‘I cried that whole night’: Families say DOC did little to tell them their loved ones died on Rikers

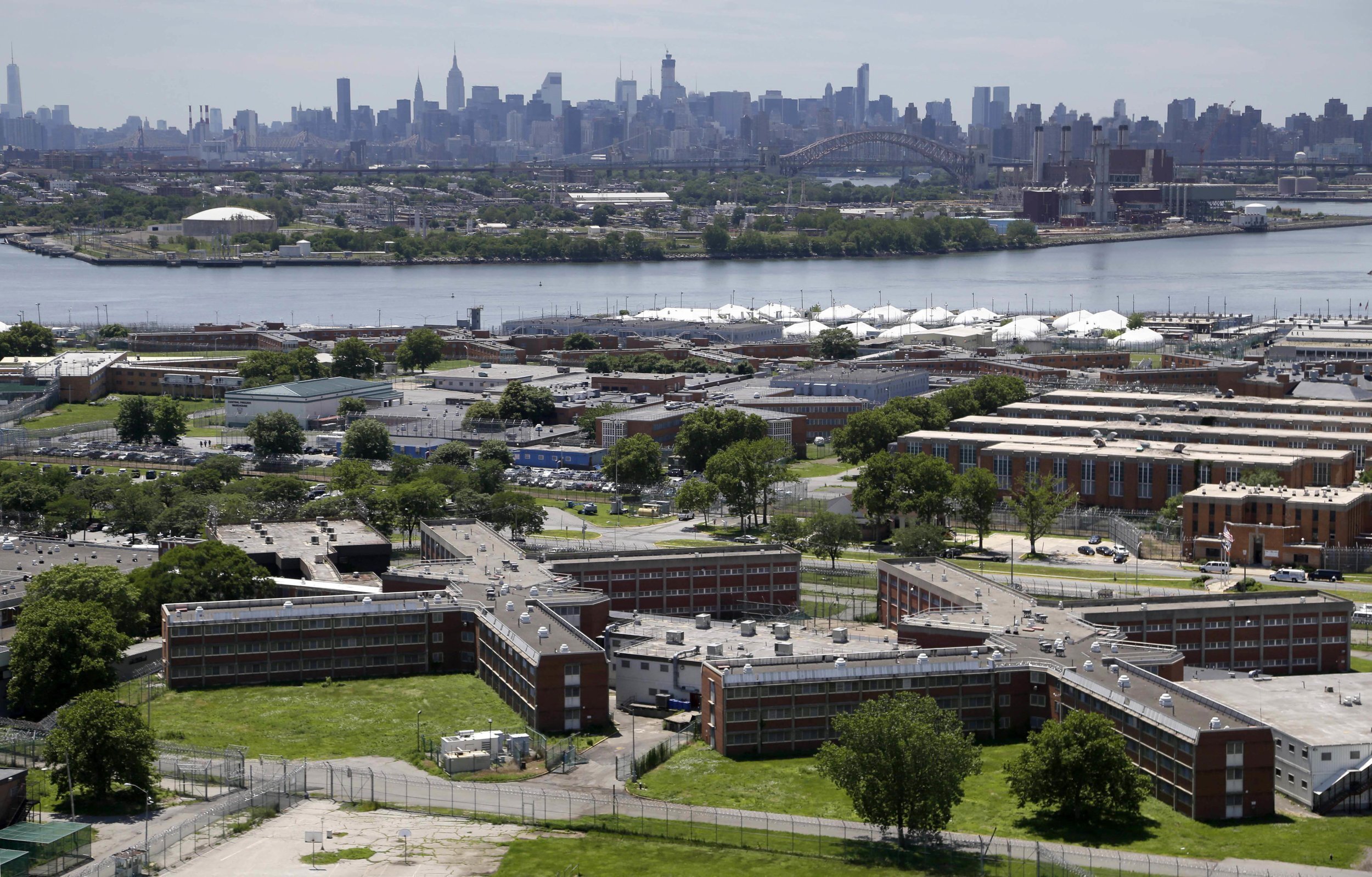

/The City Council on Friday held a hearing on a number of bills regarding transparency on Rikers Island, including one that would force the Department of Correction to notify a person’s next of kin if they die while incarcerated. AP file photo by Seth Wenig

By Jacob Kaye

Lezandre Khadu didn’t know that her son had suffered three seizures while being held in the city’s jails in 2021, the third year of his incarceration as he awaited trial.

