Queens court interns hear wrongfully convicted man’s story

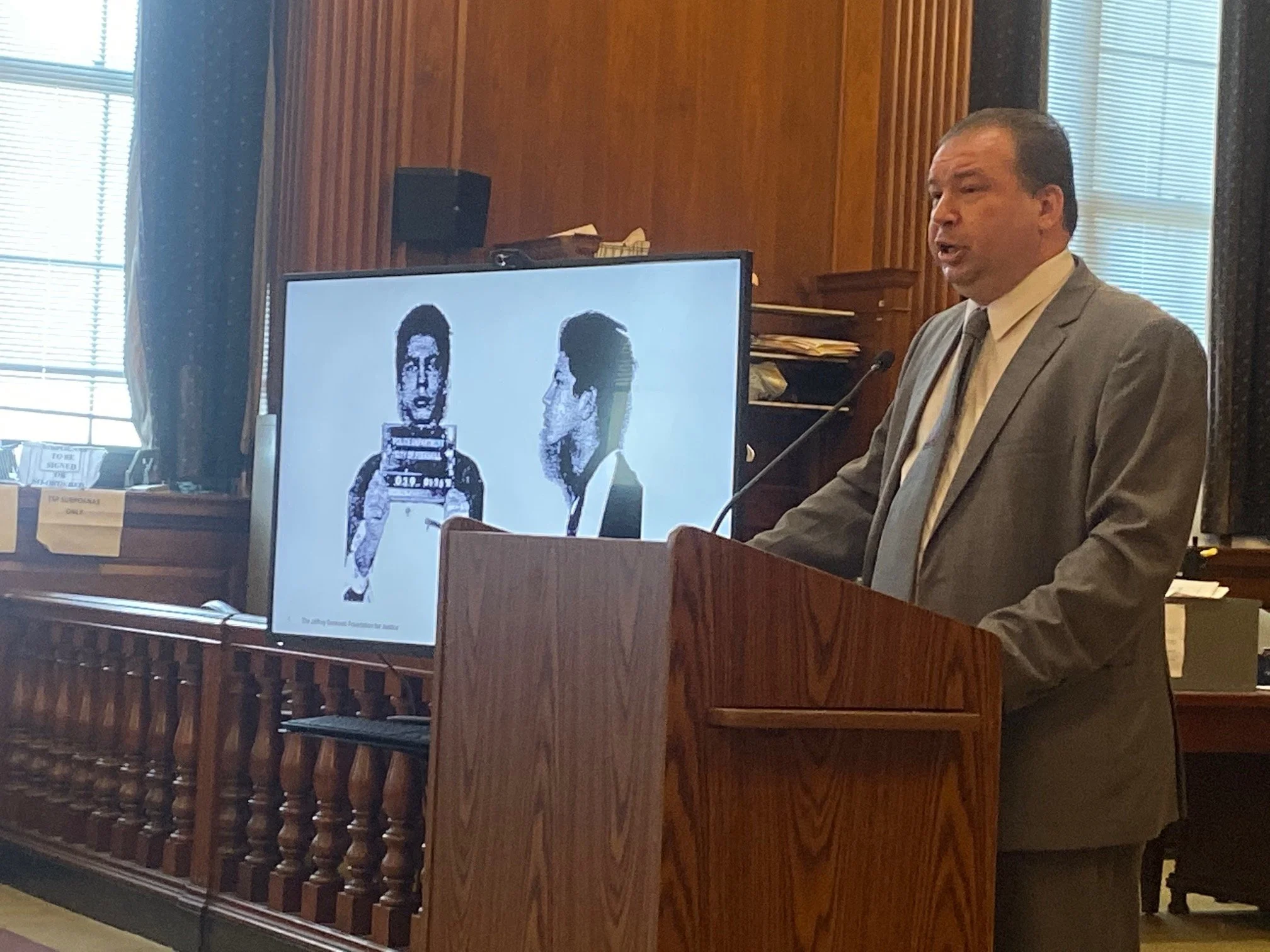

/Wrongfully convicted man, turned justice advocate and lawyer Jeffrey Deskovic speaks at Queens Supreme Court, Civil Term next to his mugshot from when he was arrested in the 1980s. Eagle photo by Ryan Schwach

By Ryan Schwach

When he was just a teenager at Peekskill High School in the late 1980s, Jeffrey Deskovic was wrongfully convicted and imprisoned for the rape and murder of a classmate. He served 16-years in an upstate prison before DNA evidence exonerated him.

