Holden bill aims to bring back solitary

/City Councilmember Robert Holden introduced a bill last week that would bring back solitary confinement for 18- through 21-year-old detainees who commit multiple acts of violence in the city’s jails. File photo by John McCarten/City Council

By Jacob Kaye

A Queens lawmaker is looking to bring back solitary confinement for young adults who commit multiple acts of violence inside the city’s jails.

City Councilmember Robert Holden introduced a bill in the legislative body last week that would reintroduce punitive segregation – also known as solitary confinement – as a form of punishment for detainees between the ages of 18 and 21 who carry out multiple acts of violence while in custody and who have previously received counseling after committing violent acts.

A detainee would have a choice to enter into counseling or punitive segregation – the practice of locking an incarcerated person in a cell for 23 hours per day – if the violent offense is the first committed while in custody, according to the bill.

Solitary confinement for the age group was banned in 2016.

The bill has the backing of the Correctional Officers’ Benevolent Association, the union representing corrections officers, which blames the increased rate of violence in Rikers Island on the lack of segregated housing for the age group.

“If our City Council members truly believe that everyone in our facilities deserves to be safe, then we must retain the ability to separate violent offenders from non-violent offenders, otherwise known as punitive segregation,” Benny Boscio, the president of the union, said in a statement. “We thank Councilman Bob Holden for introducing this critical legislation and encourage all City Council members to support it, so together, we can save lives.”

The bill also has the support of Holden’s colleague, Queens Councilmember Joann Ariola, who says that she plans to sign on as a co-sponsor.

“We have to take measures both inside jail and outside to make sure that we make the city safe again, and we cannot put our corrections officers at risk, nor can we put other inmates at risk,” Ariola told the Eagle. “It is something that I think is necessary, because without consequence the activity will continue.”

The federal monitor’s most recent bi-annual report on the jail noted that violence in the jail has increased in the past year. The monitor noted that at the Robert N. Davoren Complex on Rikers Island that “[r]ates [of fights] for both 18-year-olds and young adults aged 19 to 21 were at or near all-time highs during the current Monitoring Period,” but added that the rate of violence in the complex increased for all age groups during the observed time.

The monitor said that the increase in violence is to be blamed on the crumbling jail facilities and poor management of corrections officers, not the lack of punitive segregation for the young adults.

However, Holden said that the reintroduction of the practice was necessary to stem the rise in violence in the city’s jails.

“Violent, lawless behavior can no longer be tolerated in our city, inside or outside of city jails,” Holden said. “Our corrections officers walk the toughest beat in the city: our jails, and they are being assaulted with impunity by inmates.”

Stanley Richards, the deputy chief executive officer at the Fortune Society and a former first deputy commissioner at the Department of Correction, said that the bill, if passed, will do little to curb violence in the jail.

“What we know, particularly with young people, is that extreme isolation doesn't work,” Richards told the Eagle. “We have evolved as a society that we understand that if our children don't follow the rules and are do something that violates a rule, and we do a timeout, and then they do it again – we don't stop doing the timeouts, we don't stop doing the conversations, we don't then go and say, ‘now you are banned to your room for 23 hours out of the day.’”

City Councilmember Tiffany Cabán, who campaigned on a platform of reforming the city’s criminal justice system, said that she was “absolutely opposed” to Holden’s bill.

“Either care about outcomes or you don't,” Cabán said. “The evidence is pretty clear – meaningful out of cell time, particularly with access to medical, mental and physical care, achieves better public safety outcomes than solitary confinement ever would.”

Queens City Councilmember Tiffany Cabán says they city should invest in mental health and other services in an effort to lower the rates of violence in the city’s jails. AP Photo/Mary Altaffer

The conversation around solitary confinement has recently become a war over words.

Holden, Mayor Eric Adams and the correctional officers’ union have all suggested punitive segregation and solitary confinement are different practices.

“Punitive segregation, not to be confused with solitary confinement, is a much-needed option for keeping order and stopping the violence against officers and inmates on Rikers Island,” Holden said in a statement regarding the bill.

When asked for clarification, a spokesperson for Holden said the difference between solitary and punitive segregation comes in the process – punitive segregation requires a judge’s decision.

Though Holden says the two practices are different, the city’s Board of Correction, on its website, says the terms are interchangeable. The Correctional Officers’ Benevolent Association also notes that the terms describe a similar type of removal of a detainee from the general jail population.

“‘Solitary confinement’ is not a term used by corrections professionals,” COBA’s website reads. “That term, and those like it, is a well chosen demonizing expression created by the prison reform movement geared at evoking a reaction. Many advocates of [punitive segregation] reform do not bother to define their terms, and conflate all types of segregation or isolation of incarcerated persons – whether for their own safety, that of others, or as punishment for violent behavior.”

