As NYC homeless sweeps surge, advocates say strategy fails to keep people off streets

/Lukasz Ruszczyk has spent the past several months living near the train tracks that divide Ridgewood and Glendale. Eagle photo by David Brand

By David Brand

It’s become a weekly event for Lukasz Ruszczyk: Sanitation workers visit him on the sidewalk beneath the train tracks that mark the Ridgewood-Glendale border. A Department of Homeless Services employee encourages Ruszczyk to move into a city homeless shelter and looks on as the Sanitation crew tosses his stuff into a garbage truck.

Ruszczyk declines the recommendation to leave, and the laborers come back a few days later. They have visited three times in March, according to notices left by outreach workers informing Ruszczyk of the pending sweeps.

Ruszczyk, 38, says they can keep coming. He has no intention of leaving unless it means securing a permanent and private home.

“I went to a shelter. I was robbed several times,” he told the Eagle Tuesday, minutes after the latest sweep. “I’d rather freeze than go back.”

Over the past fifteen months, city officials have stepped up sweeps, or “clean ups,” of homeless encampments across the five boroughs.

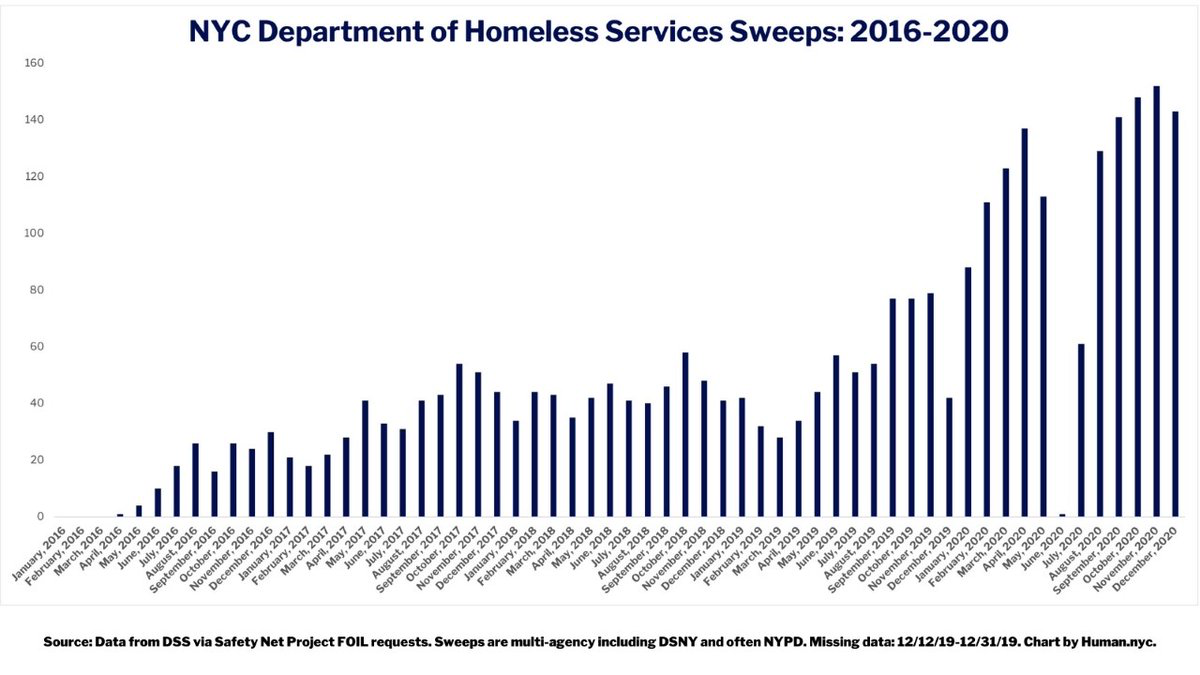

DHS coordinated with city agencies to conduct 1,347 such sweeps last year, more than double the 616 completed between Jan. 1 and Dec. 11, 2019, according to DHS records. The agency provided the data to the Urban Justice Center’s Safety Net Project in response to a Freedom of Information Law earlier this year. The New York Times reported on a portion of the data earlier this month.

About 54 percent of last year’s sweeps, 726 of 1,347, occurred in Manhattan. There were 195 sweeps in Queens, or about 14 percent of the total. In Brooklyn, there were 293; the Bronx, 125; and Staten Island, eight.

Homeless sweeps have surged over the past two years, according to data from DHS charted by human.nyc. Image courtesy of Josh Dean

The sweep surge contradicts guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which recommends that municipalities allow people to remain in encampments unless they are guaranteed private rooms. In New York City, they are not.

Advocates for street homeless New Yorkers say that, in addition to violating public health guidance, the sweep strategy simply does not work to keep people off the streets.

