Opinion: Remembering John Swett Rock, a pioneering Black attorney

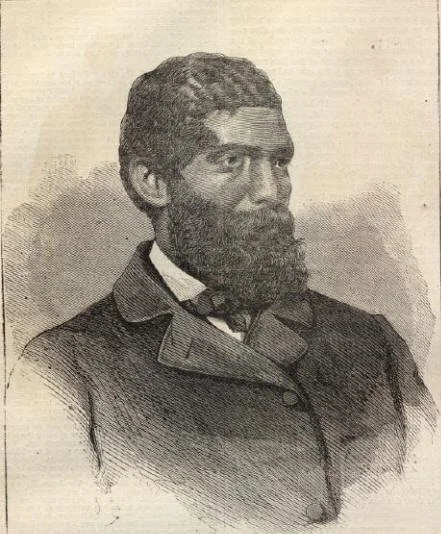

/John Swett Rock was the first Black person to be admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

By Hon. Maurice E. Muir

John Swett Rock was a teacher, dentist, medical doctor and abolitionist, in addition to being Massachusetts’ fourth Black lawyer, and the first Black person admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court.

Rock was born on October 13, 1825, in Salem, New Jersey to free parents. After acquiring an education in Salem public schools, he became a schoolteacher and taught in a one-room schoolhouse in New Jersey from 1844 to 1848. Rock also taught evening classes at a local high school where he was responsible for beginning a night school for Black students.

Deciding to take up the practice of medicine, Rock studied under two white physicians, Drs. Sharp and Gibbons. Upon completing his apprenticeship, he applied to medical schools in Philadelphia, but was denied admission because of his race. Consequently, he apprenticed under a white dentist and opened a dental office in Philadelphia in 1850. Thereafter, he was admitted to the American Medical College and received his Doctor of Medicine Degree (“M.D.”) in 1852. The following year, he opened an office of dentistry and medicine in Boston and was the second black admitted into the Massachusetts Medical Society. Dr. Rock practiced medicine for several years until 1860, the year preceding the beginning of the American Civil War.

While there is little information surrounding his decision to become a lawyer, it has been established that he was a vociferous opponent to the institution of slavery. Given the dramatic transition from dentistry to law, it can only be surmised that he became a lawyer based on the precept that he could more effectively combat slavery as a lawyer than as a physician. For several years, Rock traveled across the country fighting for the abolition of slavery, protesting the colonization movement, advocating Black capitalism and emphasizing the responsibilities of educated and well-to-do Blacks to use their resources to benefit the Black community. He gave many speeches, some of which were delivered before the Massachusetts Legislature. One speech of major import was made at Faneuil Hall about Crispus Attucks in commemoration of the Boston Massacre and in protest of the United States Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision where Chief Justice Roger B. Taney declared that all Blacks – slaves as well as free – were not and could never become citizens of the United States.

A throat condition ended Rock’s public speaking activities. Despite a federal order that ruled that Black people were not citizens and therefore could not obtain passports to travel abroad, the Massachusetts legislature granted Rock a state passport that allowed him to travel to France for a throat operation. Rock was operated on by Dr. Auguste Nelaton, a member of the French Academy, who advised him to curtail his speaking engagement and his medical practice. Nonetheless, upon returning to America, Rock was commissioned by the Vigilance Committee to provide medical services to ailing fugitive slaves and worked for the creation of a Black militia. He also addressed a committee of the Massachusetts House of Representative asking that the word “white” be deleted from the militia laws, and during the Civil War, he served as a Recruiter for the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Regiment of black volunteers. However, Rock did comply with his doctor’s order to give up his medical practice, embarking upon a legal career instead. It is unclear with whom he studied law, but on Sept. 14, 1861, upon a motion by Attorney T.K. Lothrop, he was admitted to practice in all of the courts of Massachusetts and almost immediately thereafter was appointed Justice of the Peace in Boston. He also opened a law office on Tremont Street, in Boston.

When U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Taney died in 1864, he was succeeded by Salmon P. Chase, who was an abolitionist attorney from Ohio. Justice Chase’s appointment occasioned Dr. Rock to write Charles Sumner, then U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, of his hopes for the future, stating, “. . . I think my color will not be a bar to my admission [to the U.S. Supreme Court]” and indeed it was not.

On February 1, 1865, the same day that Congress approved the 13th Amendment outlawing slavery, Rock became the first Black person to be admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court. Sponsored by Senator Sumner, Rock’s admission was granted without question. The New York Tribune dramatically described the event:

“The black man was admitted. Jet black with hair of an extra twist – let me have the pleasure of saying, by purpose and premeditation, of an aggravating ‘kink’ – unqualifiedly, obtrusively, defiantly ‘N–r’ – with no palliation of complexion, no let-down lip, no compromise nose, no abatement whatever in any facial, cranial, osteological particular from the despised standard of humanity brutally set up in our politics and in our Judicatory by the Dred Scott decision – this inky hued African stood, in the monarchical power of recognized American Manhood and American Citizenship, within the bar of the Court, which had solemnly pronounced that black men had no rights which white men were bound to respect; stood there a recognized member of it, professionally the brother of the distinguished counsellors on its long rolls, in rights their equal, in the standing which rank gives their peer. By Jupiter, the sight was grand.”

Rock’s admission to practice before the Supreme Court of the United States had a tremendous impact on the judiciary. Historian J. Clay Smith explained, “Rock’s admission would make it exceedingly difficult for any inferior court to exclude black lawyers from admission solely on account of race; as Charles Sumner wrote, ‘[i]t helped the way for admission of his race to the rights of citizenship and especially the right to vote.’”

Ironically, while Rock was returning to Boston, after being sworn-in before the United States Supreme Court, he was arrested for not having his “pass” – the Certificate of Freedom, Black people were required to carry – in his possession. This incident led then Congressman James A. Garfield, who later became the 20th President of the United States, to introduce a bill that abolished the law requiring Black people to carry a Certificate of Freedom.

Nevertheless, Rock later became the first Black person to address the U.S. House of Representative. His Biographer, John SW. Forbes, later wrote “. . . it seemed remarkable that a colored man should know enough law to practice before the Supreme Court. The rank and file of the members simply regarded the visitor as a prodigy in law.”

On Dec. 3, 1866, approximately one year after being admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court, Rock died of tuberculosis. Even though Rock had little financial success, he left an indelible mark on society. He was buried with full masonic honors, from the Twelfth Baptist Church. His tombstone at Woodlawn Cemetery recorded his accomplishment as the first Black person to be admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court.

Hon. Maurice E. Muir is a Queens Supreme Court Justice