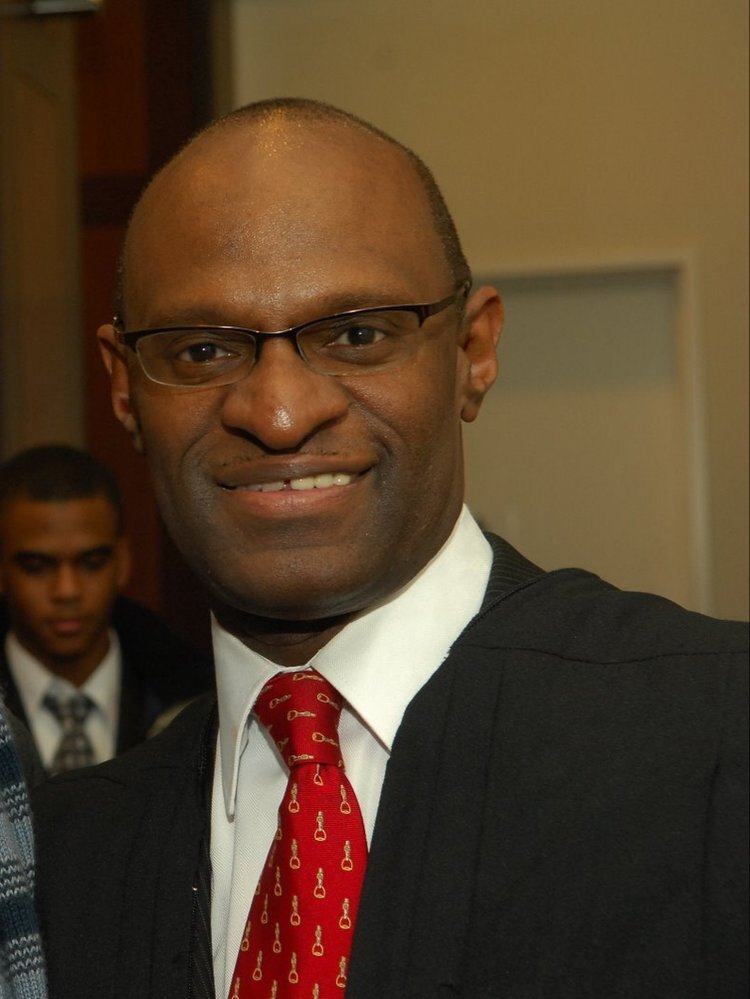

/Queens Supreme Court, Criminal Term Justice Kenneth Holder will be the only Black man on the bench in the county’s criminal court next year after two judges retire and another is forced out by the state. Eagle file photo

By David Brand

The criminal courthouse in the most diverse county in the United States will soon have just one Black man on the bench.

A state court system decision to cut ties with nearly every judge over 70 in New York will push out three Black judges who currently serve in Queens Supreme Court, Criminal Term at the end of the 2020. Justices Ronald Hollie and Leslie Leach have each decided to retire, while Justice Daniel Lewis is among 46 state judges denied recertification in an effort to trim the judiciary budget.

That will leave Justice Kenneth Holder as the only Black man presiding in a court where Black men make up the largest proportion of defendants.

Holder did not provide a response for this story, but several legal leaders and elected officials denounced the disparity. The move to push out older judges has only exposed long-standing issues affecting Black men throughout the legal system, they said.

“The dearth of Black judges, particularly men, is shameful,” said Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Erika Edwards, who leads an organization for Black judges called the Judicial Friends Association.

The Judicial Friends recently submitted a detailed report on institutional racism in the New York court system to the Office of Court Administration’s new Commission on Equal Justice in the Courts. The commission, led by former Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson, was formed to address systemic bias in the wake of nationwide demonstrations against racist police violence.

Black men and women account for about 14 percent of the state’s 1,291 judges, according to OCA data included in the Judicial Friends’ report. Edwards said the inequity in Queens is an example of the issues the organization is seeking to expose.

“This is what we’ve been talking about,” she said. “The importance of judges being elected in their communities, about more being appointed.”

