Conditional release commission has no commissioners

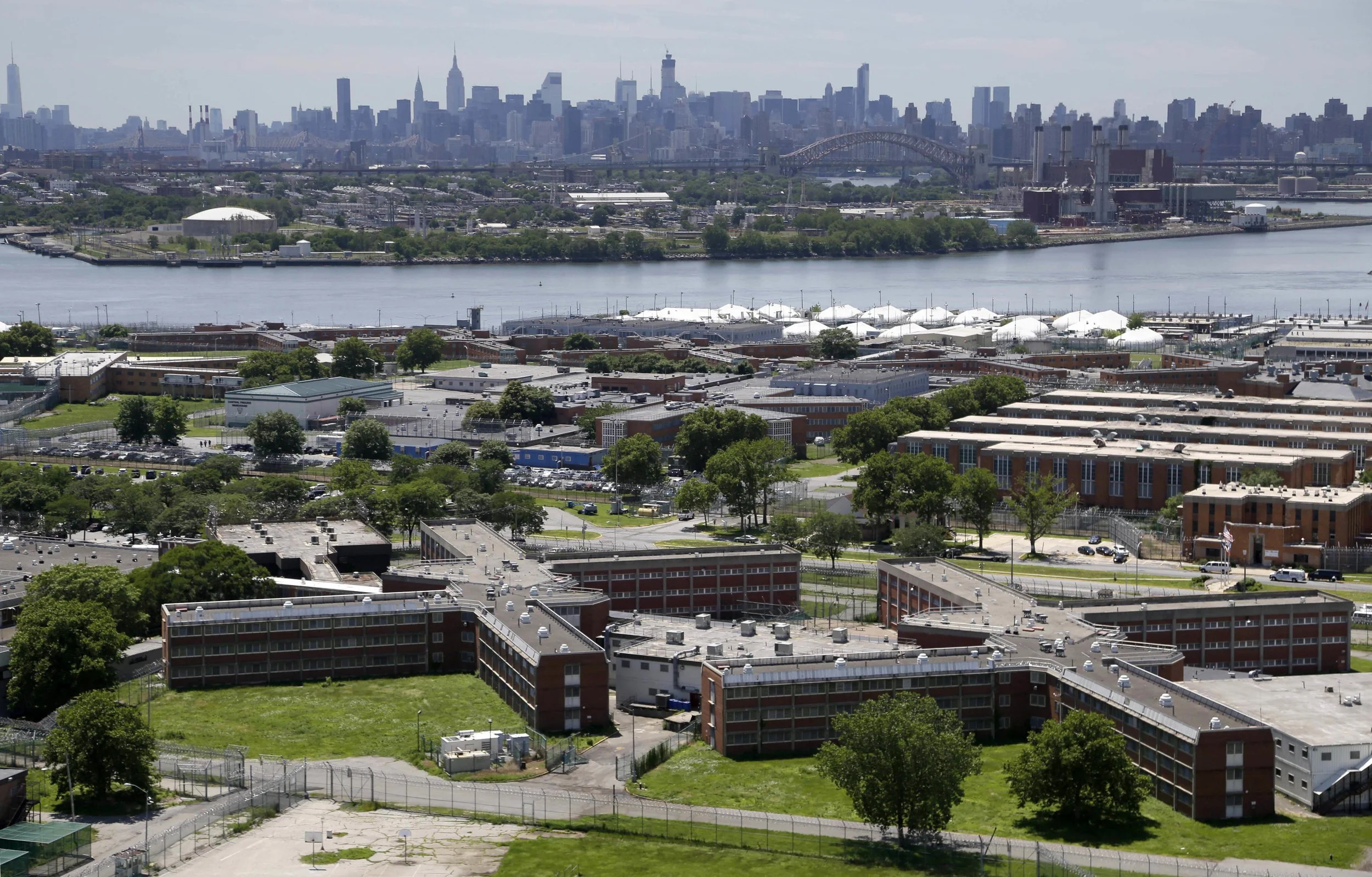

/The Local Conditional Release Commission was created in 2020 to screen potential candidates for early release from Rikers Island. It has yet to have a single commissioner appointed to it’s board. AP file photo by Bebeto Matthews

By Jacob Kaye

In 2020, just as the pandemic was beginning to amplify a multitude of crises on Rikers Island, the City Council created a commission tasked with helping to lower the population in the city’s jail.

