Western Queens schools welcome migrant students but say city has fallen short on support

/Schools that have welcomed a disproportionate number of migrant students this school year, like P.S. 76 in Long Island City, say the city has yet to provide the resources each school requires to meet the students’ needs. Eagle photo by Liz Rosenberg

By Liz Rosenberg

One of the most overcrowded school districts in the city is also home to some of the highest numbers of migrant students, many of whom have arrived to the city in the past six months.

While local school parents and staff have galvanized the school community to bring resources to the over 300 new students living in temporary housing now enrolled in Queens District 30 schools, they say delayed funding, red tape and the inability to hire additional staff has hampered their efforts to meet the many needs of the new students.

Nearly 6,000 students have entered New York City public schools since the beginning of the school year. Most of them are new English speakers from Venezuela or other Latin American countries who are living in city shelters or hotels. At nearly 2,000 new students, Queens has welcomed more migrant children into its school system than any other borough in the city.

While each student in the city’s school system requires a variety of supports, newly arrived students require even more. Families' needs range from daily hot meals to securing clean warm clothing for the winter.

In District 30, parents and school staff say that while they’ve embarked on several different efforts to meet the needs of the new students, institutional support from the city has been lagging. In some cases, the students – many of whom require bilingual instruction in Spanish – are sent to Queens schools without bilingual teachers on staff.

“Where are the policymakers,” said Whitney Toussaint, a parent of two who serves as the president of Community Education Council 30. “Where are the helpers? Where were the logistics people?”

District 30 in Western Queens has welcomed more migrant students than 80 percent of districts in the city, according to a recent report released by the city’s comptroller.

While shifts in the student population of a school district happen each year, this year has seen particularly drastic shifts in a number of school districts. Advocates say the city’s model for funding schools that accept new students has fallen short, especially when it comes to funding resources to support students for whom English is a new language and who have likely experienced interrupted learning and a great deal of trauma.

In the district – which covers Queensbridge, Dutch Kills, Sunnyside, Woodside, Ravenswood, Long Island City, Astoria, Ditmars, Steinway, Jackson Heights and East Elmhurst – already strapped for resources, Toussaint says the city should have planned better, placing students in schools where supports have already been put in place.

The issue isn’t contained to only District 30.

In a recent letter to Schools Chancellor David Banks, Comptroller Brad Lander said “reports of teachers using Google translate to communicate with newly arrived students is but a symptom of decades long inaction on attracting and retaining bilingual educators.”

While devoting time and energy to food and clothing drives has its own rewards, parents still wonder why these efforts are falling to them with little support from the Department of Education. And some wonder if this level of support is sustainable as even more families are predicted to enter District 30 schools before the end of the year.

Toussaint recently received an email from the Department of Education encouraging parents to volunteer or donate money to “Project Open Arms,” the city’s recently launched plan to support newly arrived migrant families.

Seeing the email struck a nerve, she said at a recent Panel for Education Policy meeting.

“We need resources from the city,” Toussaint said. “If y'all can't get it to us, reach out to someone from the state, the federal government. A lot of the families in our district are low income. They are already giving from the little they have to provide for families that have even less.”

Located in Long Island City across from the Ravenswood Generating Station, P.S. 76 in District 30 has received 23 new students in temporary housing since the start of the school year and school community members say they expect dozens more before the end of year.

The city recently sent the school $46,000 as part Project Open Arms that could be used to fill an after-school program funding gap they have been experiencing, or for other needs they’ve identified, but not to hire full-time staff. If they receive more students in the coming months, each student will bring in an additional $2,000 in Project Open Arms funds.

P.S. 76 also received some funds to directly support students in temporary housing.

However, bureaucratic systems for spending the funds have made it difficult to quickly get students what they need, according to school secretary Catherine Dyab.

“It’s ridiculous,” Dyab said.

For example, Dyab said because things like winter boots and clothes are not items DOE schools regularly buy, the school is required to create three bids to purchase the needed products.

“These kids came with the clothes on their back,” she said. “It's going to get cold soon, really cold, and they're not ready.”

Around 84 percent of P.S. 76 students come from families that are “facing economic hardship,” according to Department of Education standards. The school’s parent teacher association rarely has more than $10,000 to work with, but it is currently running several initiatives to provide for new families, including shoe and clothing drives.

Marisela Santos, a mother of four and vice president of the PTA, said she sees her own parents in the faces of new families.

“I feel connected to them because my parents came to the United States without a clue of what to do,” she said.