Now, he advocates and fights for others who are wrongfully imprisoned and for a number of criminal justice reforms. On Friday, he spoke to a group of court interns at Queens Supreme Court, Civil Term about his story, and the work that he does to help obtain justice for others.

In 1989, when Deskovic was 16 years old, a classmate, Angela Correa, was found raped and murdered at a park. Murders were rare in the small town of Peekskill in Westchester County.

“When this murder happened, it created an atmosphere of fear, rumor paranoia,” said Deskovic, who attended Correra’s funeral.

During the ceremony, he cried, which made the police suspicious, he said.

“I was a sensitive kid,” Deskovic said on Friday.

For several weeks, two detectives formed a relationship with Deskovic, asking him questions, asking for his opinion, and ingratiating themselves with the teen who at the time aspired to become a cop. It was a game of “good cop, bad cop,” as Deskovic described it.

After about six weeks, he was taken to the neighboring Putnam County to take a lie-detector test, where he was not fed, and spent several hours being given coffee.

“He gave me countless cups of coffee,” Deskovic said. “He ultimately gave me somewhere between six to eight cups of coffee, so he metaphorically wired me up.”

After hours of what Deskovic described as leading questions and verbal abuse, he gave a false confession, and was immediately booked for the rape and homicide of his classmate.

“I wasn’t thinking about the long term, I was just concerned with my own safety in the moment,” Deskovic said.

During his trial, where he says he was improperly represented, DNA evidence that would have proved he wasn’t there, was withheld, and ultimately, he was convicted and sentenced to a life in prison.

“At 17 years old…I was frightened,” he said on Friday.

For 16-years, Deskovic worked from his prison cell in Elmira, trying to find ways he could get his case heard again, and his conviction overturned.

Eventually, his case was taken up by the Innocence Project, who pushed through red tape in getting the DNA evidence back into the courtroom, which was previously denied. The work led to his eventual release and exoneration in 2006, as well as the arrest of the real killer.

Wrongfully convicted man Jeffrey Deskovic speaks with interns following his talk at Queens Supreme Court, Civil Term. Eagle photo by Ryan Schwach

“It was very strange to put your life back together again after going through a traumatic experience,” Deskovic said.

After getting his GED and beginning a bachelors while wrongfully imprisoned, Deskovic finished school at Mercy College, got his masters degree at CUNY’s John Jay, got a law degree and started the Deskovic Foundation, which works to overturn wrongful convictions.

During his talk in Queens on Friday, Deskovic spoke about legislation currently in the pipeline, as well as other measures that could be made to prevent cases like his from happening in the first place.

He encouraged the governor to sign the Challenging Wrongful Convictions Act, which the legislature recently passed and which would open up new pathways for incarcerated New Yorkers to challenge their convictions.

He also talked about three bills that would help prevent and protect youth against false confessions. The various bills would require that police record interrogations with minors and that would explicitly prevent police from deceiving a suspect about a case.

“Kids…they don't understand their rights,” he said.

Giving talks to students, he said, helps prepare youth for the court system, should they find themselves entrenched in it in any capacity.

Deskovic with court inters. Eagle photo by ryan schwach

“I think it's important to teach kids, what are their rights? When will you be read the Miranda warnings? What does that actually mean? What's the importance of not waiving your rights? I think that's important,” he said. “I think we need to raise awareness about wrongful convictions in general.”

“I think that all those things are important in trying to understand the legal system,” he added.

On Friday, Deskovic told his story to a group of interns in the courts, who are learning about all the different roles within the court system, not just lawyers and judges.

“We wanted people to see these different careers in the courts, not just being a lawyer or a judge but the many things that they can do,” said Maria Bradley, the chief court attorney at Queens County Supreme Court, Civil Term.

Bradley says that this opportunity was a special one for the students, as well as the court.

“It's very unusual for us to have anything about criminal law here in Queens Supreme, Civil but fortunately we had this opportunity to hear this amazing story,” she said.