School Policing Budget Spike Is Fuel for School-to-Prison Pipeline, Activists Say

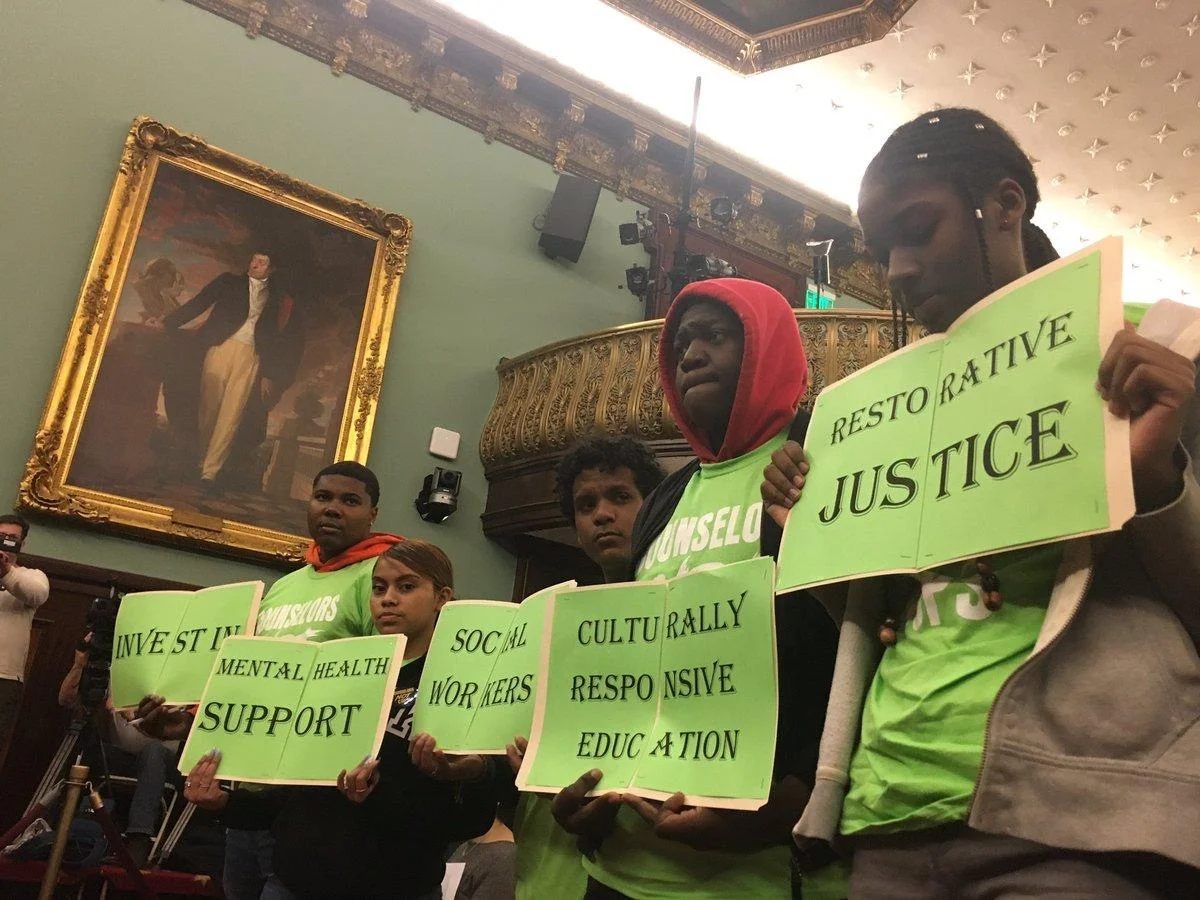

/Students from the Urban Youth Collaborative demonstrate at a budget hearing in City Hall. Photo courtesy of Charlotte Pope

By Jonathan Sperling and David Brand

Teachers, social workers and high school students gathered at City Hall Wednesday to denounce a $27 million funding increase for school policing included in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Fiscal Year 2020 preliminary budget. The increase would inflate the NYPD’s School Safety Division budget to $314 million, the largest amount in its history.

Activists say that will lead to the over-policing of young people, especially young people of color, and divert issues that could be handled within schools to the criminal justice system. The coalition calls for the city to divest from the School Safety Division and direct the leftover funds to hiring more guidance counselors and social workers.

