'A long journey': Appellate court overturns Queens man’s 30-year-old murder conviction

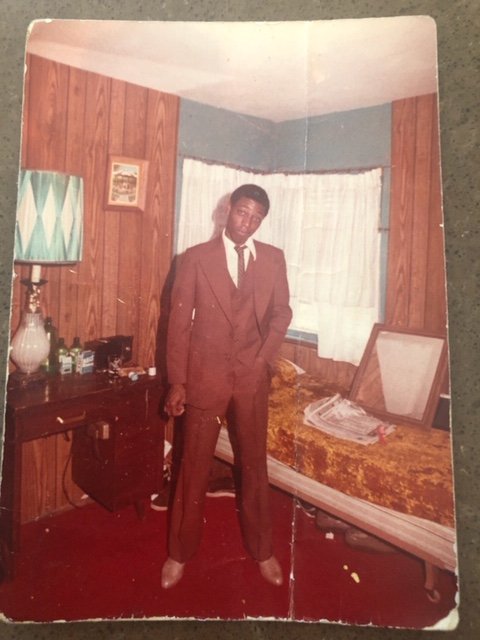

/Michael Robinson learned last week that an appellate court had overturned his 30-year-old murder conviction, which he spent 26 years in prison for despite his pleas of innocence. Photo via Legal Aid SocietY

By Jacob Kaye

For more than a quarter of a century, Michael Robinson looked for a way out of prison. Scouring through the law library, submitting Freedom of Information Act requests and working with attorneys, Robinson slowly began to crack open the case.

The former correctional officer from Queens found his way out in 2019, after being granted parole. But the murder that landed him in prison, the one that he had consistently said he didn’t commit, was still hanging over him.

He’d have to wait another three years before a court would formally recognize that he was wrongfully convicted.

That recognition came this month, after a panel of judges in the Appellate Division, Second Department overturned Robinson’s conviction, ruling that newly discovered DNA evidence, which was found by Robinson himself, would have likely changed the outcome of his 1993 trial had it been presented to the jury at the time. The case has now been sent back to Queens Supreme Court for a potential retrial or an outright overturning of Robinson’s conviction, which would end his 30-year fight once and for all.

The appellate court ruling reversed a decision issued by Queens Supreme Court Justice Stephen Knopf, who declined to vacate Robison’s conviction. Robinson’s motion was based on the newly uncovered DNA evidence, which shows that DNA material found beneath the victim’s fingernails is 78 trillion times more likely to match someone other than Robinson.

Though his legal sagas have been long and arduous, the ruling from the appellate court, which typically takes six to eight weeks to issue a decision, came only four weeks after the case was heard.

“I was actually not surprised [at the findings of the decision] because we were hoping for a good decision,” Robinson, 56, recently told the Eagle. “But it was shocking.”

“It just caught everybody off guard,” Robinson added. “We're all still trying to process it at this very moment, but it was a long-awaited decision that we've been looking for for 30-plus years.”

Wasted years

Robinson, who was raised in Springfield Gardens, was convicted in the killing of his estranged wife, Gwendolyn Samuels in 1993.

Prosecutors said that Robinson stabbed Samuels to death inside the Bayside home of Alveina Marchon, who employed Samuels as a home health aide.

The prosecution relied on the testimony of Marchon, who was 88 years old at the time and the only eyewitness to the murder. Despite giving inconsistent accounts of the murder – and later being found to be legally blind – Robinson was convicted and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison. He had just turned 26 years old.

Throughout his time in prison, Robinson said that he kept busy, looking for a way to prove that he had been wrongfully convicted.

He initially appealed the conviction but it was upheld. He then requested the federal government review the case, which they declined to do in 1999.

His first break didn’t come until 2013, when after submitting a FOIA request, he received a box. Among the items inside it was a police report that indicated that there was additional DNA evidence not presented at trial, including blood stains on Samuels’ sweater and hair and nail scrapings.

Acting without a lawyer, Robinson sought post-conviction DNA testing on the blood samples and blood stains. A judge rejected the motion without holding a hearing.

Robinson then obtained representation from the Legal Aid Society, which successfully appealed the case to the Appellate Division, Second Department, which sent the case back to the lower Queens court “for further proceedings to ascertain whether the subject DNA evidence exists and, if it does, for forensic DNA testing of that evidence.”

Another roadblock emerged – Robinson and his attorneys were told that the evidence they were looking for no longer existed. It had been lost when the building it was being held in sustained damage during Hurricane Sandy, they were told.

