Rikers receivership case sluggishly moves forward

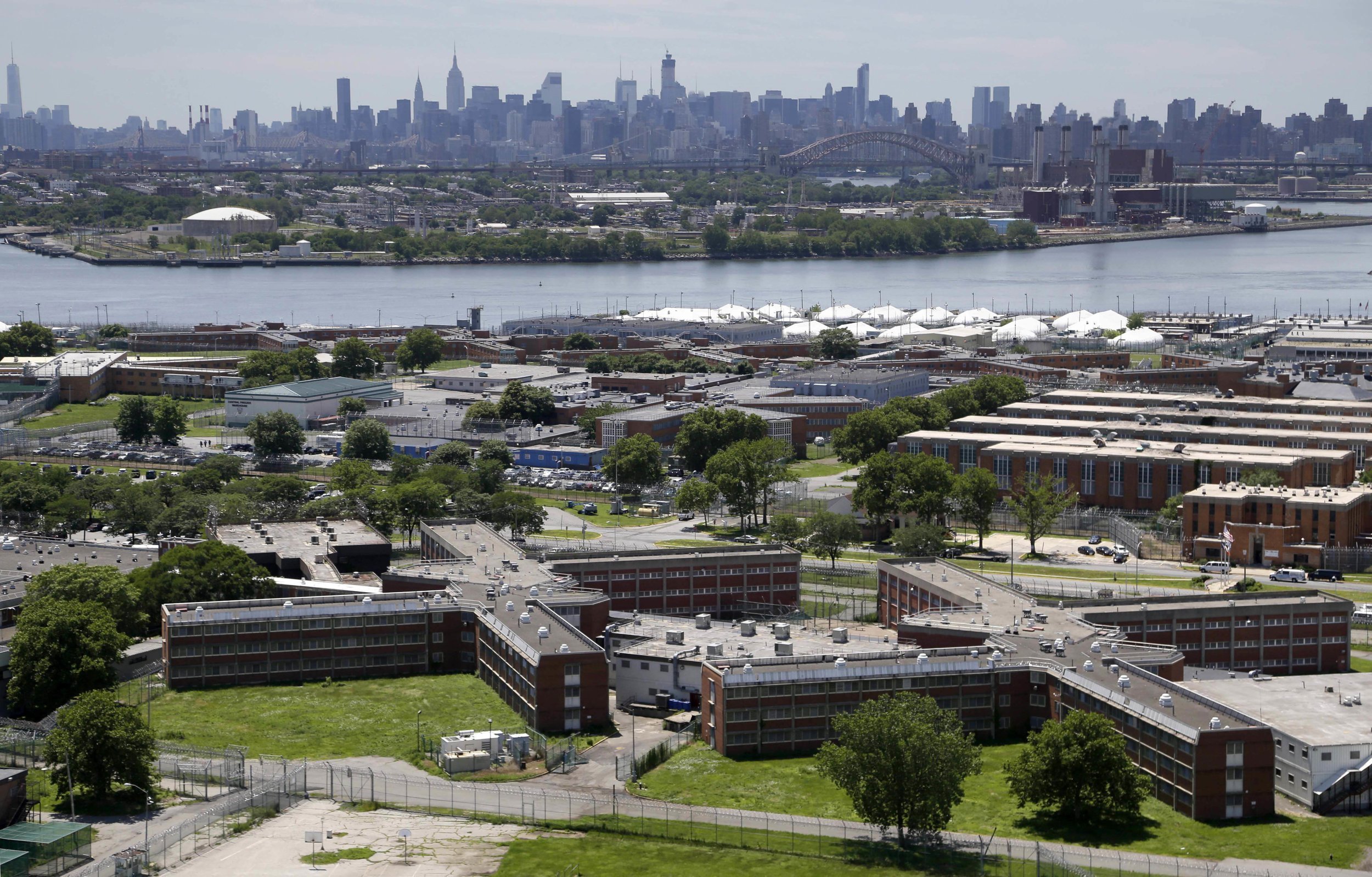

/The city’s Department of Correction on Tuesday appeared before the federal judge currently considering whether or not the city should be stripped of its control of Rikers Island. The case has been slow moving, the judge said, but a partial resolution may come toward the end of the year. AP file photo by Seth Wenig

By Jacob Kaye

For the first time in nearly seven months, the city’s Department of Correction on Tuesday appeared before the federal judge currently considering whether or not the city should be stripped of its control of Rikers Island, the troubled jail complex that has seen over two dozen deaths in the past two years.

While the judge, Laura Swain, noted several times the urgent need to address the ongoing and pervasive violence in the city’s jails, there was no major movement made on Tuesday toward deciding whether or not the city will remain in control of Rikers or instead have it given to a court-appointed authority known as a federal receiver.

Though Swain began the hearing in Manhattan federal court by saying that the “current risk of harm in the jails is as alarming as it is unacceptable,” there doesn’t appear to be a quick resolution to the receivership question in sight.

Even the judge acknowledged the slow movement toward the end of the receivership decision.