Adams, whose office did not respond to request for comment, has also suggested the words describe different methods. In December, he announced that he would bring back punitive segregation, and, later, was upset when a group of then-incoming City Councilmembers referred to the practice as solitary confinement.

“For people to continue to say ‘Eric supports solitary confinement’ – that is just a lie,” Adams said in December. “I support punitive segregation. I am not going to be in a city where dangerous people assault innocent people, go to jail, and assault more people … If you are violent, you must be removed from [general] population so that you don’t inflict violence on other people.”

Reform advocates say there is no difference between the practices.

“Extreme 23-hour isolation that was the form of punitive [segregation], solitary confinement, which are all the same thing, is not the answer,” Richards said.

The practice of putting young people in solitary confinement was banned in the city’s jails in 2016 by former Mayor Bill de Blasio, who cited a number of scientific studies that suggested the practice had a debilitating effect on the age group’s brain development.

A 2020 report from the United Nations describes the practice of all solitary confinement – keeping detainees in a cell for 22 or more hours per day for more than 15 days – “could amount to torture.”

"These practices trigger and exacerbate psychological suffering, in particular in inmates who may have experienced previous trauma or have mental health conditions or psychosocial disabilities,” said Nils Melzer, the UN special rapporteur on torture in 2020.

The move to ban solitary confinement for the age group was the beginning of the city’s push to end the practice for all incarcerated individuals.

Under recently passed Board of Correction’s rules, the city was to implement the Risk Management Accountability System – a new form of segregated housing that would allow for more interaction between incarcerated people and increased programming – by Nov. 1, 2021. However, its roll out was delayed by de Blasio, who cited staffing shortages and the general crisis in the jail.

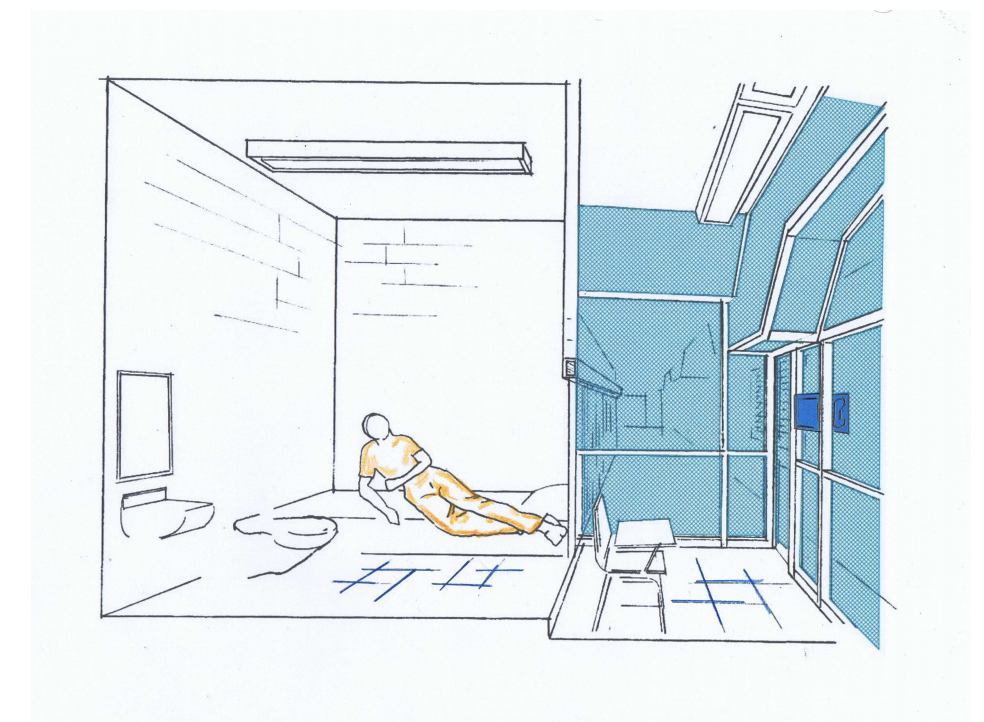

A rendering of a Risk Management Accountability System unit, a new segregated housing unit that has been delayed by the city since November. Rendering via BOC

The executive order delaying the introduction of the new units was recently extended by Adams and will remain in effect until the end of February.

DOC Commissioner Louis Molina told Board of Correction officials last week that he expects the new system to be in place by July 1.

“While I require additional time to see the vision through, I’m confident that the reforms we’re pushing will serve as a model for restorative housing across the country,” Molina said.