Welcome to Queens: Migrants share their experiences at Creedmoor shelter

/A number of migrants being housed at the city’s shelter at the Creedmoor Psychiatric Centber board a Q43 bus. Nearly 1,000 migrant men are currently housed at Creedmoor in Queens Village.Eagle photo by Ryan Schwach

By Ryan Schwach

On Hillside Avenue in Queens Village, 40-year-old Fallou Ndoye waits for the Q43 bus to take him to a cleaning job somewhere else in Queens. The work is spotty – he’s called when he’s needed.

“Getting [work] is not guaranteed every day,” Ndoye, a migrant from Senegal, told the Eagle through an iPhone translation app. “It's complicated for us, the conditions here.”

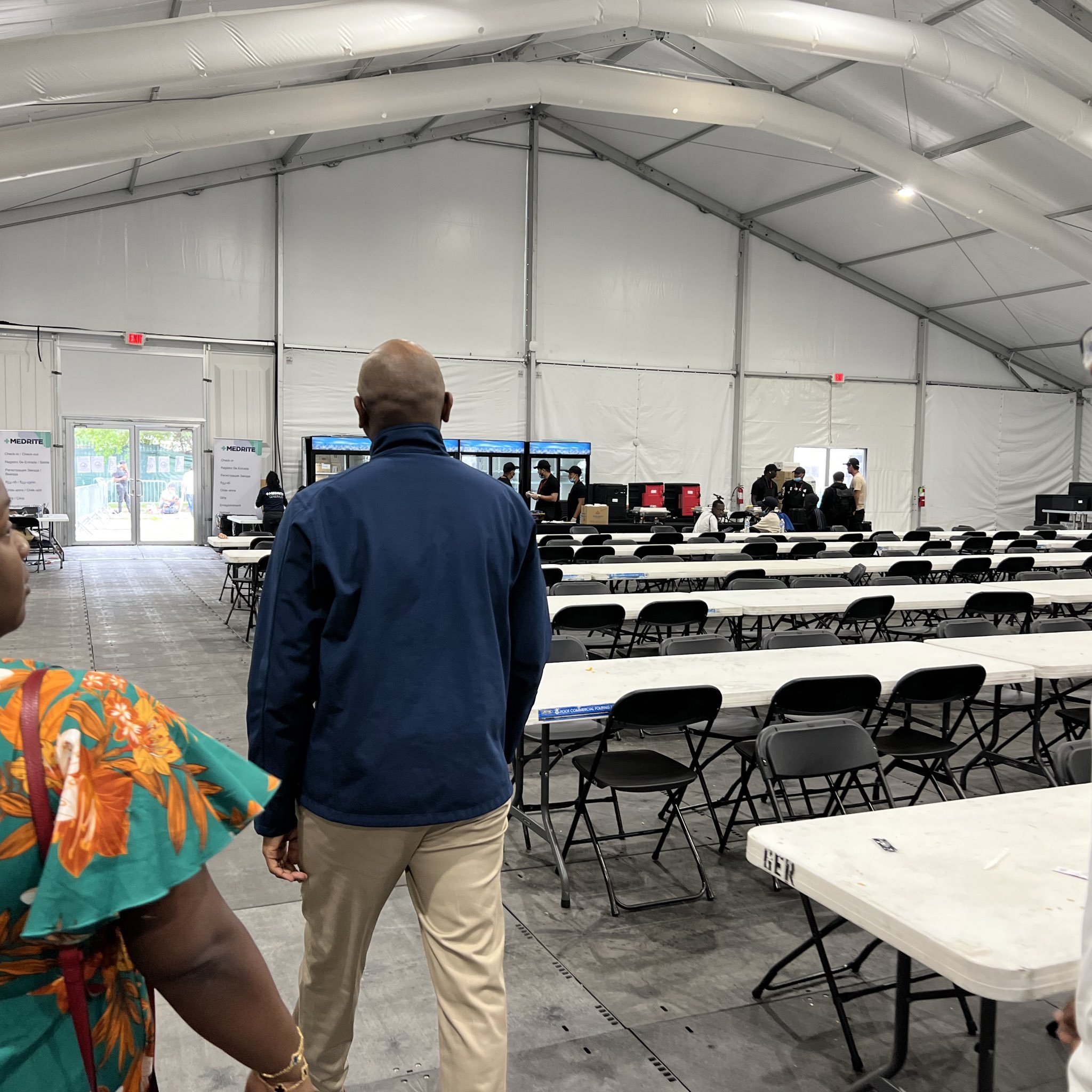

Ndoye is one of nearly 1,000 men who are now temporarily housed at the recently-opened Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Center located on the sprawling campus of the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, a city-run shelter that has been meet with anger from a number of electeds and local leaders on both sides of the aisle.