Two years later – including one year that saw 16 detainee deaths – the city’s Local Conditional Release Commission, which would screen potential candidates for early release from a city sentence, is without a single commissioner and has yet to hear a single case, the Eagle has learned.

Though a number of names were submitted to the former mayoral administration in 2021, no action was taken to appoint commissioners to the body, which could potentially grant the release of around 100 detainees serving short sentences in the city’s jail per year. Mayor Eric Adams’ administration has yet to appoint anyone, leaving the commission bare and leaving a number of potential candidates locked up in the jail in crisis.

“I’m not sure what the root cause of the delay is,” said City Councilmember Carlina Rivera, who chair’s the council’s Committee on Criminal Justice. “I just know that it's one of many important steps that we have to take to reduce the overall jail population.”

“I think it's been made very clear through stories and experiences from people currently or formerly incarcerated at facilities like Rikers that the conditions there are nothing short of a humanitarian crisis,” she added.

‘This isn’t a free pass’

The Local Conditional Release Commission was created in June 2020 through a City Council bill. Former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s support of the commission wasn’t explicit – he returned the bill to the council unsigned, allowing it to pass into law without his signature.

It was created at a time when city officials were not only trying to stem the spread of COVID-19 in the city’s jails, but also as they were working to slowly lower the jail’s population in anticipation of the eventual closure of Rikers.

When it’s up and running, the commission’s five yet-to-be named appointees would consider detainees to be released early. However, there are a number of conditions incarcerated people first need to meet.

Though the commission is an independent body, it works in tandem with the New York City Department of Probation. The department’s commissioner, Ana Bermudez, will serve as an ex officio, non-voting member of the commission. Once a person is granted conditional release, the probation department will monitor and provide a number of services, including housing, employment and substance abuse support, to that person for a year.

There are also a number of conditions a person must meet while out on release. Any violation of those conditions will land the person back in jail.

"They are not receiving a get out of jail free card – they actually have to abide by the conditions imposed by the CRC; and will receive services provided by [the Department of] Probation for one year; and if those individuals are found in violation of those terms, they go back to jail,” said Wayne McKenzie, the general counsel for the Department of Probation. “This isn't a free pass at all."

Detainees considered for release will have to be serving their sentence in the city’s jails – not at a state prison facility. The sentence will have to be longer 120 days and they will have to already have served 90 days of that sentence.

Additionally, there are a number of conviction charges that could make the person ineligible for consideration, including domestic violence or a sexual offense. The detainee would also have to demonstrate they’ll have some sort of tie to the community upon their release, be it employment, a permanent residence or family, among other requirements.

An under-the-radar Local Conditional Release Commission isn’t new to New York City.

A previous iteration of the body was created in 1989, when crime rates skyrocketed and the city’s jails began to fill up. Throughout the following decade, the commission released hundreds of people held on low-level offenses each year. But as crime rates fell in the early 2000s, the commission’s workload fell with it.

In 2004, the commission, which operated without much oversight or attention, came under scrutiny when it was revealed they had released a number of government officials convicted of public corruption and a New York Jets player jailed for domestic violence. The releases prompted an investigation from the Department of Investigation, which recommended that then-commission and head of the Board of Correction Raul Russi resign from the BOC.

In light of the scandal, the state law that mandated local conditional release commissions existed throughout the state was altered to allow localities to choose whether or not to use one. New York City allowed its commission to die.

The commission returns

A little over a year after the current iteration of the commission was created, it got its first hire. Roberto Velez, who previously served as commissioner of the Department of Probation, was brought on to serve as the commission’s executive director in October 2021 – the same month Bermudez and McKenzie were asked to testify on the status of the commission before the council’s Committee on Criminal Justice.

Roberto Velez was named the executive director of the Local Conditional Release Commission in October 2021. He remains the only person on the commission. Photo via LinkedIn

“We’re disappointed it’s not up and running,” Councilmember Keith Powers, who previously served as the committee’s chair and who now serves as the majority leader, said at the hearing. “I'm not getting enough information here today.”

