A lifetime later, Queens man released from prison

/Robert Webster (right) was released from prison after serving 34 years of a 50 year to life sentence for a crime he says he never committed on Thursday, Oct. 20, 2022. Webster pictured at a pizza shop with one of his sisters, Ieishah Webster. Photo by Ana Montgomery-Neutze

By Jacob Kaye

The days and months leading up to Robert Webster’s hearing before the parole board were intense.

After serving over three decades in prison for an arson he says he never committed, the Queens man was getting an early – and somewhat unlikely – shot at release.

Now he had to decide whether or not he was going to take a risky gamble.

Over the summer, his attorneys submitted a motion – which was later granted by a Queens judge – to reduce Webster’s sentence from 50 years to life to the 34 years in prison he’d already served. The Queens district attorney’s office submitted a motion in support but said their stance on Webster’s innocence had not changed.

They still believed he was the 17-year-old boy who twice firebombed a home in Jamaica in 1987.

Suddenly granted his first chance to appear before a parole board, Webster had to decide whether he should confess to the arson and express remorse for the crime – as some advised him to do – or maintain his claim of innocence, just as he had done for decades. Choosing the latter could have resulted in a swift rejection by the board.

“One person told me the parole commissioners can detect bullshit,” Webster told the Eagle on Friday. “If I sat there and told them I did something I didn’t do, they would know.”

“I realized that I couldn’t do it,” he said. “I always felt that I had to tell my truth.”

On Thursday, Oct. 20, Webster was released from prison – a little more than a week before his 52nd birthday.

Webster’s release, his arrest, his conviction and his decades of incarceration highlight numerous aspects of the criminal justice system that advocates have long said are flawed.

He was prosecuted as a teenager during a time in the city’s and country’s history that took a particularly harsh posture toward criminal defendants, especially those accused of crimes related to drugs, like Webster. He was one of countless Black teens at the time to be slapped with an extreme sentence – an estimated 1,000 others like him continue to age in New York prisons. His arrest was built on questionable police work and alleged coercive confession tactics that were, and in some cases continue to be, all too common, he and his attorneys say. And his path to release was one that involved a number of twists and turns that exposed the bureaucratic and legal walls that prevent countless incarcerated people – innocent or otherwise – from attempting to right alleged wrongs.

In many ways, his release was highly unlikely.

“I never thought I'd be standing in front of Green Haven [Correctional Facility] without any handcuffs and shackles on, going into a caged van,” Webster said. “It’s a different feeling going down that road as a free man.”

Arrested at 17

The last time Webster was free was in the fall of 1987.

Around 4 a.m., on Nov. 10 of that year, a South Jamaica home belonging to a man named Arjune was attacked by two men throwing Molotov cocktails. The firebombing came several hours after Arjune, who did not have a last name, was believed to have called the police to report two alleged drug dealers standing on the corner of Inwood Street and 107th Avenue where he lived.

Webster was asleep at his mother’s house nearby, he said.

Arjun joined police on a search through the neighborhood and identified 27-year-old Claude Johnson as one of the two perpetrators. Johnson, who was arrested, would go on to be sentenced to 25 years to life in prison. He was released in 2020.

Two hours after the arrest, Arjune’s house was firebombed again. The man initially told police that he had not seen the perpetrators, according to records of the interaction.

Unaware of the arson, Webster was walking near Inwood and Pinegrove Streets the next day with his cousin, he said. Two NYPD officers stopped them and asked Webster to get in their car and come help them identify a rape suspect. Though he had not witnessed a rape, Webster told the Eagle last year that he was “naive and scared,” and told the officers he would help.

The officers instead took Webster to Arjune’s house, where his nephew, Herrick Khan, was waiting. Khan identified Webster as one of the people who tossed the Molotov cocktails into his house.

Webster, at 17 years old, was arrested. The teenager was sent to Rikers Island to await trial.

