Queens man seeks clemency

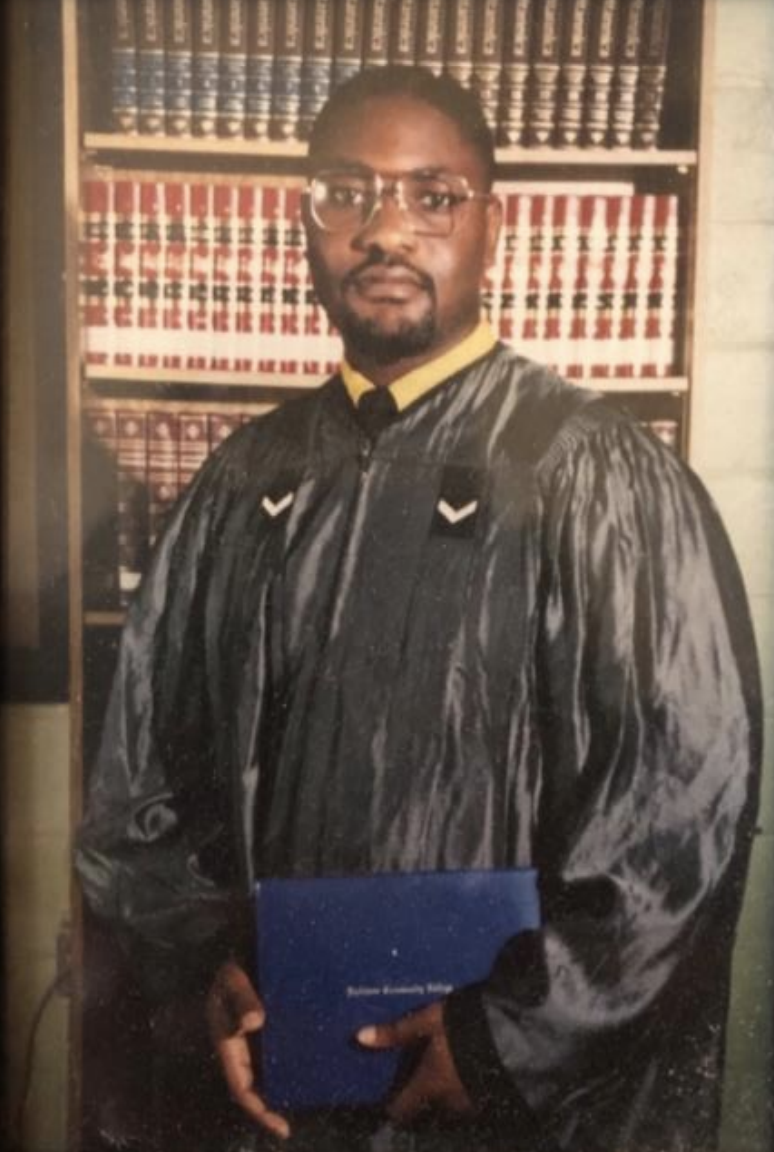

/Queens-raised Robert Webster was charged and sentenced to 50-years-to-life in prison for a crime he says he didn’t commit and is now seeking clemency from Governor Kathy Hochul. Photo via Webster

By Jacob Kaye

Robert Webster has done more than most over the past three decades.

He’s earned a liberal arts degree, studied business and computers, been a teacher’s assistant, built furniture and served as the vice president of a nonprofit organization. A bit of a renaissance man, he’s done it all while serving a fifty-year sentence in prison for two arsons he says he didn’t commit.

Webster was 17 years old when two NYPD officers arrested him in South Jamaica. He was accused of twice fire bombing an Inwood Street house belonging to a man who had previously called the police on two alleged drug dealers doing business on the block the day of the arsons.

After Webster’s arrest, a police officer who was stationed outside of the attacked home, owned by Arjune, who did not use a last name, was shot to death. The shooting, at the time, was believed to be connected to the drug dealing and arson, and may have had an influence over the 17-year-old’s half-century sentence, Webster’s attorney says.

Now, at the age of 51 with nearly 20 years of his sentence left to serve, Webster is awaiting Governor Kathy Hochul’s decision on his application for clemency.

“Right now I’m hopeful – I'm really, really hopeful,” Webster told the Eagle. “Everything that I'm doing right now, the petition and everything, is giving a lot of people, my family, my friends, hope.”

A Stiff Sentence

On Nov. 9, 1987, two calls were made to the NYPD to report two alleged drug dealers standing on the corner of Inwood Street and 107th Avenue. Following the second call, believed to be made by Arjune, one of the two men on the corner was arrested.

Webster says he was in his mother’s Queens home sleeping around 4 a.m., the following day, when Arjune’s South Jamaica house was assaulted by two men throwing Molotov cocktails, which caused minimal damage. Arjune told police that both of the perpetrators were Black men.

The South Jamaica man and police canvassed the neighborhood and arrested 27-year-old Claude Johnson, who would go on to be sentenced to 25 years in prison – Johnson was released in 2020.

Two hours later, four men drove up to the house in a beige Chevrolet and tossed three Molotov cocktails at Arjune’s home. Arjune told police that he had not seen the perpetrators, according to records of the interaction.