Though the Mayor’s Office of Appointments was allegedly invited to testify at the October hearing, no one from the office showed up to explain the delay to bringing commissioners on board.

Zachary Katznelson, the executive director of the Independent Commission on New York Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, said that for the nearly two years since it was created, the commission has been sorely needed.

“Right now, what happens is that people are going straight from the maelstrom, the cauldron of violence and dysfunction at Rikers, and coming straight back into the community, often without sufficient support,” Katznelson told the Eagle.

“The Conditional Release Commission would allow us to look at people as individuals, and say, ‘How do we ease somebody to transition them back into the community successfully so that they have the best chance to thrive, and also the least chance of ever coming back to Rikers,’” he added. “It's unnecessary to have this many people locked up – there are better ways to ensure safety.”

Political pressures

Without the commission, there are few other mechanisms for conditional release in the city.

At the start of the pandemic, de Blasio released nearly 300 Rikers detainees through the 6A program, which allows for detainees serving a sentence of less than a year to be sent home on work release. But after the initial push, 6A releases dried up.

In 2021, six people were released under the work program, according to a Department of Correction spokesperson.

In September of last year, as calls to utilize 6A intensified and as crime rates climbed throughout the city, de Blasio also faced mounting political pressure to take a harder stance on public safety.

"My position would be people that are in there deserve to stay in there," former Police Commissioner Dermot Shea said about the 6A program at the time, NY1 reported.

The same pressure could have affected appointments to the Local Conditional Release Commission, which wasn’t popular among the city’s District Attorneys. During a 2020 City Council hearing, nearly every DA testified personally or through a representative in opposition to the commission.

“It is the district attorney's position that the parole board is uniquely situated to make the most informed determination for conditional release,” said Jennifer Naiburg, the chief assistant district attorney under Queens District Attorney Melinda Katz, during a 2020 City Council hearing. “History…has proven that local conditional release commissions are not the better choice in making these critical determinations.”

In a statement to the Eagle, a spokesperson for the Queens district attorney’s office said: “We expressed our concerns before the City Council created the commission in 2020, notably about the troubles of the city’s previous commission.”

“We hope that those concerns will be addressed as this effort moves forward,” the spokesperson added.

Around 100 detainees who meet certain criteria could be released from Rikers Island each year by the Local Conditional Release Commission if it had commissioners. AP file photo by Seth Wenig

Similar political pressures remain. Adams built his campaign and the first months of his mayoralty on a tough on crime posture. He has advocated for reforming the state’s bail laws and has called for judges to be granted the discretion to set bail on someone based on their perceived danger to the community.

However, advocates say the Local Release Commission falls squarely into what Adams claims is his balanced approach to public safety.

“This program is really about scrutiny of peoples’ release plans, with public safety front and center,” Katznelson said. “The point really is how do we stop someone from ever coming back?”

“If they do a few more months at Rikers and are subjected to violence, that's not going to make them more successful,” he added. “The mayor talks a lot about prevention and intervention – this really blends the two of them incredibly well.”

Rivera said that she’s unlikely to hold a second hearing on the status of commission, but would soon be meeting with Bermudez to discuss ways to begin to appoint commissioners. She also said that she hopes to speak more often with both Bermudez and the Mayor’s Office of Appointments as the commission approaches its two-year mark.

“There has to be communication there,” Rivera said. “Submitting the list, we can’t just throw up our hands – we have to figure out why there's been a delay and why two years later there could have been some sort of significant improvement, and we could have learned a lot.”

McKenzie told the Eagle that he expects appointments are coming soon.

“As the previous administration did not appoint any CRC members, the new administration, which has been in office for a few weeks, will consider and appoint members," McKenzie said.

Adams, who has been mayor for a little over two months, and his administration have had to consider candidates for hundreds of positions since he first took office – major appointments remain unfilled, including a sanitation and fire commissioner. The backlog of appointments, a problem faced by every incoming administration, might be to blame for the further delay according to Katznelson.

“I think the current administration has had to grapple with just getting everybody in place,” Katznelson said. “As they've started to get those people in their positions, now is a chance for them to be able to turn to things like the Conditional Release Commission and hopefully start to vet and appoint people in the coming months.”

The mayor’s office did not respond to request for comment.