Fired supers lose their jobs and their homes across NYC

/Carlos Zambrano (inset) was fired from his job as a Harlem superintendent after a new company purchased his building on West 116th Street. He faces eviction proceedings. Google Maps photo

By David Brand

For nearly 25 years, Carlos Zambrano took out the trash, patched up the leaks and fixed the boiler as a the superintendent of his apartment building on West 116th Street in Harlem.

That all changed in March, when a new LLC purchased the property and the management company New Holland Residences took over the building.

New Holland Residences fired Zambrano, along with several other superintendents at the nearby buildings it managed. The sudden termination was a double whammy for Zambrano — after taking away his job, New Holland commenced holdover proceedings that could lead to an eviction.

“These guys bought it in 2018 and they told me since I have a disability, they have a new program and they need guys to go around to the other buildings, to the next block,” said Zambrano, who has a leg problem that affects his mobility.

He could handle a few buildings on 116th Street, but he said he would struggle to move among New Holland buildings in various parts of the city, and so he was fired. Since then, he and his wife have struggled to earn enough money to get by.

“Our Con Edison bill is high and I don’t even know how I’m going to pay for it,” he said.

Zambrano isn’t alone. All across the city, property owners and managers fire non-unionized superintendents en masse when their companies purchase large building portfolios, said Sateesh Nori, the attorney-in-charge of the Queens Neighborhood Office of The Legal Aid Society.

“The whole portfolio will sell from one corporate landlord to another and as part of their revamping, they will fire everyone and bring their own people on, and have a management company to bring their own staff and a clean slate,” Nori said.

In lower density areas, like much of Queens, landlords who purchase or inherit a building end the often informal relationship that the previous owner had with the super — sometimes after decades, Nori said.

Carlos Zambrano was fired from his job as a Harlem superintendent after a new company purchased his building on West 116th Street. He faces eviction proceedings. Photo courtesy of Zambrano

“When your job and your housing are tied together, you’re twice as vulnerable to displacement and financial insecurity,” Nori said.

‘It doesn’t add up’

“If this is an emergency, please contact your super,” says the voice message on the general answering machine for New Holland Residence.

Zambrano said he still gets calls from tenants, including one woman who had a leak in her apartment late-Monday night.

“Tenants call me on nights and weekends,” Zambrano said. “It’s crazy because it’s a big building.”

New Holland manages dozens of properties in Northern Manhattan and Central Brooklyn. Scores of buildings across the city are connected to LLCs listed at 256 West 116th, site of New Holland Residences, according to building records. New Holland contracts with porters and handymen who service several buildings across the city, instead of in-house supers, tenants told the Eagle.

The company fired at least 15 superintendents,

Including Zambrano and his friend Eduardo Mejia, said attorney Kendall Wells of the New York Legal Assistance Group, who represents both men.

Mejia lives with his three children, wife and mother-in-law at an apartment on Morningside Avenue, inside one of the buildings where he worked as super for about six years. New Holland fired him in March and commenced holdover proceedings a few months later.

“I’m in a hard situation,” Mejia said. “My kids are 3, 9 and 12. I wanted everything to be fixed before school but now they’ve started school.”

If the family is evicted they will need a new place to live, as well as a new source of income.

