Part I: Diverse Immigrant Communities Unite to Preserve TPS

/Journey for Justice participants advocating to save TPS. Photo courtesy of the National TPS Alliance.

By Irvis Orozco

Special to the Eagle

Erika Suarez is tired of the lies, but she has no time to argue. Her family’s future is at stake in the United States.

“I was not brought here willingly,” the 25-year-old Southern California resident says. “I was brought here because of U.S. imperialism. I was brought here because the USA paid El Salvador’s government to torture and kill its own people. I was brought here because the USA began a gang epidemic in El Salvador. I was brought here because the USA is still interfering with El Salvador’s economy for the sake of cheap labor. Let’s get that clear. My mom ain’t no criminal. Our parents just ran out of options.”

Suarez is one of the 704,000 DACA recipients living in limbo since the Trump administration announced an end to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program in September 2017.

For Erika’s mother, Maria, 54, originally from Lourdes, El Salvador, life could come to a halt if Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is taken from her. She has been a TPS holder for almost 18 years and pays $495 to renew it every 18 months. Like many other Salvadorians, she immigrated to the United States because of economic and political turmoil in her home country and the devastating earthquakes in 2001 that left the country’s infrastructure broken.

“The situation in El Salvador comes with a lot of insecurity because of the country’s problems, with violence and the gangs,” Maria explains. “After the 2001 earthquakes, the power of gangs in El Salvador drastically increased.”

Maria works for Los Angeles County as an in-home care provider and needs TPS to work in the U.S. legally. “We need the chance to stay here permanently,” Maria says. “We are helping the country by working. Ever since I came to the country, I have always done and paid my taxes.”

El Salvador was the first country to get TPS, a form of humanitarian legal relief designed to give temporary status and work authorization for immigrants fleeing war, conflict-ridden areas and natural disasters. Congress granted TPS through the Immigration Act of 1990 to protect Salvadorans escaping their country’s civil war. After the designation expired in 1992, the Bush administration gave El Salvador TPS again in 2001. Since then, the U.S. government has renewed the status and today provides TPS to over 300,000 people from 10 countries: El Salvador (195,000), Honduras (57,000), Haiti (50,000), Nepal (8,950), Syria (5,800), Nicaragua (2,550), Yemen (1,000), Sudan (450), Somalia (270) and South Sudan (75-200).

In January 2018, President Trump announced plans to end TPS for four countries: Sudan, Nicaragua, Haiti and El Salvador. The expiration dates are fast approaching.

Maria is scared that she could lose her job and, if sent back to El Salvador, would have difficulties finding employment because of her age. Maria has her work permit until September 2019.

For now, a federal judge’s decision in San Francisco in October has blocked Trump’s plan to end TPS, giving Maria and impacted TPS holders a reprieve.

But TPS is under more political scrutiny as over 7,000 people have fled Honduras, traveling north in a migrant caravan. The caravan—and whether to allow it into the United States—is creating a heated debate between anti-immigrant and immigrant advocates. What gets less attention is the U.S. role in the Honduran exodus and how American policy of economic development in Latin America has made poverty and violence worse.

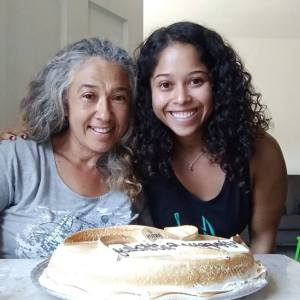

Erika, right, and her mother, Maria. Photo courtesy of Law At The Margins.

The United States has a long history of interventions that have caused instability in Latin America. During El Salvador’s civil war in the 1980s, the U.S. military funded and trained death squads. The U.S. opposed democratically elected Salvadorian governments, installing a right-wing government to commit butchery in a “dirty war.” U.S. allies kidnapped children from peasant settlements and sometimes forced them to fight guerrilla groups. The U.S. then sought to cover up human rights abuses.

Many of these child soldiers fled to the U.S. and became involved in gangs, forming Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, a focal point in Trump’s fear-mongering campaign on immigration. When later deported, these immigrants became engaged in criminal activities, fueling the rise of MS-13 and gangs in El Salvador.

Whom Do You Believe?

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen contends that TPS is supposed to be temporary and the program should end because conditions have improved for many of the affected countries. She suggests the quality of life in places like El Salvador is better.

Immigrants from TPS countries tell a different story.

Erika witnessed firsthand how the conditions have worsened in the region when she returned to El Salvador three years ago—her first time in her native country since she was 7.

“As soon as I got to the place where I grew up in, the gangs already knew I was there,” she recalls. “They hung outside my house, watched what I was wearing, where I was going.’’

Even though she was happy to be in her “homeland” and see her father after 16 years, she was scared of the gang’s power.

Pam, a TPS holder from Nepal, came to New York in 1994 when she was 26. She had to leave her young children behind for many years. After an earthquake in 2015 ravaged her country, she received TPS. She tried to adjust her status several times by paying a lawyer thousands of dollars, with no success. She now works in New York City as a nanny.

Earlier this year, Pam was able to return to Nepal after applying for—and receiving—TPS parole to leave the country on a limited basis. She saw her now-adult children for the first time in 24 years. And she saw firsthand how dire the conditions in her home country remain.

“Lots of people are homeless still, buildings are broken and there are no jobs for people,” she explains. “There is dust everywhere from collapsed buildings and in front of houses and outside of them. Health conditions continue to worsen and people have to wear masks to breathe and often two masks.”

Irvis Orozco is public policy leader and independent journalist. A version of this story appears on the website LawAtTheMargins.com.