At the shelter just steps away from Hillside Avenue in one of the furthest corners of Queens, the crisis that has seen over 100,000 migrants from across the globe arrive in New York City, that has been projected to cost the city billions and that has brought the city’s shelter system to its brink, quietly plays out.

The men at Creedmoor come from multiple continents and hail from nations like Venezuela, Senegal and Russia. They say they are all looking for the same things – political asylum and the opportunity to work in the United States.

But their arrival to Eastern Queens was not so simple – the tent shelter was subject to a number of protests, including from a number of elected officials who warned of an undignified life for those expected to be housed there.

Others said they were concerned for the safety of the neighborhood’s residents, and said that they were worried that the migrants would cause havoc in the residential area.

But with the Creedmoor shelter nearly at capacity on Tuesday, most of the concerns shared before the shelter’s opening last week appeared to be unfounded. Most of the men being housed at Creedmoor say they have spent their days either looking for work or not doing much of anything.

An Average Tuesday

On the usually quiet and empty stretch of Hillside Avenue near the shelter on Tuesday, many of the migrant men waited for the bus, others sat and talked at Detective William T. Gunn Playground, others took short walks while some collected recyclables that they would soon exchange for a few dollars. A Little League baseball practice was being held across the street, seemingly unbothered by the neighborhood’s new residents.

Some of the men were smoking or listening to music, and several of them wore the vestiges of New York City’s last major crisis – provided with city-branded COVID gear, several migrants wore garments that read, “I’m an NYC Vax Champ!”

All of the men wore a purple lanyard that held their Creedmoor identification card, which has a photo and a QR code that allows them to enter and exit the HERRC.

Conditions Inside the Shelter

Though quiet on the outside, the situation inside the shelter has its occupants split.

“The food, the bed is super good,” said Yoelvis Chirinos, a 30-year-old Venezuelan migrant.

Fausto David, a 34-year-old from Colombia, agreed.

Two other men, Anton Shkarupa and Pablo Gallago, both Russian migrants in their late 20s who say they came to the U.S. to escape political persecution, said they have had no issues at the Creedmoor shelter, and overall they like it there.

Anton Shkarupa and Pablo Gallago, both Russian migrants in their late twenties who say they escaped political persecution. Eagle photo by Ryan Schwach

“We are grateful to the state and government of New York for the opportunity to live in this shelter,” said Gallago. “There are showers, toilets and [we] are fed three times a day. It's cool at night, so we have to sleep in clothes, but we were in shelters that were worse, where we had to have a place in the room with people who use heroin.”

“Everything here is civil and clean,” he added.

Gallago ate a cheese stick and a hard-boiled egg on a bench at Gunn Playground while speaking with the Eagle. He said both were fresh.

But Merriman Aliaea, who was sitting in the park nearby with three others who, like him, came to the U.S. from Peru, compared the Creedmoor shelter to a prison. He said that there have been some small instances of theft in the shelter, and that he was worried about fights.

Merriman Aliaea, a Peruvian immigrant. Eagle photo by Ryan Schwach

Another man, Gustavo Rafael, a 59-year-old from Venezuela, said he believes there is “a lot of failure” at the shelter, citing what he believes to be cultural incompetence emanating from the staff, who sometimes are unable to solve certain specific cultural issues.

“The mayor is doing everything humanly possible for us to be in a shelter but there are people who do not have the capacity to work with the refugees,” said Rafael. “

Aliaea also said that their purple lanyards, which they are required to wear in and outside of the shelter, have, in some ways, become marks. At least once, a local woman shouted racially charged comments at some of the migrants on Hillside Avenue, Aliaea said.

Despite the sometimes less than favorable conditions, Aliaea said the HERRC is better than some of the alternatives.

“The government did a good job because we don't live on the street, that's a good point,” said Aliaea. “But the point is, here they didn’t make plans for growth.”

Getting to Work

Every migrant at Creedmoor the Eagle spoke with expressed a desire to find quality work that helps them build a new life in the city.

“What many of us need here is a job to be able to rent a room or a house,” said Rafael, who left Venezuela because he said there was no food or work there. “I came to this country for work, not to do bad things.”

“The impediments are the work permit and language,” he added.

