Queens pol’s ‘lobbying loophole’ bill passed by Senate

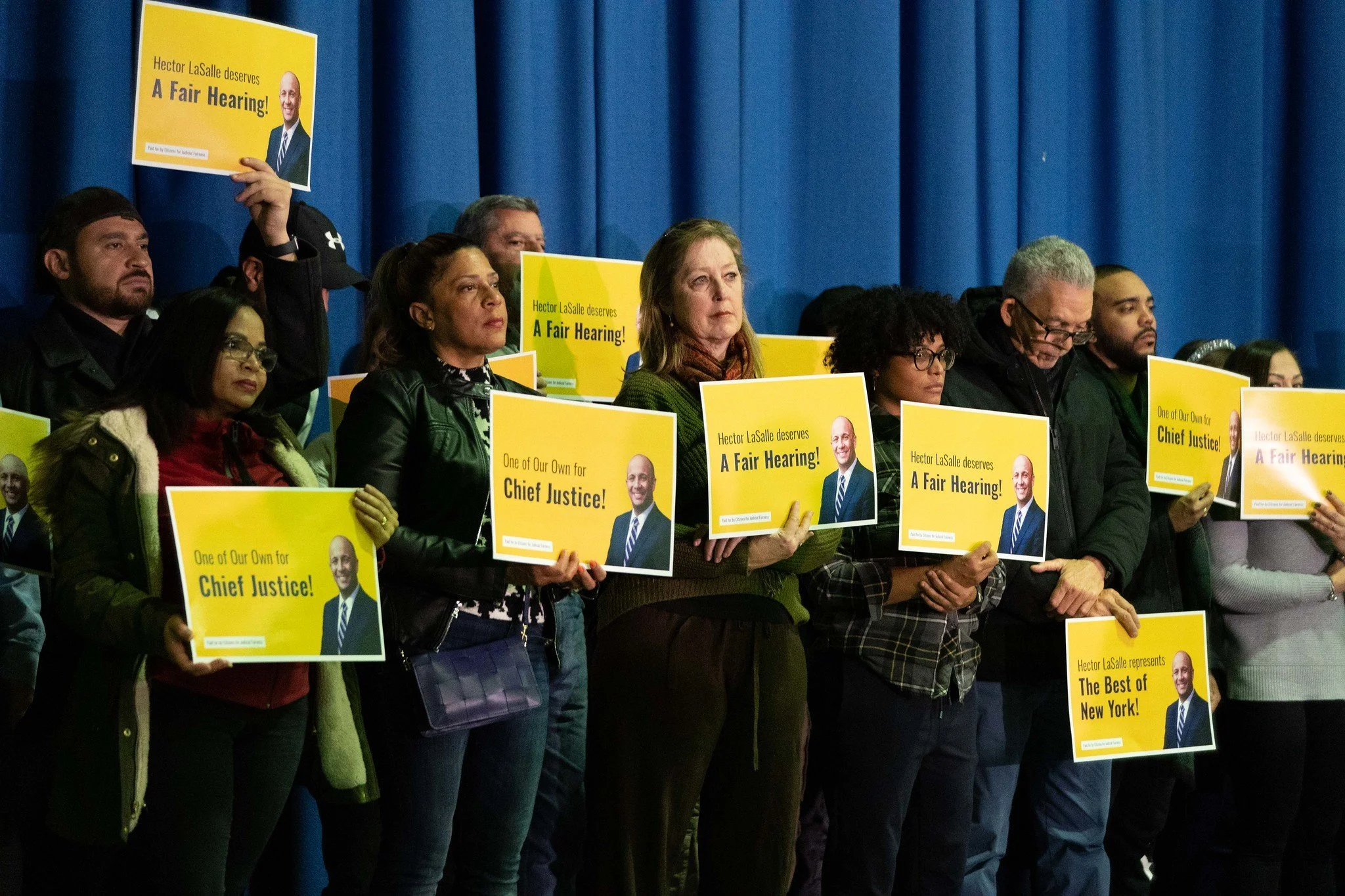

/The chief judge nomination of Hector LaSalle last year saw an unprecedented amount of lobbying from groups both in support of and against the nominee. None of the lobbying was required to be publicly reported under current state law. A bill from Queens State Senator Michael Gianaris is attempting to change that. File photo by Don Pollard/Office of Governor Kathy Hochul

By Jacob Kaye

The State Senate this week passed a bill created in response to lobbying efforts in support of and against Governor Kathy Hochul’s controversial pick for chief judge last year.

The bill, sponsored by Queens State Senator Michael Gianaris, would close what the lawmaker dubbed a “lobbying loophole” surrounding judicial nominees, which was exposed for the first time following the governor’s chief judge nomination of Hector LaSalle in the final days of 2022.

The bill, which was also passed by the legislature in the previous legislative session but vetoed by the governor just before the start of 2024, would require detailed and public reports on lobbying done for any state office nominations, including judicial nominations. The legislation, which enjoyed bipartisan support during its first advancement through the legislature last year, was passed with a 44 to 17 vote this week.

But before the bill’s passage, a debate on the floor of the Senate rehashed old tensions that came to a head in early 2023 and nearly resulted in a constitutional crisis.

“This is a political bill that is cloaked in transparency,” said Senator Anthony Palumbo, who sued the State Senate over its handling of the LaSalle nomination last year.