A spokesperson for OCA said officials are aware of the Queens disparity and will consider “any possible options.”

With 2.3 million people, Queens is one of the largest counties in the United States and home to thousands of Black and African American professionals.

The lack of Black men on the criminal court bench next year in Queens is even more glaring given the borough’s reputation as the nation’s most diverse county, said attorney Jawan Finley, the president of Queens’ Macon B. Allen Black Bar Association

“The optics is reminiscent of a time from our not-so-distant past,” Finley said.

“There has always been a sense of racism within the criminal justice system in terms of the number of arrests and the harsh sentences imposed on Black and Brown men,” she continued. “We know that it is extremely important to have Black male jurists who can empathize with the many Black and Brown men that come through the criminal justice system.”

Black and African American people accounted for 38 percent of all Queens defendants in 2018, the highest proportion of any race or ethnicity, according to a report published last year by the Criminal Justice Agency, an organization that works with the state to provide defendant services.

About 34 percent of defendants were Latino, 13 percent were Asian and 12 percent were white that year, CJA found.

Finley said the judicial inequity reflects the obstacles throughout the justice system that can prevent Black men from rising through the ranks in prosecutors’ offices, law firms or public defender organizations — key avenues for becoming candidates for judgeships.

The Macon B. Allen Black Bar Association is focused on building “a pipeline from the bar to the bench with the hopes of creating a diverse judiciary and assuring that there will be no question about the fairness of the process,” Finley said.

The DA’s Office is a particularly important path to the criminal court bench in Queens. Holder, for example, was chief of the Narcotics Bureau before his election to a judgeship in 2006.

Few Black men have risen to prominent positions in the Queens DA’s office in recent years, however,

In September 2018, there were just 12 Black male lawyers working in the Queens District Attorney’s Office, and just one Black man among the top 12 positions, the Eagle reported last year. Executive ADA Jesse Sligh led the Special Prosecutions Division but retired earlier this year.

The Queens DA’s Office did not respond to requests for this story.

More Black attorneys, particularly women, have high-ranking roles under new DA Melinda Katz compared to her predecessor’s administration, but there are no Black men in executive positions, according to an employee who shared staff demographic information.

Still, the DA’s Office shouldn’t be the only route to the judiciary, said attorney Tim Rountree, the head of the Legal Aid Society’s Queens criminal defense unit.

Rountree said the reliance on prosecutors to fill the bench skews the justice system and precludes qualified lawyers in the criminal defense and public interest fields from becoming judges. The judiciary should reflect a diversity of backgrounds and experiences, he said.

“For far too long the bench in Queens has come from the Queens DA’s office,” he said. “This must change for real diversity.”

Black women are also underrepresented in the Queens judiciary, but a few hold powerful positions. Civil Supreme Court Administrative Judge Marguerite Grays and Criminal Court Supervising Judge Michelle Johnson, a November candidate for the state Supreme Court, are both Black.

Another state Supreme Court candidate, New York City Civil Court Judge Lance Evans, is also Black. He will likely serve in Civil Supreme next year, but Chief Judge Janet DiFiore could choose to assign him to the bench in Criminal Supreme Court.

“I would hope the Chief Judge, who does those assignments, makes the appropriate choice,” said Rep. Gregory Meeks, who, as head of the Queens County Democratic Party, has ultimate influence over judicial nominations. In heavily Democratic Queens, the nod from Meeks and the county party typically means a nominee can begin sizing their robes.

“I’m in no way happy or satisfied with the number of individuals [of color] who are on the bench,” Meeks said. “We need much more. We need more African American males and females, South Asians, Latinos.”

Since taking over the party leadership position in March 2019, Meeks has earned praise for nominating a diverse slate of judges and attorneys for Civil Court and Supreme Court nominations.

He is also a former Queens prosecutor and said he recognizes the importance of a diverse DA’s Office as a pipeline to the bench.

“There’s no denying that we’ve got work to do in Queens County,” he said. “We need to make sure Queens County, the most diverse borough in the country, is diverse in every way, and when I have the opportunity to recommend, nominate or influence in any way to make that so I will.”