Front row: Legal Aid Criminal Appeals Bureau Attorney Harold Ferguson (left) and Michael Robinson. Back row, left to right: Legal Aid DNA Unit Attorneys Terri Rosenblatt, Jessica Goldthwaite and Jenny Cheung. File photo via Legal Aid Society

What followed was a series of hearings to determine whether or not the damaged evidence could still be tested safely and produce a reliable result. In the end, a judge ruled that the testing could go forward.

That’s when the Queens district attorney’s office informed the court that the evidence was not in the flooded facility. It was instead with the office of the chief medical examiner.

“We wasted two years on two hearings, based on a false premise,” said Harold Ferguson, a staff attorney with the Criminal Appeals Bureau at The Legal Aid Society.

The medical examiner then tested the evidence, finding that there was male DNA in the victim’s fingernail scrape. They then tested it against Robinson’s DNA and determined that it wasn’t conclusive enough to support overturning the conviction.

Robinson and Ferguson then got Cybergenetics, a private lab, to review the evidence. Their findings were far more conclusive.

The lab determined that the DNA suggested that it was 78 trillion times more likely that Robinson was not the killer, a finding the OCME, which conducted further testing, later agreed with. But prosecutors were still not on board, and said that they believed that the male DNA didn’t necessarily come from the murderer, Ferguson said.

“If it's inculpatory, it's absolute proof of guilt,” Ferguson told the Eagle. “But when it's exculpatory, the DA’s office takes the position, ‘Well, that doesn't mean anything, it could have come from anybody.’”

Knopf later denied Robinson’s motion to vacate his conviction.

In the appellate court decision, the judges pointed out what they believe to be a number of inconsistencies in the witness’ account of the perpetrator.

“No physical evidence linked the defendant to the crime,” the decision reads. “The only identity evidence offered by the People at trial was the testimony of a single eyewitness, Marchon, who was 88 years old at the time of the incident and suffered from significantly impaired vision.”

“Marchon’s description to the police of the perpetrator’s appearance was not conclusive and was, in part, more consistent with [the victim’s boyfriend at-the-time] Jermaine Robinson’s appearance,” they added. “Under the facts of the case, it would not have been unreasonable to conclude that Marchon confused Samuels’s estranged husband with her current boyfriend in making her identification to the police.”

A chance to move forward

The appellate decision sends the case back to the Queens trial court, where Queens District Attorney Melinda Katz will decide whether or not she wants to bring the charges against Robinson again and retry him. Should she choose not to, Robinson, who was released from parole last week following the decision, would be freed of the charges completely.

Robinson, who is currently living with family members in Springfield Gardens, said that while he and his family were relieved by the appellate decision, they are wary of getting ahead of themselves.

When Robinson first learned of the decision, he said he took a deep breath but didn’t celebrate. He’s been trying to take each day at a time.

“I wouldn't say that [I’m not concerned], but you also don't want to let these types of things overwhelm you,” he said. “I got a lot of people behind me supporting me and I'm the face of this. If I show that I'm breaking down or I can't handle it – it’s already going to be overwhelming on that day when we get to court.”

Michael Robinson before his 1993 conviction. File photo via Legal Aid Society

A spokesperson for the Queens district attorney said that prosecutors were “reviewing the appellate court’s decision” but declined to comment further.

When Katz was running for office in 2019, just as Robinson’s case was picking up steam, the Eagle asked the then-candidate about her plans to create a Conviction Integrity Unit and how it might review Robinson’s case specifically.

“While I cannot comment on specific cases that I'll be overseeing, cases like this are exactly why I plan to create a Conviction Integrity Unit,” Katz told the Eagle in 2019. “My first priority will be to review all the facts for cases that rely on a sole witness and make appropriate determinations based on the evidence."

Katz followed through on her promise to create the unit, which has since reviewed and submitted motions to overturn dozens of convictions. However, Robinson and Ferguson brought their case to the unit in 2020, shortly after it was created, and were denied.

Ferguson said that prosecutor Brad Leventhal – whose alleged prosecutorial misconduct has been at the center of several convictions overturned by the CIU – told the attorney and Robinson that the case could not be reviewed by the unit because of their active motion to overturn the conviction.

“That's another sore spot here,” Ferguson said. “He said that the Conviction Integrity Unit could not do any review if there was a pending 440 motion, and if we wanted the unit to review the case, we would have to withdraw the motion, which of course was ridiculous.”

“He knew we weren't going to do that,” Ferguson added. “So, it really wasn't a true offer.”

But with the motion now upheld by the appellate court, Robinson said he’s finally starting to see an end to the case that has hung over his head for more than half of his life.

“It's been a long journey,” Robinson said. “I'm just waiting to get over this last hump.”