Blind vendors keep the courts and government humming

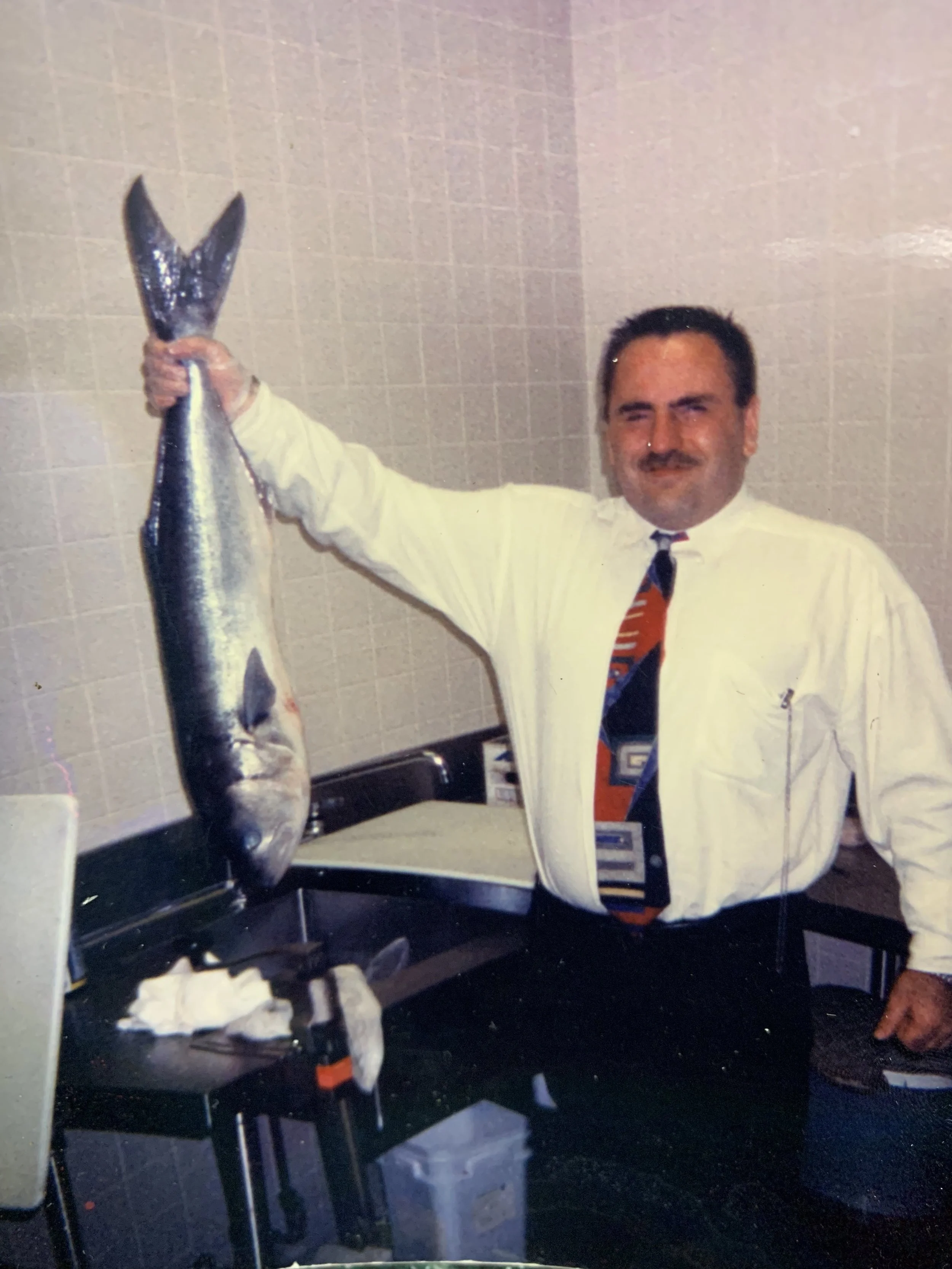

/Angelo Cavallaro holds a fish he caught and brought to his cafe to serve to federal employees. Photo courtesy of Angelo Cavallaro.

By David Brand

Angelo Cavallaro was 21 when a tragic accident stole his eyesight, forcing him to relearn the activities he took for granted just as he was entering adulthood.

Cavallaro also faced another obstacle: the perception that blindness was a disability that disqualified him from most jobs. Though he was strong and eager to work, no employer would hire the Ridgewood resident.

“Twenty years ago, I was desperate for work,” Cavallaro said. ”Being totally blind, I ran into roadblocks — no one would call back.”

Cavallaro, 49, said he fell into a funk after trying in vain to land a job. That’s when he learned about the Blind Enterprise Program, an initiative that trains blind New Yorkers to become vendors and managers at state and federal facilities. The program is overseen by the New York State Commission for the Blind and the Office of Children and Family Services. BEP vendors run food shops and cafeterias at office buildings and courthouses, among other venues.

“I learned I could run my own business and I signed up,” Cavallaro said. “I loved it so much and I excelled because I was grateful to work.”

Nearly two decades later, Cavallaro runs the successful Federal Aviation Administration Cafe in Jamaica. Cavallaro became the founding manager of the FAA Cafe after federal officials recruited him from a venue he managed at the World Trade Center.

Though he runs the show, he remains a hands-on manager, slicing meats, taking out the trash, operating the cash register and modeling hard work for his employees.

There are 75 BEP vendors, including Cavallaro, in New York state. Nationwide, the program employs 2,500 vendors who generate annual revenue of more than $800 million.

The BEP was founded in 1936 to provide work opportunities for blind individuals. Like Cavallaro, numerous vendors have seized a chance too often denied to them by employers wary of blindness.

After completing the program, Cavallaro still faced obstacles at his first job in Manhattan.

“No one would give me a chance,” he said. “They didn’t know how to handle a blind person.”

Until the dishwasher called out.

Cavallaro rolled up his sleeves, dunked his arms in the sink and spent the whole shift scrubbing.

“I tucked in my tie and I washed pots all day,” he said. “I didn’t know it at the time but the manager was watching me, impressed.”

Cavallaro demonstrated that he was capable of the same tasks as his colleagues despite his vision loss. The next week, the deli worker called out and again it was Cavallaro’s time to shine.

“I stepped up to the plate,” he said. “I grabbed a knife and cut 500 rolls and meats.”

The rest is history.

Today, Cavallaro lives with his wife and children in the home he owns in Long Island. He credits his success to the opportunity he got through the BEP.

“I have a flourishing business,” he said. “I just needed that opportunity.”