“They just move people around,” said Josh Dean, executive director of the advocacy organization Human.nyc. “We’re calling for an end to sweeps, not just because they’re cruel, which they are, but they’re really counterproductive.”

If the sweeps were effective, Dean said, city workers wouldn’t have to return to the same Queens overpass to throw out Ruszczyk’s refuse and belongings three times in less than three weeks. The punitive action only erodes trust in outreach workers and further discourages street homeless New Yorkers from agreeing to city services, he said.

Human.nyc released a four-point proposal Tuesday to end street homelessenss and move New Yorkers into safe and secure permanent housing. One of the pillars calls on the city to “reimagine” outreach by hiring formerly homeless peer workers and allowing teams to provide items like socks and warm meals to people staying in public spaces. Current policy prohibits that direct assistance under the premise that it encourages people to remain outdoors.

The proposal, called the Human Plan, says that’s a misguided notion. Small assistance allows outreach workers to build bonds and trust with homeless New Yorkers, Human.nyc said.

“If they cannot help in the immediate term, homeless New Yorkers tell us, they have no reason to believe they can help in the long-term,” the plan states.

The Human Plan also urges the city to increase the number of temporary “stabilization beds” for people coming off the street and to rapidly move street homeless New Yorkers into permanent housing — the key way to actually end homelessness. To accomplish that goal, the city must develop more supportive housing units and remove barriers to apartments that already exist, according to the proposal.

DHS says its current model works, however.

The agency did increase the number of stabilization beds last year. And the city moved thousands of homeless single adults out of congregate shelters, where residents sleep in shared spaces, and into hotel rooms with just one or two beds each to allow for social distancing.

The city has added 1,300 beds for street homeless New Yorkers since January 2020, coinciding with the surge in sweeps, said DHS spokesperson Ian Martin. Since establishing its current outreach model, known as HOME-STAT, in 2016, the city has helped more than 4,000 people move off the streets and into shelters.

DHS contracts with the organization Breaking Ground to conduct outreach with each street homeless New Yorker an average of three times a day. Breaking Ground is now working with 33 individuals staying outdoors in Queens and building relationships with 10 others, they said.

Still, the city has an obligation to address “obstructions of public places or encampments” even if agencies cannot compel people to move into a shelter, Martin said.

When Sanitation, the Department of Transportation or another agency “addresses a condition on the streets, we at DHS and our outreach partners are on hand, continuing to engage any individuals on-site, building on trust and relationships with those individuals, and outlining the range of services available to them, in order to encourage them to accept services and transition off the streets,” Martin added.

Despite those efforts, thousands of New Yorkers continue to sleep in public spaces.

Volunteers participating in an annual point-in-time count of street homeless New Yorkers identified 3,857 people on subways or public spaces on Jan. 27, 2020, the most recent tally.

Ruszczyk said he has no intention of leaving the sidewalk if there is a chance he will be placed in a large group setting, like the intake shelter for adult men at 30th Street in Manhattan.

He said he became homeless after he was ejected from a Ridgewood apartment building owned by his family last year. He said he threatened tenants who had failed to pay rent and they filed an order of protection against him, forcing him to leave.

He moved into a shelter and continued working in construction until the pandemic hit, he said. There, he said, other residents stole his phone and left him unable to find out about jobs. It was one of several thefts that compelled him to leave, he said.

“I said, ‘My stuff is missing. I lost my job.’ It left me with no money, so I left,” he said.

He came back to Ridgewood and began sleeping on church steps and sidewalks. At one point, he said, Sanitation workers threw out his construction clothes, making it even harder to find work.

Video of the encounter Tuesday shows a Sanitation crew chief asking Ruszczyk what he could discard and suggesting that Ruszczyk hold onto a toothbrush. Activists from who filmed the sweep contacted the Eagle, which arrived as the garbage truck was leaving.

Other encounters are harsher. Activists have filmed workers throwing away walkers and homeless New Yorkers have repeatedly reported laborers discarding their identifying documents.

Raquel Namuche, an organizer with the group Ridgewood Tenants Union, has been working with Ruszczyk and visited him following the sweep Tuesday. RTU has provided food, toiletries and support to Ruszczyk and other New Yorkers experiencing homelessness in and around the neighborhood.

Namuche has urged the city to provide safe, private and appropriate spaces for people staying outside.

“A lot of these folks want to be indoors, but they’re traumatized by their experiences in shelters,” she said. “We want to know what they’ll do to get people housed.”

Dean, of Human.nyc, said officials and the public tend to blame street homeless New Yorkers rather than consider the resistance to shelters a logical response to services they consider dangerous, unhealthy or fruitless.

“They do that to shift the blame from their own systemic shortcomings to homeless New Yorkers,” Dean said. “It’s not that people on the streets are service resistant; it’s not that they don’t want to come inside. It’s that they don’t have the right offer.”