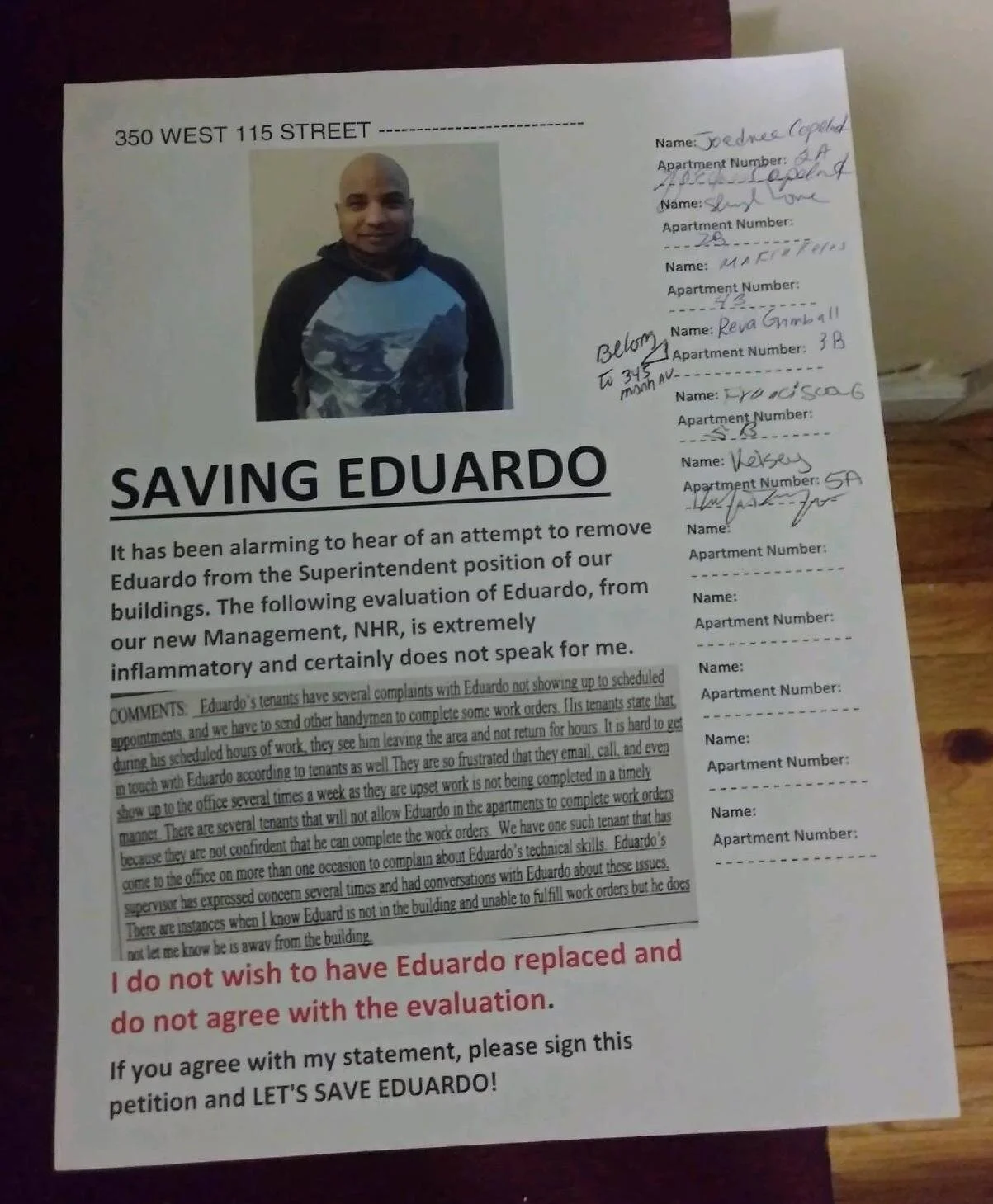

One of three petitions circulated and signed by tenants at buildings where eduardo mejia used to work as building super. photo courtesy of mejia

Zambrano said New Holland criticized his job performance in an evaluation before firing him. But one tenant, who asked not be identified because he fears retaliation from the management company, said Zambrano did good work and served a vital function in the community.

“Carlos is universally liked and respected,” the tenant said. “But that’s how supers work.”

“A big part of their value is they know the little kids, they know the teeangers that are messing around and they can tell them to cool it,” the tenant added. “They’re the cultural center of what’s going on and you definitely felt that absence.

Mejia received a similar “inflammatory evaluation that wasn’t accurate” as grounds for his firing, Wells said.

Like Zambrano, Mejia furnished letters of support signed by several tenants refuting the claims. Tenants also signed onto “Saving Eduardo” petitions at 345 Manhattan Ave., 6 Morningside Ave. and 350 West 115th St, where Eduardo worked.

“It doesn’t add up to be quite honest,” Wells said. “It’s ridiculous that just because a new management company takes over, they can fire someone who has worked there for years.”

a tenant’s flier criticizes new holland residences for the “unjust firing” of Carlos zambrano. photo courtesy of zambrano

A gap in tenant protections

New Holland Residences at first declined to provide comment for this story.

“You don’t know who I am. If you call me back I’m going to make sure you know about it,” said the person who answered the company’s office phone.

Later in the afternoon, David Schwartz, co-founder of New Holland’s parent company Sugar Hill Capital Partners called to say the company was “not in a position to talk about staffing or procedures or our policy.”

“At this stage we’re still trying to figure out how to size our staff in light of the impact of the New York legislation” on tenant protections, Schwartz continued. “Our goal is to maintain a good environment for our employees and to look out for the interest of our investors.”

The state’s landmark package of tenant protections that Schwartz referenced could play a role in compelling more super terminations, as landlords determine that cases against superintendents are easier to win than other proceedings, said Wells, the NYLAG Attorney.

“Landlords are a little scared and they’re defensive,” Wells said. “They’re trying to figure out how to proceed and super holdover cases can be difficult to win.”

Noori, from Legal Aid, said the superintendent-landlord relationship is considered an “employer-employee” relationship rather than a traditional landlord-tenant one, which gives the superintendents less standing in housing court.

There are ways that supers can defend themselves, however.

“The variable is, was the person a tenant before they became a super? And if they were, we would argue that the relationship reverts to a landlord-tenant relationship,” Nori said.

Some supers can also demonstrate that they were underpaid as part of their informal relationships with landlords and can show cause for compensation, Nori said. When the landlord attempts to evict, the super can claim retaliation, he added.

“Supers are not only working in the building, they’re part of the community,” Nori said. “It’s a real problem.”

Councilmember Robert Cornegy, chair of the Housing and Buildings Committee, said he will look into introducing protections for superintendents who are at risk of summary firings.

“When building supervisors lose their jobs, they’re not just out of work, but they’re out of a place to live,” Cornegy said. “There are no tenant protections for supers, because their housing is provided through their employment.”

Cornegy noted that supers are at particular risk when property owners buy large buildings or portfolios.

“These are men and women who have serviced buildings for many years, and they lose their job just because the building comes under new ownership,” he said.