“We believe that the city should be investing in support like guidance counselors and support staff, not things that criminalize young people of color in schools,” Dignity in Schools Campaign Director Kate McDonough told the Eagle. “The School Safety Division is under the NYPD, so that is the funding of police in schools. It does lead to the over-policing of young people of color in our school system. Black and Latinx students make up the majority of detentions and suspensions in schools.”

Despite the early morning start, McDonagh said the energy was high at the rally, where wore shirts that read “Counselors Not Cops.”

The demonstration was “very powerful” and “intergenerational,” McDonagh said.

An analysis by the New York Civil Liberties Union last year found that Black and Latinx students account for approximately 90 percent of arrests and summonses in New York City schools, despite comprising roughly two-thirds of the student population. Black and Latinx students accounted for 93 percent of juvenile reports and 94 percent of mitigated incidents involving handcuffs, according to the NYCLU.

Dignity in Schools depicted their goal of funding more than 14,700 social workers and guidance counselors by 2023. Graph courtesy of Dignity in Schools

“We’re calling for the funding of restorative justice. Investing in restorative justice is investing is something that has been proven to benefit schools,’ McDonough said. “There are more school safety agents than school guidance counselors and social workers combined.”

The issue of school policing also came up at a Queens District Attorney candidate forum hosted by CUNY Law on March 12. Andrea Colon, a community engagement organizer with the Rockaway Youth Task Force, asked the six candidates who attended the event to describe their positions on school policing.

“Police in schools do not make students any safer,” Colon said. “What actions will you take to end the school-to-prison pipeline here in Queens?”

Candidates answers ranged from totally denouncing police in schools to saying the DA’s office has no impact on the issue.

Former state Attorney General’s Office prosecutor Jose Nieves said “schools, public and otherwise, are over-policed” and added that he would “treat kids like kids.”

“When I step into Franklin K. Lane [High School], it reminds me of Rikers Island,” he said of his alma mater. “There are metal detectors, blue uniforms. It has the feel of an institution.”

“We need to make sure our kids are diverted from the criminal justice system and given the opportunity to turn their life around and not be saddled with a criminal conviction for the rest of their life,” he continued.

Borough President Melinda Katz recalled her time as a student at Hillcrest High School, when a stabbing prompted a police presence in the school.

“It had such a dampening effect on the entire school when police officers were walking in the hallways,” Katz said, adding that she would fund diversion programs and services that match students with mentors. “If we do have police officers in schools, we have to make sure they’re reacting to something. It can’t be a regular thing.”

“I absolutely think there are too many police officers in schools,” she continued. “The reason is diversion programs are not working to the fullest extent that they can.”

Councilmember Rory Lancman cited programs that he has helped fund through the City Council and said he would not prosecute most offenses aside from “serious violence.”

“The next DA has to take it upon himself or herself to end the school-to-prison pipeline,” Lancman said. “As DA, we are not going to be prosecuting these low-level offenses that come out of schools: scuffles, vandalism, kids acting out. Those should be handled inside the schools with guidance counselors, not with prosecutors.”

Attorney Betty Lugo said her own experience in high school and as a defender positioned her to carefully consider school policing. Lugo said boys used to turn off the lights in a basement music class and molest girls in the dark room.

“I said I wouldn’t go to class unless you police that activity,” she said she told the principal.

She said she also defended a student who brought a box cutter to class because his mother did not speak English and did not understand the teacher’s instructions about a school project.

“All she understood was that he needed to bring a boxcutter to do a project,” she said. “They were going to suspend him but they didn’t because someone had the money to hire a private lawyer.”

“The DOE should handle these cases,” she continued. “If it’s a violence case where someone is violently injured, then it should go to the police and the DA’s office.”

Former Judge Greg Lasak said it was not the DA’s place to take a stand on school policing, but added that he would expand programs that “bridge the gap” between communities and courthouses.

“The DA’s office has nothing to do with why [police] are there,” Lasak said. “If the Department of Education wants them there, that’s their business.”

In contrast, public defender Tiffany Cabán took a strong stance against school policing.

“We need to get police officers out of our schools,” Cabán said. “We need to get rid of things like ‘zero tolerance’ that is weaponized against certain communities, against low-income black and brown communities, and engage in restorative justice — divest from prosecuting and invest in our schools.”

Mina Malik, a former Queens assistant district attorney and Civilian Complaint Review Board director, was sick and did not attend the forum.