This is Rafael’s second attempt at asylum in the U.S., having been previously detained at the border and sent to Mexico, before making his way back again.

“Thank God, I am in the process of seeking asylum,” he said.

Work has been difficult for many migrants to obtain. Most are still waiting for their asylum applications to come back and have been unable to secure work authorization.

Local officials, including Mayor Eric Adams, have called on the federal government to expedite work authorization for the migrants, but those calls have so far gone unanswered.

“It's complicated,” said Chirinos, the 30-year-old Venezuelan migrant. “No papers.”

Yoelvis Chirinos, 30, and Fausto David, 34, both migrants at the Creedmoor site. Eagle photo by Ryan Schwach

Chirinos has been in the U.S for three months, and has been unable to find work. Neither has David.

“We are in the process of getting papers,” David said.

The two were about to go on a short walk, one of the activities men who have been unable to find work do to pass the time at the Creedmoor HERRC.

“We want to get a good job that will help us work to be independent and not in this area,” said Alexander Antonio, who is also Venezuelan. “I’ll cook, do construction, masonry, whatever work they put on me, cleaning, maintenance.”

While Gallago and Shkarupa said they would like to find jobs similar to their careers back in Russia – Gallago was a psychology teacher and Shkarupa was a confectioner – they are mostly looking for any job that will help them settle.

“I’m looking for any job in principle that is suitable for working physical labor,” said Gallago.

While a number of elected officials warned that the site’s distance from the city’s subway system, a local business hub or other areas with work opportunities would impede migrants, they said on Tuesday that without work, the isolation hasn’t been much of an issue.

“It actually doesn’t matter,” said Aliaea, who’s main wish was that he and other migrants be allowed to join the military.

The Q43 bus has become a lifeline for many of the migrants housed at Creedmoor. The bus runs to a number of more populated Queens communities, like Flushing and Jamaica.

However, because most of the migrants have been unable to get the paperwork necessary for gainful employment, their distance from the work itself is inconsequential.

“It's better in Jamaica,” said Rafael. “But since I don’t have a job, it's the same.”

‘No complaints’ but concerns remain

Since the shelter first opened its doors last Tuesday, electeds have begun to tour its grounds to see if their earlier concerns were warranted.

On Thursday, Queens Borough President Donovan Richards made an unannounced visit to the site.

“I went unannounced because I understand that when official tours happen, you'll witness a little window dressing, we didn't want any window dressing,” he said.

But for the most part, Richards said that conditions appeared to be good.

Queens Borough President Donovan Richards made an unannounced visit to the 1,000 bed Creedmoor migrant tent shelter on Thursday, touring the newly opened center. Richards/Twitter

“There were no complaints about the food…the bathrooms were clean, everything is good thus far on that front” he said before adding that he was concerned that conditions would deteriorate as the shelter filled up.

The borough president also said that he was worried what migrants would do during the day as more and more are brought to the site.

“We raised the point of ensuring that these individuals can have access to perhaps Queens Library, we need to really wrap the site around with service, otherwise, you're going to have loitering in the neighborhood because when people have nothing to do, [they loiter]” he said. “You can't say, call the NYPD, we saw them walking through the neighborhood. Just because they're migrants doesn't mean that they don't have the right to go to the park.”

However, Richards says he was inspired by what he saw.

“I saw hope, I saw individuals who want to fulfill the American Dream, that's why they came here,” he said.

Earlier this week, other Eastern Queens electeds, including Assemblymmeber Ed Braunstein and City Councilmember Linda Lee, also took an organized visit to the Creedmoor shelter.

Lee said a number of her concerns remain.

“There are issues that remain surrounding security, school safety, and transportation access that we are actively working to address with the shelter,” Lee said in a statement to the Eagle. “The shelter has been receptive and cooperative, but some of these issues still remain that we are actively working to address in the coming days.”

Abdoulaye Ba, a 25-year old migrant from the Western African nation of Mauritania. Eagle photo by Ryan Schwach

Lucky Ones

As the asylum seeker crisis is expected to continue to mount in New York City, a number of those housed at the Creedmoor shelter said they were managing their day-to-day lives and said they’d continue to look for work, despite the hurdles they’ve had to face.

Ndoye, the 40-year-old from Senegal, said that he was one of the lucky ones, having been able to find some semblance of work.

It gives him hope for the future.

“I want to live here because I left my family back there, I want to bring [them] one day,” he said, before getting on an already-crowded Q43 bus. “For now, it's ok, you have to endure.”