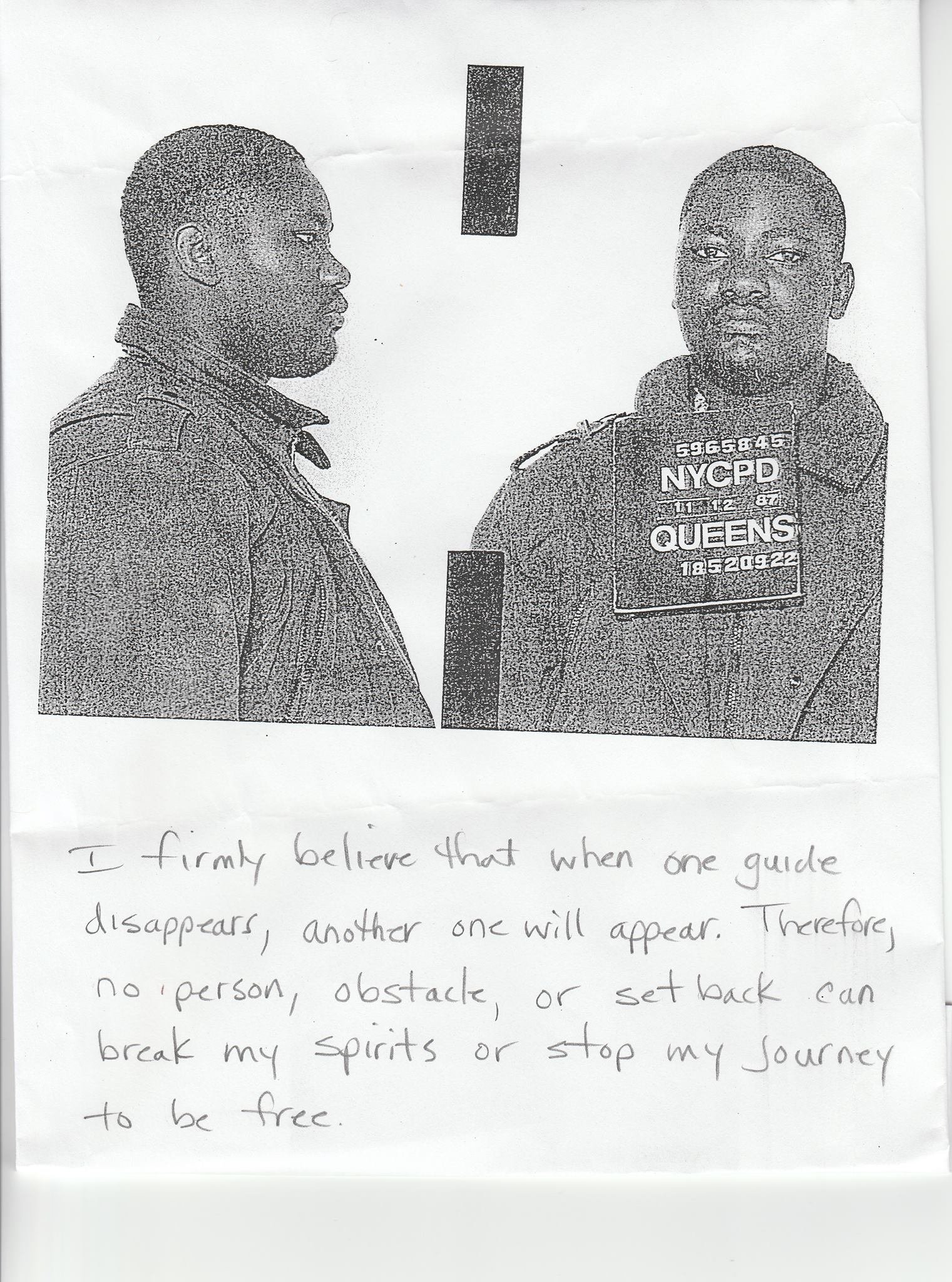

Robert Webster was arrest at the age of 17 for two arsons he says he didn’t commit. Photo via Robert Webster Freedom Project/Facebook

Beyond the identification made by Arjune – who also made a number of identifications he later recanted – there was no evidence linking Webster to the crime.

In February 1988, while Webster was detained in the city’s jail, police officer Edward Byrne, who was stationed outside of Arjune’s house to guard against future attacks, was shot to death in what was believed to be a retaliatory killing.

Despite being behind bars at the time of the killing, Byrne’s murder was the catalyst for Webster’s stiff sentence.

During Webster's trial, former Queens Supreme Court Justice Thomas A. Demakos said that the crimes “remind me of the drug kingpins in South America who, by their killing of their judges and their prosecutors, have injected so much fear in their community that they are practically immune from prosecution and here in our own community, we've had the killing of a witness to a drug transaction and we've even had the killing of a police officer who was guarding a witness...and we have the same thing here,” according to court documents.

Webster was sentenced to two consecutive 25-year-to-life terms, the maximum for the charges.

A path to release

In the early years of his incarceration, Webster was shuffled around between prisons. He eventually would come to spend the majority of his sentence in Green Haven, a maximum security complex in Dutchess County.

He believed early on that he would be quickly granted the opportunity to appeal his conviction. But as the years went on, he pivoted toward attempting to appeal his sentence. Though Webster petitioned several courts and attempted to take several legal avenues to get his case before a judge – both with and without the aid of an attorney – all ended up failing.

“The courts should have been more readily accessible,” said Steve Zeidman, the director of the Criminal Defense Clinic at the CUNY School of Law and one of Webster’s attorneys representing him in his separate case for clemency. “[New York State doesn’t] have any kind of in-the-interest-of-justice provision, which is sorely lacking.”

While several states and jurisdictions outside of New York currently have laws on the books that allow incarcerated people to petition a court to review their sentence, there is no such provision in the Empire State.

The Second Look bill, which would allow judges to review an incarcerated person’s sentence, was introduced at the start of this year in the state legislature but never made it out of committee.

“It's incredible to me, in light of the fact that we have neuroscience talking about the diminished culpability of youth and the inherent capacity of youth to change…and yet, New York State, at the legislative level as well as in the judiciary, has turned a blind eye to it,” Zeidman said.

Without any clear pathway to release, his efforts to find one began to slow as Webster got older and as the defeats continued to mount, he said.

