Gilded Age labor struggles and how Steinway & Sons moved to Astoria

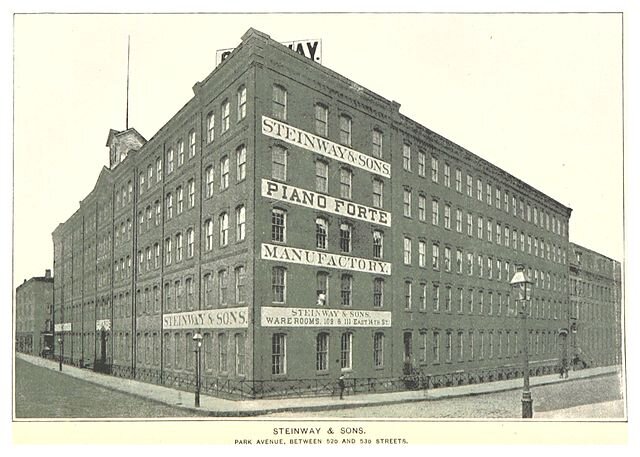

/Before moving to Astoria, Steinway & Sons had a factory in midtown Manhattan. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

By Prameet Kumar

Taking a stroll in western Queens, a name that appears again and again is “Steinway.” There’s Steinway Street and the Steinway Street subway station. People may know that the “Steinway” in these names is a reference to Steinway & Sons, the renowned piano manufacturing company whose products are synonymous with concert grand pianos. Steinway & Sons still has a functioning factory in the neighborhood, employing hundreds of workers.

But how did Steinway & Sons, which was founded in Manhattan, end up in Astoria? The answer to that question can surprisingly be found in the historical labor relationship between Steinway & Sons and the workers it employed in the late nineteenth century. The answer is also tied up in the greater history of the American labor struggle, particularly the emerging union and eight-hour work day workers’ movements of Gilded Age America.

Foundations and Growth of Steinway & Sons

Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg, the founder of Steinway & Sons, was born in northwest Germany. It was there that he first started a piano business in 1835, making up to two pianos a month at home. In 1850, Heinrich moved his family from Germany to New York. Already familiar with piano making, Heinrich and his sons went to work for the finest New York piano manufactures to learn the latest methods of production.

Three years later, on March 5, 1853, they decided to start their own piano manufacturing company in a small rented building on Varick Street, naming it “Steinway & Sons.”

“They appear to have thought that anglicizing their name would improve sales,” historian Richard K. Lieberman wrote in his 1995 history of the firm Steinway & Sons. They sold eleven pianos in their first year of business, all handmade by the family. The next year, they hired their first five employees and moved to a larger building on Walker Street.

The big break for Steinway & Sons came during the 1855 American Institute Fair held at the New York Crystal Palace, at which the firm exhibited one of its pianos. A reporter for Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper raved, “The Steinway square piano arrived at its present state of perfection, upon which it seems impossible to improve.” This positive press led Steinway’s sales to skyrocket from 74 pianos in 1854 to 208 pianos in 1856.

The popularity of Steinway’s pianos was so strong during this time that sales were able to withstand the panic of 1857, a national economic collapse triggered by railroad bond defaults and the failure of major financial institutions. New York, which was America’s financial capital, was hit especially hard by the panic. Thousands of businesses went bankrupt, and unemployment soared. These unemployed workers demanded government action, including at a rally of 4,000 people at Tompkins Square.

The experience of Steinway employees during the panic of 1857 could not have been more different from that of these unemployed workers. While the nation reeled from financial ruin, Steinway “felt invulnerable and rehired its eighty workers within the year – this at a time when most piano factories had fewer than thirty workers. Steinway not only prospered but, in 1857, during the worst depression in antebellum America, shipped more pianos (413) than it had in all the previous years combined,” Lieberman wrote. Not only did Steinway workers have secure jobs during this turbulent time, but they were paid relatively well in those jobs. While the average annual income of industrial workers was $300, even the lowest paid Steinway employees earned more than $400.

With sales booming, Steinway quickly outgrew its Walker Street factory. The firm purchased a site and built a new facility between Park and Lexington Avenues from 52nd to 53rd Street. “In a remarkably short period of time, between 5 March 1853, when they went into business and 1 April 1860, when they opened their new factory, the Steinway family had triumphed in America,” Lieberman wrote. The firm was successful beyond Heinrich’s expectations when he was making two pianos a month at his home in Germany; it now employed 350 workers and produced up to 35 pianos a week in New York.