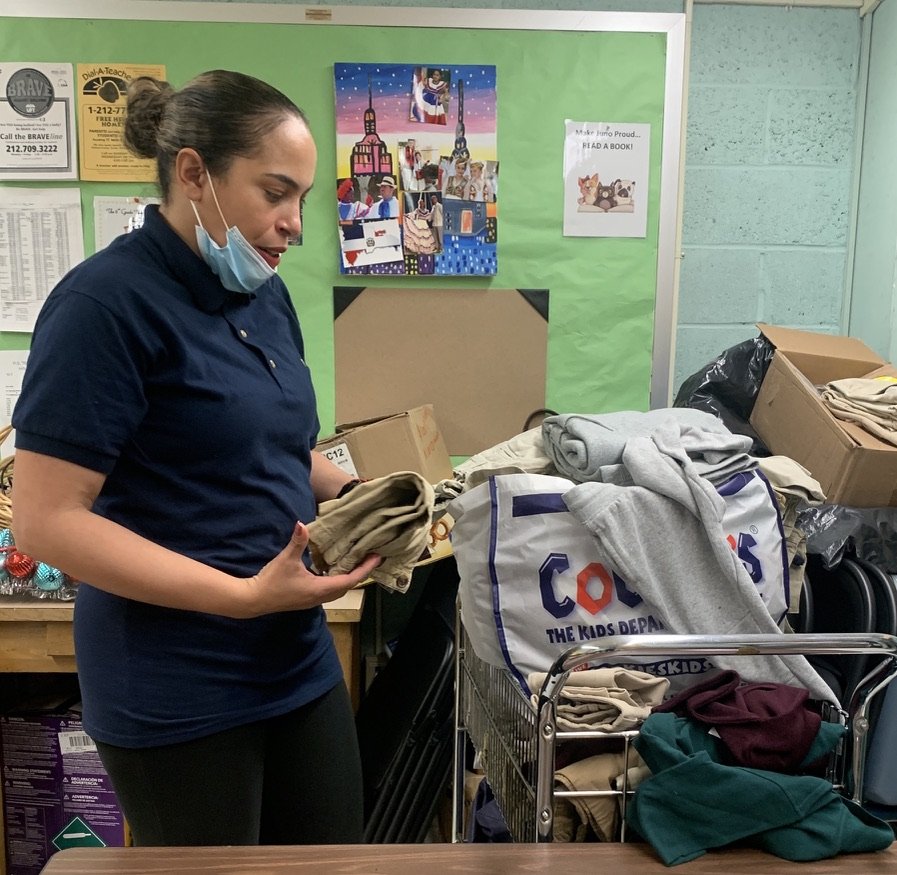

P.S. 76 parent Marisela Santos folds extra uniform pants that are kept in the PTA room for any students who need them. Eagle photo by Liz Rosenberg

On a recent afternoon, after folding donated school uniforms and organizing them by size, Santos dropped by the local food pantry to pick up flyers to distribute to families.

“I don't want them to feel hopeless. I want them to know that we are here,” Santos said. “Okay, maybe the city doesn’t remember you right now. But we are a strong community and any resources that we have, we’re going to share it with you.”

Despite their efforts, Santos said support from the PTA can only go so far. The school recently had to end its dual language program for fourth graders as a result of cuts made to the DOE in the city’s budget, she said. Santos has been told replacing the dual language staff at P.S.76 will be difficult at this point in the year.

“Now all these students are coming in and they have to be in dual language,” Santos said.

She and Dyab have been told to prepare for as many as 60 additional new students before the end of the year. But P.S. 76 will not be entitled to the $200,000 or more additional funding this number of students would have brought with them had they arrived before Oct. 31.

Jonathan Greenberg, another member of Community Education Council 30, says the system for new student funding is faulty. Schools that admit many students after the school year begins, “are always penalized in this system,” he said.

“Either their per-pupil funding is delayed until January, or there is no funding at all if students arrive after the register has been updated, which just happened on Oct. 31,” said Greenberg.

Per-pupil funding is $4,197 for elementary students and additional dollars are added for English language learners, students who live in poverty, special education students and other categories. English language learners add roughly $2,000 per student to school budgets. So far, the 23 new students at P.S. 76 have not been counted as English language learners on the school’s adjusted budget, according to DOE records.

The Department of Education’s Fair Student Funding Working Group, which is tasked with making school funding more equitable, recently issued a report that recommends increasing funding at schools like P.S. 76 with high concentrations of students in temporary housing and an influx of English language learners.

“New York City continues to welcome refugees and immigrants from all over the world creating greater levels of need for English language instruction to support these students,” the report says.

Greenberg said this year’s problems “are especially acute, but they're not new.”

“These schools need resources now,” he added.