“Yes, we are in a long litigation process but the responsibility, the charge, the mission is one that is right every single day and needs to progress toward safety,” Swain said. “I demand and expect that of the parties that have lives in their care.”

The biggest decision to come out of Tuesday’s hearing was the schedule for upcoming hearings in the case, known as Nunez v. the City of New York.

Attorneys with the Legal Aid Society, which represents the plaintiffs in the case, and lawyers for the city – the defense – will appear before Swain on Sept. 25 and argue whether or not the city should be held in contempt for its alleged violations of the 2015 consent judgment stemming from the Nunez case.

Swain likely won’t make a decision on the contempt question until December, she said, noting that informing her decision would be a report from her appointed federal monitor on the conditions in the jails scheduled for Nov. 21.

Should Swain find the city in contempt, a new argument process over whether or not a receiver should be appointed – and what a receivership might look like – would begin.

“I would need to do much more focused thinking about what the right path is [for receivership] following a contempt finding,” Swain said.

If the judge were to make even a partial ruling in the case in late fall, it would come around a full year after the Legal Aid Society first officially filed for contempt and called on Swain to strip the city of its authority over Rikers.

In its November 2023 filing, the public defense firm claimed that the court was out of options – no other court order had or will get the city and its Department of Correction to comply with the consent judgment reached in Nunez, which ordered the DOC to make a number of changes to reduce violence on Rikers, primarily by reducing incidents in which officers use violence against detainees.

The over 100-page filing attempted to lay out the case for receivership, arguing that the DOC has “overwhelmingly” not complied with the heart of the consent judgment. Use of force incidents have continued, and the DOC hasn’t done much to hold staff accountable when they cross the line, the filing argued. The Legal Aid Society also argued that the DOC has generally failed to keep detainees safe on Rikers Island and that “the risk of severe harm in the jails is as imminent, if not more imminent, in the present moment as it was when the consent judgment was entered.”

“The levels of violence and brutality in the city jails that exist today were unimaginable when the consent judgment was entered in 2015, and the city has demonstrated through eight years of recalcitrance and defiance of court orders that it cannot and will not reform its unconstitutional practices,” Mary Lynne Werlwas, the director of the Prisoners’ Rights Project at The Legal Aid Society, said in a statement in November. “A receiver with the authority and mandate to make the difficult decisions the city will not is needed to secure the progress that two administrations and multiple Correction commissioners have all failed to achieve, and protect the constitutional rights of all people incarcerated in New York City jails.”

The city responded by arguing that it had not only made improvements to the jails, but that its new commissioner, Lynelle Maginley-Liddie, should be given an opportunity to reform the jails further.

The commissioner, who was appointed to the role by Mayor Eric Adams in December, took over the position from Louis Molina, who had largely spurned efforts for reform and oversight from the court’s monitor, Steve J. Martin.

Maginley-Liddie has largely been seen as a well-intentioned, reform-minded commissioner, whose appointment was celebrated by the monitor and Swain. On Tuesday, the monitor noted that since Maginley-Liddie’s appointment, the working relationship between the DOC and the monitoring team had vastly improved.

The city has mostly centered its argument against receivership on Maginley-Liddie’s shoulders.

Prior to the hearing on Tuesday, the mayor said that he was “not concerned at all” about receivership, which he vehemently opposes.

“I know we are moving in the right direction,” Adams said. “I am so excited about the commissioner who is there and what she is doing.”

But Maginley-Liddie is not the first reformer to take the role since the consent judgment was first put in place.

“Since the parties first entered into this consent decree almost a decade ago, conditions on Rikers Island have spiraled, and despite who runs the Department of Correction, the City is unwilling to make the fundamental changes needed to fix this morass,” the Legal Aid Society said in a statement after the hearing.

“Only an independent body such as a receiver, who is not bound by politics or other interests, can deliver on the wholesale change all incarcerated New Yorkers need and are constitutionally entitled to receive,” they added. “We look forward to addressing the court at the oral argument in September.”

What exactly a receivership may look like if Swain finds one necessary remains unclear.

In their initial filing, the Legal Aid Society called for a receiver that would assume a number of the DOC commissioner’s powers and responsibilities. The commissioner would be expected to “work closely with the receiver to facilitate the receiver’s ability to perform their duties,” according to the public defense firm.

Ordering a receiver to take charge at Rikers would be a major undertaking, and one that would likely require months to figure out in court.

While a number of advocates and elected officials, including Public Advocate Jumaane Williams and Comptroller Brad Lander, have called for a federal takeover of the jails, they’ve warned that a receiver shouldn’t be considered a cure all.

Though she’s largely a supporter of receivership, City Councilmember Sandy Nurse, who chairs the council’s Committee on Criminal Justice, told the Eagle earlier this month that there’s no guarantee the judicial order would make the jails safer.

“It's essentially a very big gamble,” Nurse told the Eagle. “If the city loses its ability to control its own jails, and situations continue to be horrible, particularly on Rikers, this can blow up in everyone's face.”

“On the other hand, if what is needed to cut through the current administration of our city jails is a federal takeover of them, then that's what has to happen,” she added.