His efforts never ceased entirely, but facing the prospect of growing up, living as an adult, aging and dying in prison, Webster decided to stay busy.

He became the first person in his family to earn a college degree, he studied business and computers, worked as a teacher’s assistant, built furniture and served as the vice president of a nonprofit organization.

Robert Webster became the first person in his family to graduate from college. Photo via Webster’s clemency application

His hope for his release didn’t return in earnest until 2021, when Webster submitted a clemency application to the governor.

Not long after submitting the application, Governor Kathy Hochul announced that she’d be reforming the way her office reviews and grants pardons and sentence commutations, the two clemency actions a governor can take – many of the reforms have yet to be enacted.

With the application for clemency pending, Webster also began exploring a different path to release – submitting a motion for a sentence reduction under the state’s recently passed Raise the Age laws.

The motion gained the support of Queens District Attorney Melinda Katz, whose office submitted a motion arguing that “justice [would be] best served by re-sentencing.”

In July, Webster appeared before Queens Supreme Court Justice Peter Vallone, who quickly granted the motion, allowing the Queens man the opportunity to appear before a parole board 20 years before he was originally scheduled to.

Vallone made no indication he believed Webster was innocent.

Webster’s hearing before the parole board was held on Sept. 28, a relatively quick turnaround for a board that is not fully staffed.

Webster said that during the hearing, one of the commissioners asked him why he thought police arrested him and not someone else.

“All I could say was, ‘I've been thinking about that for the last 34 years,’” he said. “Then she asked me if [the prosecutors] offered me a cop out, and I told her, ‘Yeah, 15-to-life,’ and she asked me why I didn’t take it and I said, ‘Because I’m innocent, ma’am.’”

“Then she asked me if I would take it now,” he added. “And I said no, because I’m innocent.”

Webster was approved for release by the board the next day. He was told he’d be sent home in about a month.

“If somebody has been maintaining their innocence for 34 years, in particular in a situation where there's all sorts of evidence to point to it, the idea that the parole board might hold that against you is ludicrous,” Zeidman said. “Was [his release] improbable and unlikely? It was. But that just highlights the problem with the whole criminal legal system.”

‘I’m going to be alright’

The month between the parole board’s decision and Webster’s actual release left him feeling conflicted, he said. While he was relieved that he’d soon leave prison, he said that he also began to feel a sense of “survivor's guilt.”

“You have a lot of men in there who are stuck – and I was one of them,” he said. “It's a hard thing for a lot of guys, seeing somebody just walk out and they think it should be them or that they deserve an opportunity.”

“I feel bad for a lot of guys that are still in there but I worked hard for this,” he added. “And a lot of people believed in me.”

Webster walked out of Green Haven on Thursday and was greeted by a number of family members and friends.

He jumped into a car, where new clothes were waiting for him. The group drove south toward New York City. They stopped at a pizza shop nearby. He went to his cousin’s barber shop. He ate dinner at Cabana, a restaurant on Austin Street in Forest Hills – a 30 minute walk from where he was sentenced to prison 34 years ago. He got a phone, which he is still learning to use. He went to his mother’s house in Brooklyn.

Robert Webster (right) gets a haircut from his cousin, Dwayne Curry, hours after being released from prison. The Queens man served 34 years of a 50 year to life sentence for a crime he says he never committed. Photo by Ana Montgomery-Neutze

Speaking to the Eagle about 24 hours after he’d been released, Webster said that the most exciting and scariest aspect of being back home is the same – his freedom, which he’s experiencing for the first time as a man with a number of gray hairs poking through his goatee.

“Being safe in your own skin – being safe and confident to just go somewhere,” Webster said. “Getting that confidence to move by yourself.”

Webster’s sister, Vanessa Webster, said she’s most looking forward to having her brother physically present at family gatherings, like the upcoming birthday celebration he’s about to have. Speaking with him on the phone is one thing, she said, having everyone together at the same time is another. She was 14 years old when her brother was arrested.

“I feel like a kid again, like I'm back in Queens,” she told the Eagle. “It feels like a dream – is this the 80s or the 90s, or is it 2022?”

Though he’s grateful to now be able to spend time with his mother, cousins and sisters, he misses his father, who died in 2017.

“I was a 17-year-old kid going into this situation and it weighed heavy on my father,” he said. “I had a special connection with my father. He’s not here to see this.”

Webster will be on parole for the remainder of his life, though he’ll have an opportunity every three years to petition its end.

He said that he’s hoping to find a job in criminal justice, either working as a case worker helping formerly incarcerated people find their footing, or as an advocate, pushing for reforms that may have changed the outcome of his teenage and adult life had they been enacted when he was a child.

“'I’m so happy for Robert as an individual – 34 years, he grew up in prison into a remarkable person, all credit to him and his peers,” Zeidman said. “But there are other Robert Websters in state prison.”

While much about Webster’s future – one which, for decades, never seemed like a possibility – is uncertain, he knows that nearly everything he does will be a “learning process.”

“It’s not an easy thing, and I know I’m probably affected by spending 35 years of my life in prison,” he added. “But I'm going to be alright.”