The Piano Makers’ Union

As Steinway was finding success, its workers endeavored to partake in a greater share of the spoils, including through the unionization of the workforce. But the American judicial system had looked unfavorably upon this kind of worker activism.

In New York, the legislature enshrined anti-union sentiment into law in 1829, criminalizing any labor conspiracy “injurious to the public health, to public morals, or to trade or commerce.” In 1835, in the New York case People v. Fisher, the state upheld the legislature’s 1829 statute and ruled that striking shoemakers in the town of Geneva were acting in a manner injurious to trade and commerce. Legal historian Wythe Holt wrote that, in New York, “the courts and the law remained staunchly and overtly on the side of the employers.” It took until 1870 for the legislature to enact a statute overturning People v. Fisher and allowing workers to take collective actions. In the 1880 case Johnston Harvester Co. v. Meinhardt, the New York Supreme Court upheld this statute as long as union members showed “no sufficient evidence of violence, force or intimidation or coercion.”

The Steinway family struggled for years in their efforts to control workers’ unionization efforts. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The first major unionization effort among New York piano manufacturing employees took place in 1859, when 250 German piano workers (representing about one-fifth of the city’s total piano manufacturing workforce) formed a union called the “United Pianoforte Makers.”

During a United Pianoforte Makers strike against two manufacturers Bacon and Raven, the union passed a resolution that stated “that we look with proud satisfaction on the conduct of the Germans connected with the above strike, showing themselves second to none in manly resentment of insults received, and in the self-sacrificing spirit they have manifested in resisting a reduction of wages.”

In April 1859, the Herald published a long list of ongoing strikes and demands in the city, which included a “pianoforte makers” strike for 10 to 25 percent increase in wages from their current $10 to $16 per week. Even in its early days, this union was advanced enough to strike in an effort to gain union recognition and protest the firing of workers who were union members. It also employed such sufficiently advanced tactics as to “strike singly, one after the other, and thus enable the non-strikers to support those out on strike” and to financially support other unions that were on strike.

Seeing the writing on the wall and recognizing the danger that unions could pose to management control of Steinway, Heinrich’s son William suggested the formation of a company union, a union that would be affiliated with the employer and therefore not independent. But the idea “was quickly rejected by the workers based on the belief that their skills allows them to gain concessions from management and that Steinway's plan was not in the worker's interests.”

1864 Strike for Better Wages

Although Steinway weathered the panic of 1857 well, the Civil War years of the early 1860s took their financial toll. Piano manufacturers dealt with the loss of the Southern market and the limited supply of raw materials like lumber and metal. Meanwhile, workers faced inflationary prices on all goods. As a result of wartime deficit financing, the consumer price index in the North rose 75 percent from 1860 to 1865, while real wages in the North decreased 18 percent during the same time period. In the manufacturing sector, wages fell from $1.30 a day in 1860 to 97 cents a day in 1864.

The layoffs followed.

“In the summer of 1861 some thirty thousand people roamed the streets of New York City looking for work. At Steinway & Sons, pay cuts and layoffs occurred in every department; only the office clerks, salesmen, and foremen were unaffected,” Lieberman wrote. It was in this economic atmosphere that piano manufacturing workers, including those at Steinway, made another major push for better wages.

By 1863, the smaller German United Pianoforte Makers union gave way to a larger union of 3,000 New York piano workers called the Piano Makers’ Union. In October, this new union presented employers with a strong set of demands, including “a 25 percent pay raise, the right to review all firings, 100 percent union membership of workers, full employment throughout the year and weekly inspection of the factory ledgers.”

In response to these union demands and piano worker organizing, the leaders of New York’s piano manufacturers organized themselves as well into “Pianoforte Manufacturers’ Society of New York.”

The employees and employers eventually settled on a compromise: an immediate 15 percent pay raise, followed by another 10 percent pay raise some time in the future. To recoup the increased labor costs, Steinway simply increased the price of its pianos and found no attendant drop in sales, as it had warned workers. And although business was improving, the manufacturers kept delaying the second 10 percent pay raise it had promised workers.