But Gianaris, who opposed LaSalle’s nomination, defended the bill, claiming that the measure would make lobbying on nominations as transparent as any other lobbying efforts made in Albany. He also said that the timing of the bill had less to do with his opposition to LaSalle’s nomination than it did with the unprecedented lobbying efforts made for and against the nominee.

“It's a simple idea,” Gianris said.

“If Senator Palumbo wants to vote, ‘No,’ and tell the people of New York he'd rather lobbying on nominations be conducted in secret, that is certainly his right as a member of this body,” he added. “But I, for one, will be voting, ‘Yes.’”

LaSalle’s nomination was unique, and generated more public interest than potentially any other chief judge nomination before it.

Spending on lobbying for a chief judge nomination was virtually unprecedented, and began to raise concerns from lawmakers and good government groups primarily because there was no legal requirement to disclose who was funding the efforts.

A bulk of the lobbying around LaSalle’s nomination came from three groups, two of which were pushing for lawmakers to cast a vote in favor of making LaSalle the chief judge of the Court of Appeals.

The Court New York Deserves, a coalition of criminal justice and progressive groups, quickly expressed their opposition to LaSalle’s nomination, which they began to voice prior to his selection by the governor. Their lobbying primarily took the form of writing opinion pieces and placing them in news outlets. They also met with a number of Democratic senators, which Palumbo mentioned from the floor of the Senate on Tuesday.

The Court New York Deserves were soon joined by a number of state senators, including Gianaris, who said that they would vote against LaSalle when he came before them.

In response, two groups, Latinos for LaSalle and Citizens for Judicial Fairness, began spending on lobbying efforts to express their support for the nominee.

Latinos for LaSalle featured a number of prominent former elected officials of Latino descent and counted Luis Miranda, a political consultant and father to Broadway star Lin Manuel Miranda, and Roberto Rodriguez, a longtime lobbyist, as supporters.

Citizens for Judicial Fairness, an opaque lobbying group that, until last year, was focused exclusively on reforming Delaware's top business dispute court, began purchasing online ads that urged New Yorkers to call their senators and express their support for the nominee.

But who was behind the group wasn’t immediately clear – unlike Latinos for LaSalle and The Court New York Deserves, Citizens for Judicial Fairness did not publicly advertise its members or supporters.

The Eagle was the first to report the connection between Citizens for Judicial Fairness, which was previously called Citizens for a Pro-Business Delaware, and Tusk Strategies, a powerful New York-based lobbying firm.

The group was formed around eight years ago by the lobbying firm and the founder of New York-based translation company TransPerfect after Deleware’s Chancery Court forced a sale of the company. Around 5,000 employees of the company came on as the group’s earliest members.

Tusk Strategies lists both Citizens for Pro-Business Delaware and Citizens for Judicial Fairness under a section of its website titled “Wins,” and Citizens for Judicial Fairness is run by Chris Coffey, the CEO of Tusk Strategies.

A bill from State Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal to reform the Commission on Judicial Conduct – that was partially prompted by the abrupt resignation of former Chief Judge Janet DiFiore – is supported by a number of good government groups. File photo via NY State Senate

The group reportedly spent between $75,000 and $100,000 on the campaign, none of which was reported to the state – and it didn't need to be.

Should the bill be passed by the Assembly, it will head to the governor later this year.

Hochul vetoed the legislation just before the New Year because it would have allowed for the state to go back and require retroactive lobbying reporting. As such, the measure would have required those who lobbied for or against LaSalle to report their work.

“This bill would broadly expand the definition of reportable lobbying to include the nomination of a person to state office or their confirmation by the State Senate,” Hochul said in her veto of the bill issued in December. “This bill would impose significant new reporting requirements on people who might not already be reporters, retroactive January 1, 2023.”

“Additionally, this would impose implementation costs not already accounted for in the state financial plan,” she added. “Therefore, I am constrained to veto this bill.”

But the version of the bill passed by the State Senate this week has one major change – it no longer includes the retroactive reporting requirement.

Despite the change, Palumbo rehashed the lobbying work done by the Court New York Deserves and accused Gianaris of attempting to pass a bill that would force his political foes to publicly identify themselves. But with the retroactive reporting requirement nixed, Gianaris said his Republican colleague’s argument was moot.

“The activity on previous nominations has…nothing to do with his bill, which is simply prospective,” Gianaris said. “We could talk about those two nominations, we can go back in time and talk about nominations 20 years ago, but they would all have the same relevance to this proposal.”

Palumbo has been fighting with Democratic leadership in the Senate over LaSalle’s nomination for around a year.

The Republican lawmaker brought a lawsuit against the Senate shortly after its Judiciary Committee, led by Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal, voted to reject LaSalle and end his nomination process on Jan. 18.

Like the governor, who was not party to the suit but floated the idea of taking legal action against the legislature, Palumbo argued that the state’s constitution required any judicial nominee coming before the Senate to get a vote by the full Senate, not just a committee.

In mid-February, Senate Democrats again called for a vote on LaSalle’s nomination. This time, the Judiciary Committee advanced the nominee to the full Senate without a recommendation and then, as a full body, rejected the nomination.

LaSalle was the first chief judge nominee in history to be rejected by the Senate.