Inside the Queens Defenders’ Youth Court

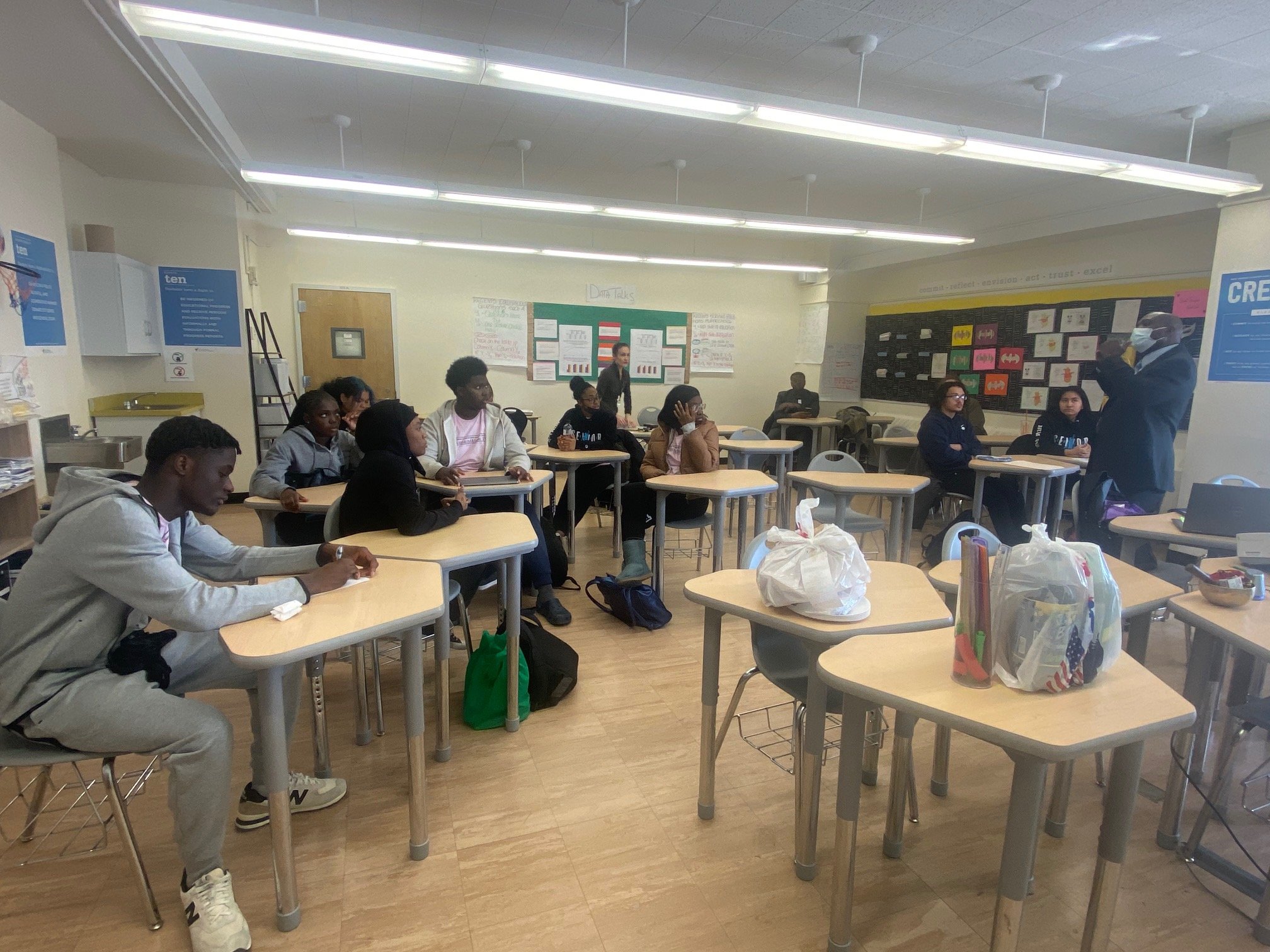

/New Visions Charter high schoolers in Rockaway attend the Youth Court program and learn about the judicial system . Eagle photo by Ryan Schwach

By Ryan Schwach

It is not a courtroom on Sutphin Boulevard in Jamaica or Centre Street in Manhattan – it is a classroom on Beach Channel Drive in Rockaway Beach.

The members of the defense and prosecutorial team are not law school graduates – they haven’t passed the bar, let alone the SATs. The cases do not concern homicide or housing, they concern vaping during school hours and talking during class.