Before becoming the family-friendly neighborhood it is today, Astoria was home to a host of manufacturing plants. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Even though most piano workers were satisfied with the 15 percent pay raise, workers at two firms, Steinway and Decker Brothers, kept pushing for the second 10 percent pay raise. Soon, workers at other firms were also protesting the postponement, and 1,200 piano workers went on strike, joined by house carpenters, laborers, mechanics, carvers, cabinetmakers, and other woodworkers. In response to this strike, the manufacturers banded together and responded with a lockout, preventing workers at some factories from returning to work to financially support those who were still striking.

Heinrich’s son Henry Jr. had a particularly negative view of the striking workers. He “referred to his 400 workers as ‘swine,’ telling his brothers to fire them all and not to worry because another 400 swine were ready to take their place.” He paid police to contain strikes and jail strikers, and he evicted workers who had rented homes from the firm. His brothers William and Charles, however, were more hesitant to alienate their entire workforce. William wrote in his diary that, at two separate meetings of the manufacturers in 1864, the association resolved “not to give the 10% advance demanded by the workmen.”

But, with the strike continuing to drag on, the manufacturers finally capitulated at the end of March. William wrote, “Charles & I go to piano manufacturers meeting which is very stormy. Resolve at last that each boss be allowed to settle with his own but not to exceed 10 percent and not to take each other’s workmen.” For their own workers, the Steinway brothers finally offered the 10 percent increase, and workers resolved to end the strike at a mass meeting in April.

The strike was a win for the Steinway workers, who received the additional 10 percent that had been previously promised to them. Despite what the manufacturers wrote in their letter in the Times, Steinway increased the prices of its pianos once again to cover the increased labor costs, and Henry Jr. “recognized that the manufacturers had been foolish to renege on the 10 percent increase in the first place.”

1872 Strike for Eight Hours

Although the 1864 strike was resolved, Steinway’s labor troubles were just beginning. The post-Civil War American economy was fundamentally altering the social structure of the country. The 1870s were the beginning of the so-called Gilded Age, a period of gross inequality between the capitalist and working classes during a time of industrialization and urbanization. One of the major ways in which workers responded to the degradation of the Gilded Age was by advocating for an eight-hour work day. In 1870, New York State passed an eight-hour law but made no moves to enforce it.

Workers protested the lack of enforcement and rose up in a series of strikes in the spring and early summer of 1872 in what Werner called “the Great Strike,” which lasted for nearly two months.

Steinway & Sons quickly established itself as superior piano crafters following its move to the United States in 1850. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

During the strike, 500 piano workers met at the Germania Assembly Rooms and voted to strike for an eight-hour work day and a 20 percent wage increase. William Steinway quickly brushed off some of the same talking points his company and other piano manufacturers had used in the 1864 strike, and the New York Times parroted Steinway’s arguments. “The conclusion is irresistible that an eight-hour law, in this trade, would drive a considerable proportion of it out of the City,” the Times wrote.

Privately, though, William believed that the strength of the workers was “so formidable in its character that there is hardly a doubt that they will be successful.” He proposed a compromise of a nine-hour work day or a ten percent wage increase, which many workers accepted but some rejected after some deliberation.

The workers also voted to negotiate directly with the company and to not make this dispute a general trade matter. This direct dealing incensed the unions and led their leaders to present a show of force. “In less than half an hour 3,000 men marched up and surrounded the building, giving three cheers for the trade associations, three more for the eight-hour movement, and three more for the Steinway workmen.” This show of labor force also caught the attention of the local police, who posted officers around the Steinway building because they were “fearing some trouble.”

For workers who didn’t accept Steinway’s compromise, the manufacturers’ association tried to scare them into submission. The association passed a unanimous resolution that pledged “to open our manufactories for ten hours only, and we will in no case accede to less than ten hours’ work by our men.” Steinway & Sons was one of the signatories.

On June 15, 1872, the Steinway strike took an intense turn. Sixty Steinway workers who were still on strike planned to overpower a small contingent of police officers stationed near the Steinway building and seize the factory, resulting in a work stoppage, but a spy employed by William tipped him off to this plan. William, in turn, reported it to the police, who responded with force once the striking workers took control of the building.

The Times wrote in a firm anti-worker tone that “the strikers became so threatening in their language and demeanor that the Police were compelled to interfere.” The Times article also detailed the violent actions of the police officers in a triumphant tone. “The strikers, qualing beneath the shower of blows from the officers’ batons, broke and ran.”