The next day, two NYPD officers stopped Webster, who was walking near Inwood Street and Pinegrove Street with his cousin, and asked him to get in their car and help them identify the perpetrator of a rape. Though he had not witnessed a rape, Webster says that he was “naive and scared,” and told the officers he would help.

However, the officers took Webster to Arjune’s house, where his nephew, Herrick Khan, was waiting.

“[Khan] said adamantly, no, it wasn't me, and they let me go. I got out of the car, walked up 107th towards Pinegrove, trying to find my cousin again, and then, at that point, they approached me again,” Webster said. “They had Khan in the backseat and now, he's saying I am the one that fire bombed his uncle's house. They read me my rights and they took me to the precinct.”

According to Webster, while at the precinct, police officers swapped his charcoal jacket with a black jacket for his mugshot. The black jacket they placed on him matched that of the description initially given by Arjune.

In February 1988, while Webster was in Rikers Island awaiting his trial, police officer Edward Byrne was stationed outside of Arjune’s house and shot to death.

During Webster's trial, Queens Supreme Court Justice Thomas A. Demakos said that the crimes “remind me of the drug kingpins in South America who, by their killing of their judges and their prosecutors, have injected so much fear in their community that they are practically immune from prosecution and here in our own community, we've had the killing of a witness to a drug transaction and we've even had the killing of a police officer who was guarding a witness...and we have the same thing here,” according to court documents.

Webster was sentenced to two consecutive 25-year-to-life terms, the maximum for the charges.

‘I couldn’t see 50 years ahead of me’

Webster and his attorneys say there were multiple issues with Webster’s arrest, trial and sentencing – all of which point to his innocence.

Arjune, on multiple occasions, misidentified people throughout both Webster and Johnson’s arrests and trials. Evidence that would show police officers swapped Webster’s jacket was not presented at trial. And Webster’s mother and girlfriend, both of whom would have testified to his alibi the night of the arsons, were not able to give testimony at trial.

However, it’s not his alleged innocence that they say warrants clemency.

“Even if Robert Webster was guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, he merits clemency,” said Steve Zeidman, Webster’s attorney and director of the Criminal Defense Clinic at the CUNY School of Law. “That's based on the age he was when he was sentenced, the insanity of the length of his sentence and all that he has done and achieved over his 30-plus years in prison.”

Webster said that his perspective on his time in prison, which has amounted to his entire adult life, has changed over time. He felt hopeful his conviction would be overturned in the years immediately following it, though his appeals filed in the case were unsuccessful.

Even when he began to accept his sentence, Webster said that he still had difficulty grasping what his future would look like.

“I went from being a teenage kid, free on the street, to being a teenage kid locked up in an adult prison with 50-years-to-life,” he said. “I couldn't see 50 years ahead of me.”

While in prison — he’s served most of his sentence at Green Haven Correctional Facility – Webster became the first person in his family to earn a college degree. He discovered a love for teaching and has held multiple jobs.

Webster’s sister, Vanessa Webster, was 14 years old when her brother was arrested. Throughout the years, Webster has been able to call in to family gatherings and family and friends have often been able to make the trip upstate to see him in-person. Vanessa Webster’s son, who is now 21, has also been able to forge a “great relationship” with her brother, she said.

Still, Vanessa Webster, who works as a parole officer, said there were still barriers to connecting that have plagued the family for the past 30 years.

“It gets hard because I’m out here living my life but he’s living his life too, behind bars and there’s no real connection,” she said. “Of course, I can make a visit or have phone calls, but it’s no real interaction.”

“That’s my brother – I’ve been away from him for over 30 years,” she added. “I don’t really know him as an adult…I’m learning what his habits are as an adult but I knew him when he was a kid. It’s amazing. I have to support him in any way that I can but it’s mind boggling.”

In December, Hochul granted 10 clemencies – nine of them pardons and one of them a sentence commutation. Advocates have, for years, called on the governor and her predecessor to take more action when it comes to clemency, an action only the state’s top executive can take.

Clemencies are typically granted around the holidays or other special occasions – former Governor Andrew Cuomo granted a handful on his way out of office last year. In December, Hochul committed to creating an advisory panel to review applications and to grant clemencies on a rolling basis.

“I am much more optimistic and thrilled to hear the idea of clemency on an ongoing, rolling basis than I am at the advisory panel,” Zeidman said. “I think the only reason that governors want advisory panels is to give them a little bit of political cover. I don't know what extra guidance some advisory panel that’s going to meet a couple times a year could do. Instead, you have dedicated staff in your counsel's office who do this on a regular basis.”

“At least it's a recognition on her part that something has to be done,” he added. “She didn't ignore it, I give her credit for that.”

Even with the reforms, Webster said he feels like he’s in a state of limbo waiting to hear whether or not his sentence will be commuted and whether or not he’ll get that “feeling of ownership over my life,” he wrote in his clemency application.

His sister said the prospect of his release and getting her hopes up is “scary.” Zeidman said that he can’t “imagine how brutal [the waiting period] is.” But Webster said he’s pacing himself.

“This is like a marathon – I've been through court denials and all that, so I know what it's like to be rejected,” Webster said. “But I also know what it feels like to be resilient, and to just keep on going.”