DAs quietly push discovery rollbacks in Albany

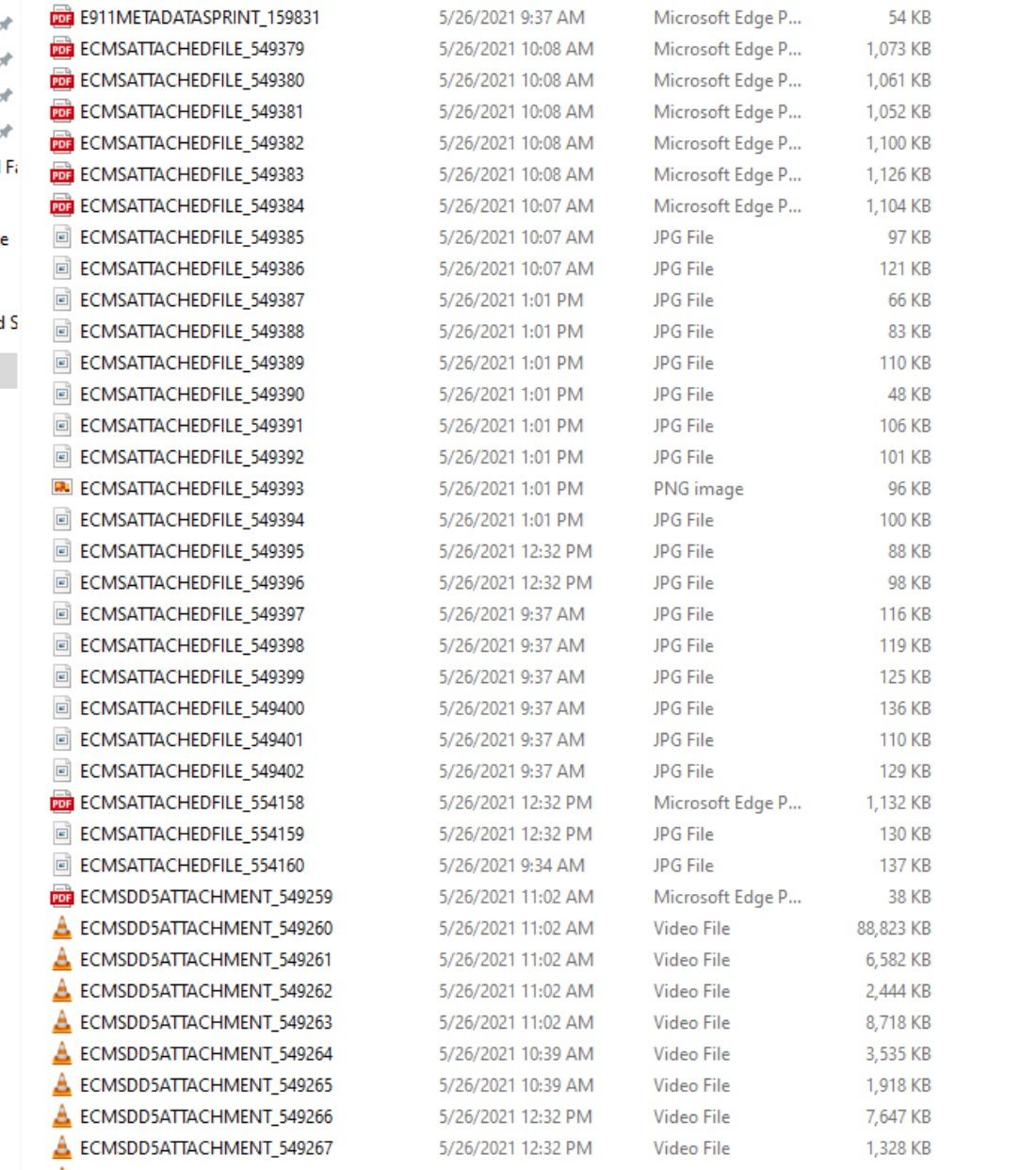

/An example of a discovery file shared by the Queens district attorney’s office with a defense attorney. Screenshot via legal aid society

By Jacob Kaye

Several New York City district attorneys are pushing leaders in Albany to include rollbacks to the state’s discovery reforms into the state’s budget, sources with knowledge of the negotiations told the Eagle.

At least one of the changes, none of which have been formally presented to the public, has recently picked up steam in Albany, and could potentially be included in the state’s fiscal document, which is now two-weeks late and has mostly been held up by a separate negotiation over the state’s bail laws.

Several public defense firms decried the proposals on Wednesday, calling on legislators to reject the changes to the 2019 discovery reforms that they say will “return New York to a time when crucial evidence was withheld from the defense and our clients languished on Rikers Island for years.”

