Queens advocates see legal weed through racial justice lens

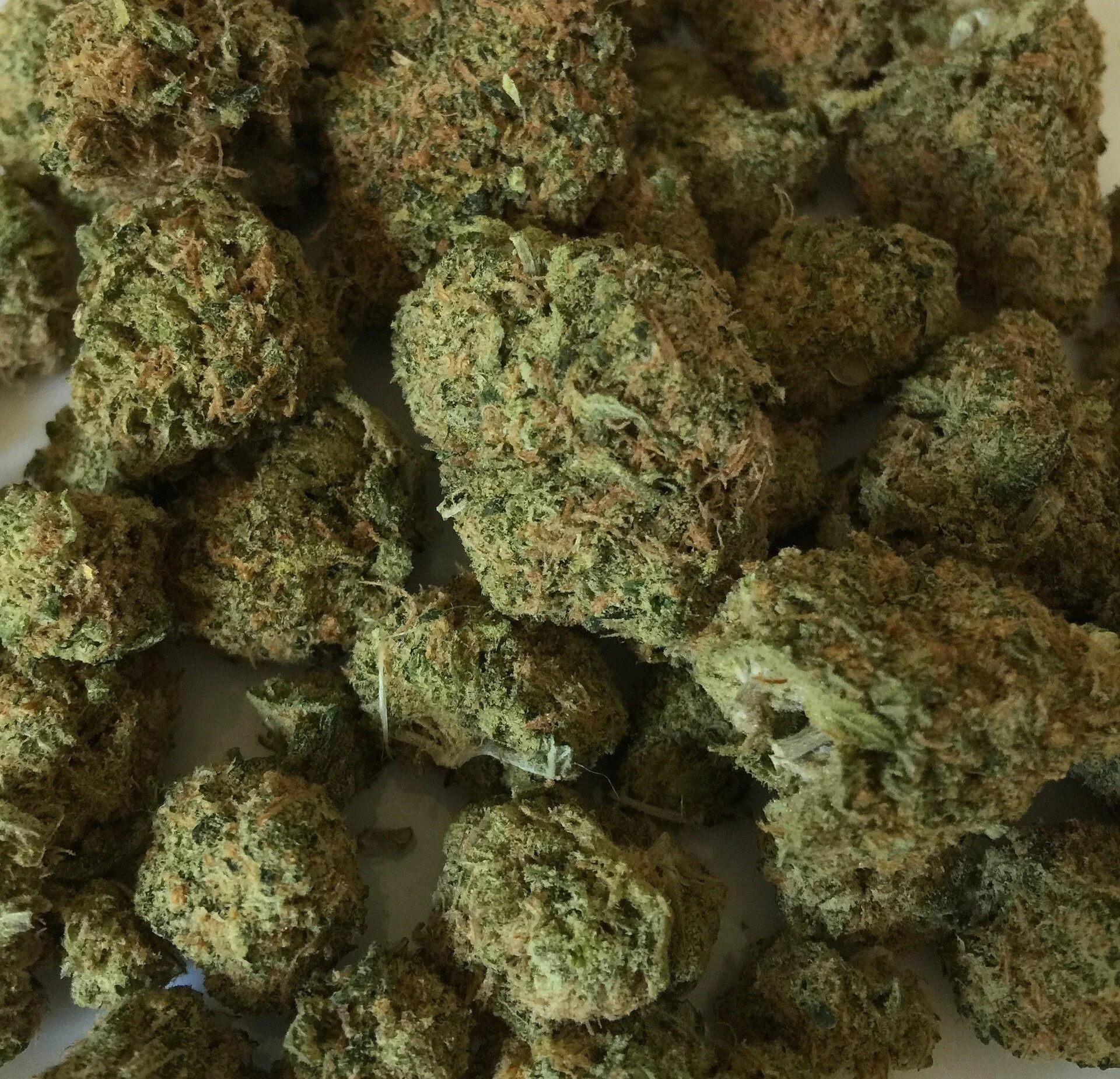

/Dozens of activists gathered Tuesday to call for equitable Marijuana legalization. Photo via pixabay

By Rachel Vick

The few legal marijuana dispensaries in Queens are each located in predominantly white and relatively wealthy communities. They are owned by large corporations led by white executives.