It wasn’t until someone incarcerated alongside her son, Stephan Khadu, called Khadu’s daughter and told her that Stephan was going to the hospital that she learned that anything was wrong at all.

Khadu and her daughter rushed to Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx but were told by a Department of Correction officer that they couldn’t see the then 22-year-old. The officer revealed only one detail.

“‘I’ll tell you one thing, he’s not dead,’” Khadu recounted the guard telling her during a City Council hearing on Friday. “I left, and I cried that whole night.”

The incident was an unfortunate sign of things to come. Not long after, Khadu’s daughter would receive a similar phone call. This time the family would learn that Stephan Khadu had died.

Khadu appeared before the council’s Criminal Justice Committee on Friday as lawmakers considered a suite of bills they say will bring more transparency to the city’s troubled Department of Correction.

Among the pieces of legislation was one backed by the committee’s former chair, Carlina Rivera, that would define protocols for the DOC to follow when notifying the family of a person in custody who either died or suffered a medical emergency that led to their release from DOC custody, a practice known as compassionate release.

The bill also defines how the DOC should notify the public and the Board of Correction, the civilian watchdog group that has oversight over the BOC.

A separate bill discussed Friday would define the procedures the DOC and Correctional Health Services – the branch of the city’s hospital system that provides medical care on Rikers Island – should take to notify an incarcerated person’s emergency contacts when that person is seriously injured, hospitalized or attempts suicide. The bill is backed by Councilmember Lincoln Restler.

Khadu wasn’t the only New Yorker to tell the City Council on Friday that the DOC did little to notify her of her loved one’s death. Several family members of New Yorkers who died in DOC custody testified during the hearing.

The council hearing comes around a year after the DOC suddenly stopped notifying the media of deaths in custody.

City Councilmember Sandy Nurse led a hearing on a number of bills aimed at making the Department of Correction more transparent on Friday, Sept. 27, 2024. AP photo by John McCarten/NYC Council Media Unit

The change, which came under former DOC Commissioner Louis Molina, sparked outrage among advocates, attorneys and lawmakers who said that the policy change was just another example of how the DOC made itself purposefully opaque. The change in policy also came at a time when deaths on Rikers Island were particularly high. In 2021, 16 people died in the city’s jails, 19 people died in 2022 and nine people died in 2023.

The DOC resumed notifying the media of in custody deaths under Commissioner Lynelle Maginley-Liddie, who was appointed in December, but those testifying on Friday said transparency issues have persisted.

Khadira Savage, the sister of Roy Savage, a 51-year-old who died of cancer while being held in Bellevue Hospital’s jail ward in March, said that as the detainee’s next of kin, she wasn’t notified about his deteriorating condition.

In November 2023, Savage was moved from a New York State prison to Rikers Island after a panel of appeals judges overturned his murder conviction. As he awaited retrial in the city’s jails, his cancer worsened and he was moved to the jail ward in the city hospital.

For around two months, Khadira Savage attempted to visit her hospital, but was turned away by correctional officers.

It wasn’t until the day before his death that she was allowed to see Savage, who had shrunk down to 100 pounds, Khadira Savage testified on Friday.

“I was so confused as to why there was no communication about my brother's health declining so rapidly,” she said. “The least they could have done was contact me to notify me that my brother's condition had worsened.”

“It was like once he was placed in DOC custody, all communication was cut,” she added. “By the time anyone saw my brother again, he was unable to speak, eat or move to explain what had happened.”

The DOC defended its efforts to notify family members of incarcerated individuals who either die in custody or experience serious medical issues. According to First Deputy Commissioner Francis Torres, immediately after a person in custody dies, the agency deploys a chaplain to notify the person’s next of kin.

“We believe it is imperative to make these notifications in person and to make them first to the next of kin, so that they do not have to hear about the loss of their loved one from a press release or otherwise in the absence of support,” Torres said.

Agency officials said Friday that they were opposed to both bills.

City Councilmember Sandy Nurse, who chairs the committee, said that the bills were necessary to codify the actions of a department that “remains in turmoil with the looming threat of a federal takeover because of its failure to remedy the unconstitutional conditions of confinement on Rikers Island.”

“As long as the level of danger posed to people in custody and employees remains unacceptable, the council has an obligation to use its legislative authority to create a safer jail system,” she said. “Failure to take urgent and necessary action will only result in more tragedy and heartache.”