The Queens Defenders’ Youth Court Program at the New Visions Charter School at the Beach Channel Educational Campus brings a small group of students together to solve small cases within their school building, in an effort not only teach students about the judicial system, but to also help the young “defendants” learn from their mistakes without staining their record with a minor infraction.

“The Youth Court program is based on principles of restorative justice, where you want the young person to take responsibility for their actions and then have them figure out how they can make amends,” said Kirlyn Joseph, the program’s director. “It’s never about punishment.”

“If we can intervene, identify what the issues are and address them, then we save the state and this city thousands of dollars that would be spent on dealing with a case in court, or even ultimately incarceration,” she added.

The program has existed since around 2013, and is held at various libraries and schools around Southeast Queens. The program's organizers say it helps the students whose cases are being heard as well as the participants.

“I think the most important role is just helping to develop well-rounded young people who can look at a situation or a case from many different points of view,” Joseph said. “But I think we could see from the young people, not only the participants, but also the young people whose cases were referred, that we were making a big difference, if for no other reason than giving all of them an opportunity to be heard.”

Alliyah St. Omer began the program in her freshman year of high school. Now a junior in college and senior leader in the program, Omer is looking to a career as a defense attorney.

“I thought it was really cool,” Omer said. “Instead of letting kids go through the system or just be told, ‘You did something wrong,’ and, ‘Ok don’t do it again,’ take accountability for their actions and figure out a better way to address them.”

“It was something I've never seen before,” she added.

Omer remembered a case where a student was caught drawing graffiti, and rather than face a penal punishment, he was asked to write a letter of apology and use his artistic abilities to create a piece that could be hung up in the Far Rockaway library.

“You never know the kind of case that we were gonna get or you never knew the impact that potentially we were making,” Joseph said.

At New Visions, a group of students, a mix of volunteers and students selected by the administration, spend their afterschool time on Thursdays learning about the judicial system and hearing cases.

“Here in New Visions High School, it's a restorative approach,” said Nick Hillary, the program’s facilitator. “So we teach them how to make an argument. We teach them how to be critical thinkers. We teach them aspects of the criminal justice system to get their views on a criminal justice system.”

Hillary himself faced the complications of the legal system when he was falsely accused of murdering a 12-year-old boy in 2011, and uses what he has learned through his own experience to teach kids about the system and how to argue on one another’s behalf.

“I spent a solid decade plus litigating in my situation, which opened up my background to the legal aspects in a lot of the intricacies in the law,” he said.

At New Visions, Hillary teaches the kids how to make a reasoned argument and represent their peers in a fair and accurate manner, or in a manner that maybe only a fellow teenage student could understand.

“When you have kids looking at other kids and viewing it from this perspective, sometimes they have a better understanding as to underlying issues,” he said. “A student might not be having the best day, as they themselves oftentimes don't have their best day. So having someone who's actually walking the path to come up with a resolution and to assess someone else [is important].”

But beyond the students serving as officers of the court, the students who are brought before the court may be receiving an even larger benefit.

“That stigma of a student even being picked up by a school resource officer and then later on for something minuscule, it compounds and becomes an avalanche that later on affects the student going forward,” he said.

Recently, the students started work on a new case. A student in the school was speaking and making noise during a lockdown drill, even after being told to stop.

The case was referred to the Youth Court through the teacher and the school’s administrators.

Hillary split the class in two, a prosecution group, and a defense group. He took turns guiding each, helping them better articulate their arguments.

“I like the restorative justice part,” said Marcia Hayes, a New Visions student who was part of the team coming up with the student’s defense. “I like how we get to get involved in things that happen in our school, especially, we want to help our other students who face any punishment or consequence for any thing that they've done.”

Hayes and her group made the argument that it was possible the student wasn’t aware of the expectations of the drill, and that if he did commit the infraction then the punishment should be less severe. In turn, the prosecution planned on calling the teacher and the student to the stand. The trail will commence in the coming weeks.

“I would say it takes a lot of responsibility,” said Tyler Agyarko, another student. “But it feels like making the right steps to understand where the situation could be.”

For both Agyarko and Hayes, the program allows them to play a part in their school, and help fellow students.

“[The students’ voices are] actually heard…it's not that all problems need to be dealt with by the administration and the hardest consequence, some problems could easily be fixed with restorative justice, especially with the help of their peers,” Hayes said.

Hayes and Agyarko are both considering careers in law, partially thanks to the program.

“This has helped me get a better understanding,” said Hayes. “Because I do want to be a lawyer in the future, maybe not criminal, but I still want to be able to help people.”