Nationwide, few shops are owned by African Americans and Latinos most affected by the War on Drugs that filled jails and prisons with people of color charged with petty drug crimes.

As state lawmakers prepare to make weed legal statewide, advocates in Queens say those are the very communities that should benefit from the new revenue stream.

“We need to focus on clearing the pathways for those who have suffered the deepest,” Citizen Action New York Political Director Stanley Fritz told the Eagle Tuesday. “We’re facing a challenge now where New York could [legalize] in a way where the state could block poor Black and brown people from entering the industry — businesses in Black communities run by white people will dominate the industry if we do that.”

Black and Latino New Yorkers account for nearly every person arrested for marijuana in the city, even with weed decriminalized and several district attorneys declining to prosecute low-level possession. Last year, 93 percent of people arrested for marijuana-related offenses were Black or Latino, according to NYPD data.

The three marijuana dispensaries in Queens are located in Forest Hills, Briarwood and on the border of Elmhurst and Rego Park. There are also a handful of doctors able to issue medical cards in neighborhoods across the borough.

Fritz said the state must pass a law that gives Black and Latino New Yorkers priorities for licensing new dispensaries once marijuana becomes legal. The facilities should also hire Black and Latino New Yorkers and people who have been jailed for drug crimes.

He said he favors the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act introduced every session since 2013 by Manhattan State Sen. Liz Krueger. The bill would give opportunities to Black and Latino entrepreneurs from the communities disproportionately impacted by the War on Drugs, while investing tax revenue into the state’s education fund and social programs, like the Community Reinvestment Grant.

He said marijuana legalization should mean opportunities for people in South Jamaica, not just Astoria and Long Island City.

“The MRTA is the way to do it,” he added. “That’s the bill with the equity we need to help our community, but we have to be mindful of, in the final stages, what concessions are being asked of us and what changes are being proposed.”

At a rally Tuesday, advocates and lawmakers from across New York called on the state to pass laws that promote equity in any new legal marketplace. Speakers, like Queens Assemblymember Khaleel Anderson, backed the MRTA as the clearest path to equity.

“We’re going to make sure we reinvest revenue into communities, the ones most harmed by the failed War on Drugs,” Anderson said. “We can’t arrest or criminalize our way out of social ills that are impacting our communities.”

Communities most impacted by the war on drugs need to remain at the center of legalization, advocated said Tuesday. Screenshot via Zoom

Anderson said courts must expunge past marijuana-related convictions — an effort that he said would take consistent advocacy.

Activists at the rally criticized Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s goal of using the “Cannabis Regulation and Taxation” to fill the holes in the budget rather than invest in communities impacted by drug arrests.

The Cuomo-backed bill differs from the MRTA because it has more restrictions on possession, criminalizes home grown plants and allows New Yorkers to keep a fraction of the amount of weed allowed in New Jersey, which legalized marijuana in a referendum last year

New Jersey’s marijuana laws will direct 30 percent of sales tax revenue to maintaining regulation infrastructure, with the rest used to fund social justice programs. The New Jersey laws also establish “impact zones” that give the hardest hit communities priority licensing.

“If we can’t do better than New Jersey then what the heck are we talking about here?” said Anne Oredeko, a supervising attorney in Legal Aid’s Racial Justice Unit.

Under the CRTA, “there will be two New Yorks,” Oredeko said.

Officials from the Cuomo administration pointed to amendments to the legislation, including the allocation of $100 million to a Cannabis Social Equity Fund, which would be distributed through local governments and community-based organizations. Once fully implemented, legal marijuana is expected to create $300 million in tax revenue statewide.

“The governor and the legislature are entirely aligned in guaranteeing that the new cannabis law is firmly rooted in equity principles,” a spokesperson for the governor said. “From licensing opportunities to re-investment, there is no daylight between the executive and the legislature. The current negotiated bill will be the most progressive in the nation on that front.”

But opponents of that plan say the CRTA does not go far enough to advance racial justice.

Marijuana prohibition has always punished people of color, said Bronx native Yusuf Abdul-Qadir of the Syracuse Police and Accountability Coalition. The first laws criminalizing marijuana were fueled by a stereotype that the drug was primarily used by Black and Latino Americans, particularly people of Mexican descent.

“Legalization is essential and it is essential to take legalization from a racial justice perspective,” Abdul-Qadir said.