“This 11th hour ploy to gut one of the most transformative reforms Albany has codified in recent memory is a shameless attempt by prosecutors to revert back to the days when discovery practices skewed heavily in their favor,” the Legal Aid Society said in a statement. “If passed, this proposal would upend the criminal legal system and further the disparate outcomes that our clients, Black and Latinx New Yorkers, would have to bear.”

The three-pronged proposal to rollback the 2019 reforms comes from Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, Bronx District Attorney Darcel Clark and Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez. Both the Brooklyn and Bronx DA declined to comment for this story.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Bragg said: “We are continuing to work with our partners in Albany to find commonsense solutions that preserve the intent of the law while ensuring we can achieve appropriate accountability in all our cases.”

Queens District Attorney Melinda Katz did not sign onto the proposals but a spokesperson for her office said that she supports the measure.

Katz, who took office just as the reforms were passed into law, has often credited the reforms for heavily contributing to her office’s attrition rate, which, while not as high as other New York City prosecutors offices, has seen an uptick in recent years.

At least one of the proposals is making headway in Albany, according to a source with knowledge of the proposal.

The change would require that defense attorneys submit a motion challenging a prosecutor’s “certificate of [discovery] compliance” within 35 days or waive their right to challenge it at any other point.

Under current discovery laws, prosecutors must submit all evidence they have against a defendant to that defendant's attorney within a set time frame. Once they do, they can file a certificate of compliance and declare that they are ready for trial. Currently, the burden to turn over evidence rests solely with the prosecution.

Under the proposal, at least part of the burden of ensuring that all evidence is turned over to the defense would fall on the defense itself, who would be required to identify pieces of evidence they have not yet seen and request it through a motion.

By filing the motion, the speedy trial clock – which is 90 days after an arraignment for a misdemeanor and six months after an arraignment for a felony – would stop, granting prosecutors more time to compile their evidence, public defenders argue. The clock wouldn’t again start until the motion is ruled on, which could be several months after its filing.

The public defenders argue that the change would allow prosecutors to turn over a portion of the evidence and either force defense attorneys to file the motion, stopping the speedy trial clock, or risk waiving their rights to force prosecutors to turn over any additional evidence before trial.

“Legislative changes to undermine the discovery laws will diminish prosecutorial accountability, result in more wrongful convictions, and cause more New Yorkers to languish in deadly jails for longer,” Brooklyn Defender Services said in a statement.

“Lawmakers must reject the governor’s and prosecutors’ attempts to weaken the discovery laws, and instead fulfill the promise of these laws with proper resources,” they added. “New York cannot go back to the Blindfold Law.”

A spokesperson for the governor declined to comment specifically on Hochul’s support of the proposal and instead directed the Eagle to comments Hochul made about discovery reform last Wednesday.

“We've been talking about public safety in general...and we'll be looking forward to continuing making progress on public safety,” Hochul told reporters.

When asked again if she was looking to make any changes to discovery reforms, Hochul said: “We're looking at public safety.”

Prior to and in the years after the reforms passed, prosecutors throughout the state have argued that the laws are too burdensome, and have increased the workload of prosecutors to an untenable degree.

Public defenders have, for the most part, agreed. But while public defense firms have called on the state to better fund discovery work for both the defense and prosecution – no funding mechanism was included in the original reforms – prosecutors have instead called for an overhaul of the laws.

In her executive budget, the governor included an additional $40 million for prosecutors’ offices to go directly to discovery work. While discovery work funding for public defenders was also included in the governor’s budget proposal, it was nearly six times less than the proposed funding for prosecutors.

“Funding is actually the solution that would allow discovery reform to fulfill its intended goal,” the Legal Aid Society said in a statement.

“The 2019 reform failed to include resources to help both District Attorney Offices and public defender organizations implement the wholesale change in evidence sharing practices,” they added. “Instead of turning back in the face of difficulty, Albany should instead allocate the funds needed in the upcoming budget.”

The state’s reformed discovery laws went into effect in 2020, speeding up the timeline in which prosecutors are required to share evidence with defense attorneys. The reforms, which have been amended twice since they first went into effect, also expanded the list of materials prosecutors were required to share.

Prior to the changes, defense attorneys said that prosecutors would wait, in some cases, until the night before a trial to share the evidence they had against a defendant. By withholding evidence until the last possible moment, prosecutors had more sway in securing plea agreements and held a tactical advantage if a case went to trial, reform advocates said.

Under the reforms, prosecutors are required to share evidence within 20 to 65 days of a defendant’s arraignment, depending on the case.

However, public defenders say prosecutors more often than not turn over evidence closer to the 60-day mark, or don’t meet the deadline at all. Defense attorneys say there isn’t much consequence when a prosecutor misses the deadline. Cases are not thrown out until prosecutors are out of compliance with the speedy trial clock.