Two days after the police confrontation, the Steinway strike was over. The Times wrote simply that “the piano-makers at Steinway’s have now all resumed.” The Steinway strike for an eight-hour day had been crushed by the company in partnership with the city’s police, with Steinway agreeing only to a ten-percent wage increase. The 1872 Great Strike throughout New York City similarly whimpered to an end.

Escape to Astoria

If the 1864 Steinway strike signaled to the company the need to be wary of labor unions, the 1872 strike convinced it that something drastic must be done to curtail the unions’ ambitions. In response to these labor actions, William Steinway decided to move a portion of the company’s operations across the East River to what is now Astoria.

The move to Astoria was based partly on a belief that the New York City labor movement was teeming with communist influences, which could be avoided by relocating further east outside the city. These communist connections were being made freely during the 1872 strike. The initial vote during which five hundred piano workers struck for the eight-hour work day took place at the Germania Assembly Rooms. “It did not go unnoticed by critics of the strike that the Germania Assembly Rooms had frequently been the scene of Communist meetings,” Werner wrote. This association with communism was significant, as “the employers who were affected got together and blamed Communism for their troubles.”

Steinway & Sons move to its longtime home in Astoria was prompted by a series of labor struggles. Photo by Jim Henderson/Wikimedia Commons

Theodore Steinway’s 1953 history of the company told a sanitized version of the founding of the Steinway village in Astoria. “The story of this community begins in 1870 and 1871, when the firm, partly for expansion, bought a 400-acre tract of farm land in what soon afterward became the northern end of Long Island City … It was here that a model village named Steinway was built by the firm for its employees.” The village had its own post office, public bath, park, library, kindergarten, and volunteer fire department. William Steinway also worked to set up a land company, a streetcar line, a ferry, and a Daimler Motor Company shop to build stationary internal combustion engines and motors in Steinway.

Still, even Theodore admitted that the Steinway village “was the company’s answer – an enlightened one by the standards of the period – to the radical labor agitation that had interfered with their work in the city.”

Lieberman was less charitable in his book, writing that Steinway built the village for two reasons – more worker control and more profits. “One was to try to control his workers, especially during times of discontent. The other was to sell land or rent homes on the 400 acres that Steinway & Sons now owned in western Queens.” In this village, Steinway could exercise even more control over workers than usual through coercive action. William had “power over his workers by enabling him to evict strikers from their houses, foreclose on their mortgages, or restrict their credit at local stores.”

But the move and establishment of the company town did little to quell labor tensions over the long term. “The town grew but never provided William with the control over workers which he had hoped for,” Lieberman wrote. In 1880, starting with a strike of Steinway piano varnishers demanding a pay raise, all workers in both factories in Manhattan and Astoria went on strike, exhibiting cross-river worker solidarity.

In response to this strike, the piano manufacturers association implemented another lockout, shuttering all of their factories. But the workers’ will was stronger than the manufacturers’, and the association eventually ended the lockout and agreed to wage increases. Despite this victory, additional strikes in the years ahead failed, even though they involved workers in both plants.

This strike collapsed after nine weeks. In 1886, Steinway workers took part in yet another failed strike in favor of an eight-hour workday. The Times wrote that “the men felt chagrined at the confessed failure of the eight-hour movement in their trade, and were bitter against the Steinway and Weber men, to the action of whom the failure was charged.”

Ultimately, the legacy of the Gilded Age for Steinway was a move to Astoria, preceded by two major strikes. The first strike in 1864 for better wages succeeded and showed the company the might of the burgeoning labor unions. The second strike in 1872 for an eight-hour workday failed but convinced the company to begin moving its operations to Astoria in an attempt to escape union power.

Today, Steinway workers belong to Local 102 of the International Union of Electronic Workers-Communications Workers of America. Their head of marketing said in February 2020 (just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit) that the company “is still proudly union strong.”

Until the pandemic forced the Astoria facility to temporarily shut down for a few months, piano production had “continued on this site – mostly unabated – though the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, two World Wars, and the Great Depression,” the company wrote in a press release.

In July, Steinway announced “that its historic Astoria factory is fully reopened and once again producing the world’s finest pianos … The company has gradually welcomed back its full complement of more than 200 artisans, along with the managers, foremen, engineers, and other employees supporting Steinway’s manufacturing process.”

The Astoria facility is operational once again, about a century and a half after Steinway first established it as a direct result of the labor struggles fought by the predecessors of those same employees.